handbook, explanation, plot summary, and characters

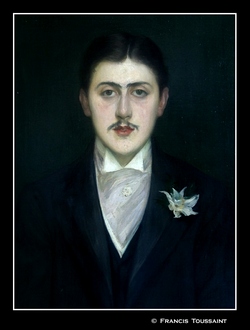

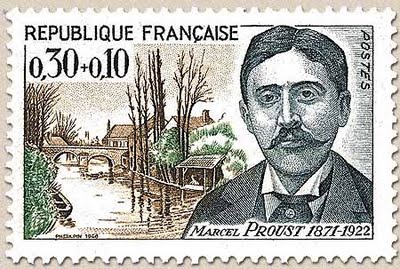

After nearly 100 years, Marcel Proust’s The Remembrance of Things Past remains as formidable a reading task as when it first appeared. Indeed, possibly more so – since it was originally published in single volumes at intervals, which gave contemporary readers a chance to digest its contents slowly. But it now exists in seven volumes totalling 3,200 pages, a million and a half words, and containing more than 400 characters.

This is not an intellectual journey to be undertaken lightly, and even experienced readers need all the help they can get to deal with a literary construction of this magnitude. Patrick Alexander’s guide is an attempt to provide all the assistance that’s required. The book is in three parts. The first offers an overview then a summary of what takes place in each of the seven volumes of the novel. Part two is a who’s who – thumbnail sketches of the principal characters, what they do, and to whom they are related.

This is not an intellectual journey to be undertaken lightly, and even experienced readers need all the help they can get to deal with a literary construction of this magnitude. Patrick Alexander’s guide is an attempt to provide all the assistance that’s required. The book is in three parts. The first offers an overview then a summary of what takes place in each of the seven volumes of the novel. Part two is a who’s who – thumbnail sketches of the principal characters, what they do, and to whom they are related.

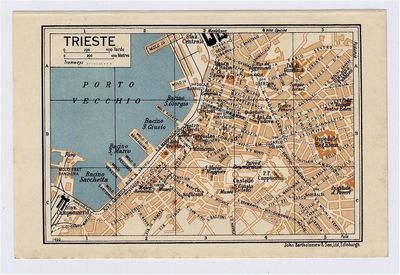

Part three offers a brief account of Proust’s life, notes on Paris and the Belle Epoque, and brief essays on French history and the notorious Dreyfus affair in particular.

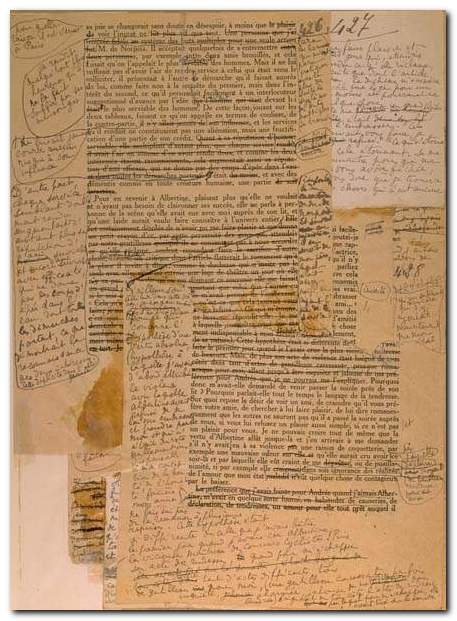

During the course of his paraphrase, Alexander examines the ‘epiphanies’ for which Proust is famous; he shows the links between characters and events spanning the whole of the seven volumes which will not be apparent to a first-time reader; and he looks at Proust’s techniques of detailed and protracted analysis which, to anyone who has paid close enough attention, are not simply analyses but highly imaginative and extended metaphors which demonstrate his intellectual skill for seeing similarities between apparently disparate objects.

As Alexander points out, Proust’s novel is also an amazing cultural encyclopedia. Whilst the narrative explores issues of love, friendship, jealousy, memory and time, it is also packed with cultural references:

His literary references range from Xenophon to (then) contemporary novelists such as Zola; his musical references cover western music from Palestrina to Puccini, and he refers to more than one hundred individual painters from Botticelli to the avant garde Léon Bakst. All of these references are used to express and illustrate startlingly original insights into every aspect of the human condition, from love and sex to religion and death – and all with a freshness and comic sense of the absurd.

It is often observed by those who have read Proust that so powerful are the evocations of place and the recreation of his life experiences, that readers afterwards find it difficult to believe that they are not their own. “Yes – That’s exactly how it is!” sums up this sort of reaction, though of course it is his genius to have put it into words in the first place.

And for a writer so renowned for prolixity (even longeurs) what is not so frequently observed is the fact that he is much given to placing pithy aphorisms in his text, deeply embedded in huge paragraphs though they might often be.

This book should appeal to the intelligent ‘Common Reader’ who wants to undertake the extended literary journey that a reading of Proust presents. And it will be a reliable guide mainly because it was written by exactly such a person, composed as a homage to a writer he had come to love.

© Roy Johnson 2009

Patrick Alexander, Marcel Proust’s Search for Lost Time: A Reader’s Guide to The Remembrance of Things Past, New York: Vintage, 2009, pp.3391, ISBN 0307472329

More on Marcel Proust

Twentieth century literature

More on biography

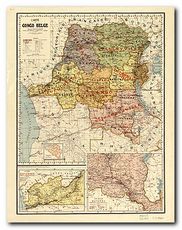

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes

The Cambridge Companion to Proust

The Cambridge Companion to Proust Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust

1882. James Joyce was born in Dublin, the eldest of ten children. His father was a rather improvident tax collector. The family became progressively impoverished.

1882. James Joyce was born in Dublin, the eldest of ten children. His father was a rather improvident tax collector. The family became progressively impoverished. James Joyce

James Joyce The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book, London: Routledge, 1996.

Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book, London: Routledge, 1996. The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism. Dubliners is his first major work – a ground-breaking collection of short stories in which he strips away all the decorations and flourishes of late Victorian prose style. What remains is a sparse yet lyrical exposure of small moments of revelation – which he called ‘epiphanies’. Like other modernists, such as Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, Joyce minimised the dramatic element of the short story in favour of symbolic meaning and a more static aesthetic. This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century. The collection ends with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. It caused controversy when it first appeared, and was the first of many of Joyce’s works to be banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories. New readers should start here.

Dubliners is his first major work – a ground-breaking collection of short stories in which he strips away all the decorations and flourishes of late Victorian prose style. What remains is a sparse yet lyrical exposure of small moments of revelation – which he called ‘epiphanies’. Like other modernists, such as Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, Joyce minimised the dramatic element of the short story in favour of symbolic meaning and a more static aesthetic. This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century. The collection ends with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. It caused controversy when it first appeared, and was the first of many of Joyce’s works to be banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories. New readers should start here. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return. Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day. Finnegans Wake is famous in literary circles as a great novel which almost no one has ever read. Joyce said that he spent seventeen years of his life writing Finnegans Wake and that he expected readers to spend the rest of their lives trying to understand it. It continues where Ulysses leaves off in terms of linguistic complexity. Written and rewritten many times over, Joyce eventually decided to incorporate many languages other than English into the narrative. It is a fantastic crossword-puzzle of puns, parodies, jokes and linguistic invention which make enormous intellectual demands on the reader. This, in addition to the many arcane references and a very complex narrative make Finnegans Wake a literary experiment which has never been surpassed. It is one of the great unread masterpieces of twentieth century literature.

Finnegans Wake is famous in literary circles as a great novel which almost no one has ever read. Joyce said that he spent seventeen years of his life writing Finnegans Wake and that he expected readers to spend the rest of their lives trying to understand it. It continues where Ulysses leaves off in terms of linguistic complexity. Written and rewritten many times over, Joyce eventually decided to incorporate many languages other than English into the narrative. It is a fantastic crossword-puzzle of puns, parodies, jokes and linguistic invention which make enormous intellectual demands on the reader. This, in addition to the many arcane references and a very complex narrative make Finnegans Wake a literary experiment which has never been surpassed. It is one of the great unread masterpieces of twentieth century literature.