socialite, rebel, poet, publisher, activist

Nancy Cunard (1896-1965) was heiress to the Anglo-American Cunard shipping line. She was a glamorous and notorious figure in fashionable society of the 1920s and 1930s in both London and Paris. She flouted convention by taking multiple lovers, including in particular one black American jazz pianist. She also espoused left wing causes, was close to the Communist Party, supported anti-racist movements, and ran her own publishing company which produced the works of modern poets.

She was born in 1896 at Neville Holt in Leicestershire, a country house that dates back to the thirteenth century. Her family were super-rich anglicised Americans, owners of the Cunard shipping company. Her father pursued a traditional country gentleman lifestyle, with a favourite hobby of metalwork. Her mother hated the countryside, and covered the Tudor oak panelling of her husband’s walls with white paint.

Nancy’s childhood was typical for the upper class – forty servants in the house and her parents completely absent. When her mother was at home she filled the house with musicians and writers, including the Irish novelist George Moore, who it was thought might have been Nancy’s genetic father. Nancy had a precocious taste in literature and read widely in English and French.

In 1910 her mother began an affair with the conductor Thomas Beecham, left her husband, and moved to London, taking Nancy with her. They lived in Cavendish Square in a grand house rented from Herbert Asquith when he moved into 10 Downing Street as prime minister.

Nancy was a gifted student who finished off her education in Munich and Paris. In 1914, on the eve of war, she befriended Iris Tree and was presented at Court as a debutante. She and Iris set up their own studio in Bloomsbury, and Nancy began writing poetry. She met Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound, and became a much-admired figure at the Cafe Royal.

During the following year she suddenly got married to Sydney Fairbairn, a handsome young soldier of whom her mother disapproved. The marriage lasted twenty months, which she later described as the unhappiest of her life. Nancy went to live with Sybil Hart-Davis, who was to have a strong influence on her. She fell in love with another soldier, but he was killed in 1917.

In London she lived an aimless, dissipated life and became a regular at the Eiffel Tower in Fitzrovia where she got ‘buffy’ with various drinking companions. She began preparations to separate herself legally from her husband, then in 1920 emigrated to Paris.This marked a turning point in her life and was the start of her becoming the archetypical ‘Bright Young Thing’. She was vividly attractive, dressed well, smoked and drank to excess, and exercised her sexual independence with gusto.

Her first major conquest around this time was Michael Arlen (real name Dikran Kouyoumdjian) the Armenian writer who was to make his name shortly afterwards with his novel The Green Hat. The next of her many lovers was Aldous Huxley, though she found him physically repellent. Being in bed with him, she said, was like being crawled over by slugs.

In 1921 she published (at her own expense) her first collection of poems – Outlaws. It received favourable reviews, largely written by her friends or by her mother’s influential contacts. She moved restlessly between England, the south of France, and Venice, where she had an affair with Wyndham Lewis, which he described in distinctly unflattering terms in his own memoirs.

She made friends with the Dadaist Tristan Tzara and English travel writer Norman Douglas, and eventually set up her own flat in Paris. In 1925 she produced a long narrative poem Parallax which was published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press,

The following year the next of her amorous conquests was the French surrealist and communist Louis Aragon. His influence reinforced her natural rebelliousness and she began to espouse a number of popular left-wing causes.

When her father died he left her all his money. She bought a house in Normandy sixty miles from Paris. There she set up her own printing press which was dedicated to producing modern poetry in limited editions – though she also published some pornography.

In 1928 she met Henry Crowder in Venice. He was the pianist in an all-black American jazz band led by the violinist Eddie South. At the end of the ‘season’ she took him back to Paris, at the same time adding the English poet and novelist Richard Aldington to her roster of lovers.

She re-established the Hours Press in Paris and published her first real literary discovery – Samuel Beckett. On a trip back to London she organised a private viewing of Bunuel’s surrealist film L’Age d’Or, which at that time was considered shocking to the point of illegality.

Meanwhile Nancy’s mother Lady Cunard was incandescent with rage, having learned that her daughter had a black lover. There were all sorts of anguished racist enquiries regarding the degree of his blackness. In fact Crowder had an African-American father and a Native American mother. There was a rift between mother and daughter, and Nancy’s allowance was reduced, but she spent the rest of her life (as she had spent the first part) living off her parents’ money.

Following this rupture she paid for Crowder’s ticket back to America and went to live in Cagnes with her latest lover, the nineteen year old Raymond Michelet. In 1931 her sympathy for the black cause was fired up by the Scottsboro Boys case, and when Crowder reappeared in Europe she persuaded him to take her to America. She stayed in Harlem for a month and met figures such as Marcus Garvey, Langston Hughes, and W.E.B. Du Bois.

On return to Europe she wrote an essay Black Man and White Ladyship which was partly an apologia for what would later be known as ‘negritude’ and partly a savage attack on the racism of her mother. She had the work privately printed and sent copies to everyone she knew – including her mother’s friends. It caused a sensation and tarnished her reputation, though many would now see it as a brave and prescient work.

In 1932 she conceived the idea of publishing an anthology celebrating black culture and history called Negro (a perfectly acceptable term at that time). More trans-Atlantic crossing were made for ‘research’ and there was controversy wherever she went with the project. She was joined in this endeavour by the young English communist writer Edgell Rickword.

When the book finally appeared in 1934 it was an enormous production – 855 pages, 12″ X 10.5″ format, and two inches thick. In terms of its content, the book was fifty years ahead of its time, with contributions from writers who are now regarded as the fathers (and mothers) of black identity. Commercially it was a flop, partly because of the high cover price (two guineas) and partly because it was ignored by the left-wing press in the UK and the USA because it didn’t toe the party line. Original copies are now collectors’ items, currently retailing at just below twenty thousand Euros.

The relationship with Crowder came to yet another but this time decisive end. Nancy threw herself into politics, visited Moscow, and became a journalist for the Associated Negro Press, reporting from Geneva on the crisis in Abyssinia. When the fight against Mussolini’s aggression failed in 1936 she immediately joined the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War.

In Madrid she met the young Chilean poet (and consul) Pablo Neruda and later collaborated with him in compiling the now famous anthology Authors Take Sides on the Spanish War (1937) which was entirely her own initiative.

In 1939 she joined the thousands of Spanish refugees fleeing from Franco’s troops across the border into southern France, where the reception there was far from friendly. People were herded into a concentration camp in Argeles, from where she helped rescue a small group of intellectuals, all the time filing copy for the Manchester Guardian. Then as the lights went out all over Europe in September 1939 she escaped (as did many others, with the help of Varian Fry) to the safety of Latin America.

Her first refuge was in Santiago, Chile, then she moved on to Mexico (where Leon Trotsky found brief asylum). She dallied with relatives in the Bahamas for the next two years, then in 1941 made her way back to London, living in a borrowed flat in one of the Inns of Court. During the remainder of the war she worked in various secretarial jobs, translating and writing reports. She also produced another anthology – Poems for France. As soon as Paris was liberated in 1944 she went back to live there.

Her house at Reanville had been vandalised and looted, not only by the occupying Germans but by local villagers who resented her bohemian lifestyle. She applied for compensation but got nothing. Eventually the property was sold and she bought an old farmhouse in Souillac in the Dordogne.

Still travelling restlessly around Europe (a tax exile, only allowed three months maximum residency in Britain) she produced in the early 1950s a book on her friend Norman Douglas (omitting his paedophilia) and received news of the death in Washington of Henry Crowder. She also produced a memoir of George Moore, but failed in an attempt to generate the autobiography which everyone wanted her to write.

As she reached her sixties her health got worse, as did her public behaviour. She got into fights, was in trouble with the police in England and France, and was finally expelled from Spain after being jailed for several days in Valencia.

Back in England, she was arrested for soliciting and being drunk and disorderly in the King’s Road, remanded in Holloway for a medical report, and certified insane. She remained in a sanitorium for several months, then was released to stay with friends. As soon as her passport was returned she went back to the Dordogne.

The last years of her life were divided between the house which was deteriorating with neglect and the homes of loyal but exasperated friends in the South of France. Predictably, she argued with them and suddenly left for Paris.

There, weighing only twenty-six kilos, pumped full of drugs (after a broken leg) and fuelled by her favourite tipples of rum and cheap red wine, she fell into another seizure of near-insanity, was certified by a local doctor, and died three days later under an oxygen tent in a public ward. She was cremated and her ashes were placed in Pere Lachaise Cemetery.

© Roy Johnson 2018

Nancy Cunard – Buy the book at Amazon UK

Nancy Cunard – Buy the book at Amazon US

Ann Chisholm, Nancy Cunard, London: Penguin, 1979, pp.480, ISBN: 014005572X

More on biography

More on literary studies

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Following Sasha’s return to Russia, the desolate, lonely Orlando returns to writing The Oak Tree, a poem started and abandoned in his youth. This period of contemplating love and life leads him to appreciate the value of his ancestral stately home, which he proceeds to furnish lavishly and then plays host to the populace. Ennui sets in and a persistent suitor’s harassment leads to Orlando’s appointment by King Charles II as British ambassador to Constantinople. Orlando performs his duties well, until a night of civil unrest and murderous riots. He falls asleep for a lengthy period, resisting all efforts to rouse him.

Following Sasha’s return to Russia, the desolate, lonely Orlando returns to writing The Oak Tree, a poem started and abandoned in his youth. This period of contemplating love and life leads him to appreciate the value of his ancestral stately home, which he proceeds to furnish lavishly and then plays host to the populace. Ennui sets in and a persistent suitor’s harassment leads to Orlando’s appointment by King Charles II as British ambassador to Constantinople. Orlando performs his duties well, until a night of civil unrest and murderous riots. He falls asleep for a lengthy period, resisting all efforts to rouse him.

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse The Complete Shorter Fiction

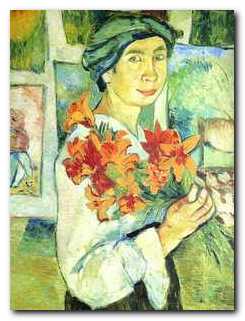

The Complete Shorter Fiction The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures. Ottoline Morrell (1873-1938) features in the history of the

Ottoline Morrell (1873-1938) features in the history of the