1903. George Orwell born as Eric Arthur Blair in Mothari, Bengal. His father was an English government official in the Opium department.

1903. George Orwell born as Eric Arthur Blair in Mothari, Bengal. His father was an English government official in the Opium department.

1904. Blair moves with mother, Ida Mabel Limouzin and older sister, to Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, to be educated in England, according to Anglo-Indian tradition.

1908. Attends Anglican convent school in Henley.

1911. Attends St Cyprian’s, a preparatory school in Eastbourne.

1917. Attends Eton as a King’s Scholar.

1921. Leaves Eaton, but does not go on to university.

1922. Joins the Indian Imperial Police and serves as an officer in Burma.

1927. Resigns from Indian Police and returns to England.

1928. Goes to Paris to become a writer.

1929. Money runs out – returns to England and becomes a tramp.

1932. Secures a job teaching in a private school.

1933. Publishes Down and Out in Paris and London using the pseudonym George Orwell.

1934. Works in a bookshop in London. Publishes his first novel – Burmese Days.

1935. Meets his future first wife, Eileen Maude O’Shaughnessy. Publishes A Clergyman’s Daughter.

1936. Visits the north of England, researching working conditions amongst miners. Marries Eileen O’Shaughnessy. Publishes Keep the Aspidistra Flying Goes to Spain and joins the POUM to fight in the Spanish Civil War.

1937. Shot through the neck and returned to England. Publishes The Road to Wigan Pier.

1938. Publishes Homage to Catalonia.

1939. Publishes Coming Up for Air.

1940. Publishes Inside the Whale

1941. Joins the BBC as a talks producer and broadcaster for India. Publishes The Lion and the Unicorn. Writes reviews for Time and Tide, Tribune, The Observer, Partisan Review, and Manchester Evening News,

1943. Resigns from the BBC and becomes literary editor of Tribune.

1944. Completes Animal Farm, but no publisher will accept it. He and Eileen adopt baby boy, Richard.

1945. Resigns from Tribune to become war correspondent for The Observer. Death of wife Eileen. Animal Farm published and becomes successful overnight.

1946. Leaves London to live with son and nurse on the island of Jura.

1947. Becomes ill and enters hospital near Glasgow.

1948. Returns to live on Jura.

1949. Enters a sanatorium in Gloucestershire. Nineteen Eighty-Four published to instant success. Admitted to University College Hospital, and marries Sonia Brownell, a former colleague from Tribune.

1950. Dies of tuberculosis and is buried in Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire. Shooting an Elephant and Other Essays.

1953. Such, Such Were the Joys

George Orwell: A Life is the more-or-less standard biography, written in 1980 and revised twice since then. Bernard Crick puts his emphasis on Orwell’s politics. There are other more recent biographies, but Crick’s will help you to understand the social and ideological background to the turbulent period through which Orwell lived and wrote. It’s particularly good for understanding the strained allegiances amongst socialists and liberals caused by the Stalinist betrayal.

George Orwell: A Life is the more-or-less standard biography, written in 1980 and revised twice since then. Bernard Crick puts his emphasis on Orwell’s politics. There are other more recent biographies, but Crick’s will help you to understand the social and ideological background to the turbulent period through which Orwell lived and wrote. It’s particularly good for understanding the strained allegiances amongst socialists and liberals caused by the Stalinist betrayal.

© Roy Johnson 2004

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987) was born in Malta, the son of an English army officer. After spending some of his childhood in South Africa and India, he grew up in an isolated Cotswold village. He studied at Radley College and then the military academy at Sandhurst. Travel and adventure were to be his way of life, and at sixteen he ran away from home. His aim was to reach Central Asia but the outbreak of the Balkan War and shortage of money caused him to return to England. He studied to enter the Indian Police (as did his near-contemporary

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987) was born in Malta, the son of an English army officer. After spending some of his childhood in South Africa and India, he grew up in an isolated Cotswold village. He studied at Radley College and then the military academy at Sandhurst. Travel and adventure were to be his way of life, and at sixteen he ran away from home. His aim was to reach Central Asia but the outbreak of the Balkan War and shortage of money caused him to return to England. He studied to enter the Indian Police (as did his near-contemporary  South from Granada

South from Granada The Spanish Labyrinth

The Spanish Labyrinth

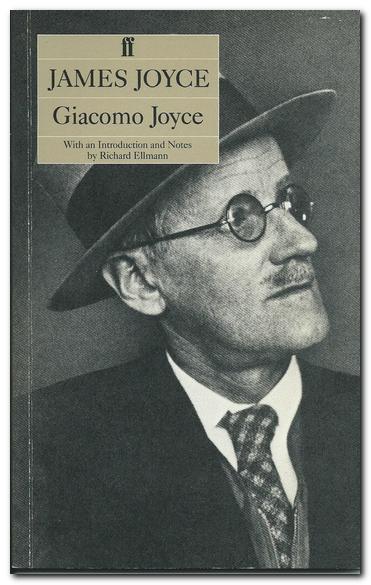

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) was born into an upper middle-class family in Tehran, where his father (Lord Carnock) was the British ambassador to Persia. as it then was. He was educated at Wellington College then Balliol College Oxford, where he graduated with a third-class degree. He entered the diplomatic service in 1908 and was posted to Constantinople where he became a specialist in Balkan affairs. In 1910 he met

Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) was born into an upper middle-class family in Tehran, where his father (Lord Carnock) was the British ambassador to Persia. as it then was. He was educated at Wellington College then Balliol College Oxford, where he graduated with a third-class degree. He entered the diplomatic service in 1908 and was posted to Constantinople where he became a specialist in Balkan affairs. In 1910 he met

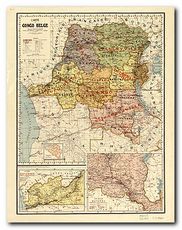

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes