a selection of web-based archives and resources

This short selection of James Joyce web links offers quick connections to resources for further study. It’s not comprehensive, and if you have any ideas for additional resources, please use the ‘Comments’ box below to make suggestions.

James Joyce – web links

![]() James Joyce at Mantex

James Joyce at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

![]() James Joyce at Project Gutenberg

James Joyce at Project Gutenberg

A limited collection of free eTexts in a variety of digital formats.

![]() James Joyce at Wikipedia

James Joyce at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of the major works, religion, music, list of biographies, and external web links.

![]() James Joyce at the Internet Movie Database

James Joyce at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, plus box office, technical credits, and quizzes.

![]() James Joyce Centre in Dublin

James Joyce Centre in Dublin

Exhibition centre, walking tours, lectures, and newsletter. The latest addition is a graphic novel version of ‘Ulysses’.

![]() The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

University of Wisconsin – digitised scans of Finnegans Wake and out-of-print studies on Joyce’s language, plus rare critical studies.

![]() An Annotated Ulysses

An Annotated Ulysses

An online version of Ulysses with hyperlinks giving explanations of obscure and classical references in the text.

![]() Cornell’s James Joyce Collection

Cornell’s James Joyce Collection

Cornell University – a collection of letters, manuscripts, and books documenting the life and work of James Joyce on exhibition in 2005. Particularly strong on Joyce’s early life.

![]() A Bibliography of Scholarship and Criticism

A Bibliography of Scholarship and Criticism

Slightly dated but still useful web-based compilation of criticism and commentary – covers Joyce himself, plus the stories and novels.

James Joyce and Samuel Beckett

Very funny short film featuring James Joyce playing pitch and put with Samuel Beckett

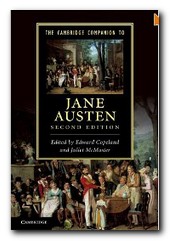

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on James Joyce

Twentieth century literature

More on study skills

David Cecil, A Portrait of Jane Austen, London: Constable, 1978.

David Cecil, A Portrait of Jane Austen, London: Constable, 1978. Jane Austen: a Life is a biography which traces Jane Austen’s progress through a difficult childhood, an unhappy love affair, her experiences as a poor relation and her decision to reject a marriage that would solve all her problems – except that of continuing as a writer. Both the woman and the novels are radically reassessed in this biography. Her life was superficially uneventful, but Claire Tomalin brings out the flesh and blood woman who lies behind the cool, ironic prose.

Jane Austen: a Life is a biography which traces Jane Austen’s progress through a difficult childhood, an unhappy love affair, her experiences as a poor relation and her decision to reject a marriage that would solve all her problems – except that of continuing as a writer. Both the woman and the novels are radically reassessed in this biography. Her life was superficially uneventful, but Claire Tomalin brings out the flesh and blood woman who lies behind the cool, ironic prose. The Complete Critical Guide to Jane Austen is a good introduction to Austen criticism and commentary. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from Walter Scott to critics of the present day. It also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist journals. It also has an interesting chapter discussing Austen on the screen. These guides are very popular.

The Complete Critical Guide to Jane Austen is a good introduction to Austen criticism and commentary. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from Walter Scott to critics of the present day. It also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist journals. It also has an interesting chapter discussing Austen on the screen. These guides are very popular. Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice Sense and Sensibility

Sense and Sensibility Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey Mansfield Park

Mansfield Park Emma

Emma Persuasion

Persuasion

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures. Maynard Keynes was born and raised in Cambridge, the seat of intellectual and political power, even more so then than now. He was also educated at Eaton – and yet his social origins were quite modest. One grandfather John Brown was an apprentice printer from Lancashire who later graduated from Owens College (Manchester University) and went on to become a preacher. The other grandfather made his fortune from cultivating dahlias and roses. His father John Neville Keynes went to University College London and then to Cambridge where he briefly became a lecturer and where he met Keynes’ mother, who was a student at Newnham Hall. However, Neville (the family used their middle names) did not feel suited to the life of a don, and became instead an administrator in the examinations board.

Maynard Keynes was born and raised in Cambridge, the seat of intellectual and political power, even more so then than now. He was also educated at Eaton – and yet his social origins were quite modest. One grandfather John Brown was an apprentice printer from Lancashire who later graduated from Owens College (Manchester University) and went on to become a preacher. The other grandfather made his fortune from cultivating dahlias and roses. His father John Neville Keynes went to University College London and then to Cambridge where he briefly became a lecturer and where he met Keynes’ mother, who was a student at Newnham Hall. However, Neville (the family used their middle names) did not feel suited to the life of a don, and became instead an administrator in the examinations board. At this point Keynes’s personal life became quite complex, with cross-connections that have since made the Bloomsbury Group famous. He was a friend and ex-lover of Lytton Strachey, who had fallen in love with his own cousin

At this point Keynes’s personal life became quite complex, with cross-connections that have since made the Bloomsbury Group famous. He was a friend and ex-lover of Lytton Strachey, who had fallen in love with his own cousin  However, this mixing with Bloomsbury also brought him personal distress. Duncan Grant started an affair with

However, this mixing with Bloomsbury also brought him personal distress. Duncan Grant started an affair with  In the early 1920s Keynes was actively involved in solving the lingering problem of post-war reparations, something in which he participated as an economist, a government advisor, and (secretly) as an unofficial diplomatist. At the same time he formed a group to take over the liberal journal Nation and Athenaeum of which he made Leonard Woolf the editor. Then, in the midst of all this, he surprised everyone by falling in love with the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, who stayed in England when Diaghilev de-camped to Monte Carlo.

In the early 1920s Keynes was actively involved in solving the lingering problem of post-war reparations, something in which he participated as an economist, a government advisor, and (secretly) as an unofficial diplomatist. At the same time he formed a group to take over the liberal journal Nation and Athenaeum of which he made Leonard Woolf the editor. Then, in the midst of all this, he surprised everyone by falling in love with the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, who stayed in England when Diaghilev de-camped to Monte Carlo.