a selection of web-based archives and resources

This short selection of Joseph Conrad web links offers quick connections to resources for further study. It’s not comprehensive, and if you have any ideas for additional resources, please use the ‘Comments’ box below to make suggestions. The university-based web sites tend to be rather old in terms of graphic design, but have the advantage of depth in terms of content.

Joseph Conrad links

![]() Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Biography, tutorials, book reviews, study guides, videos, web links.

![]() Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Brief notes introducing his major works in recommended editions.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

![]() Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary career, style, politics, and further reading.

![]() Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production notes, box office, trivia, and quizzes.

![]() Works by Joseph Conrad

Works by Joseph Conrad

Large online database of free HTML texts, digital scans, and eText versions of novels, stories, and occasional writings.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

Conradian journal, reviews. and scholarly resources.

![]() The Joseph Conrad Society of America

The Joseph Conrad Society of America

American-based – recent publications, journal, awards, conferences.

![]() Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Locate a word or phrase – in the context of the novel or story.

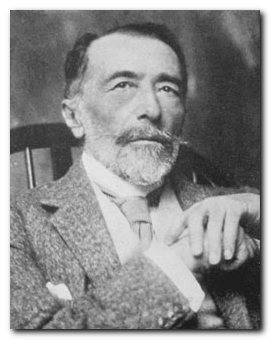

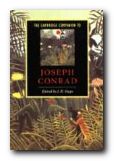

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

More on Joseph Conrad tales

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

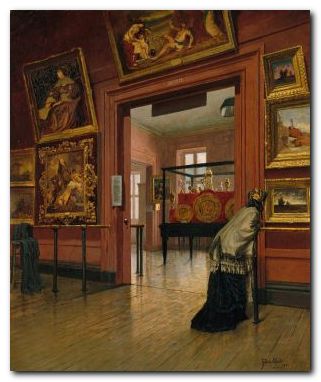

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures who had such a profound influence on the world of literature and the arts between 1900 and 1940.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures who had such a profound influence on the world of literature and the arts between 1900 and 1940.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

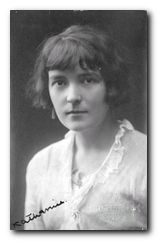

Heart of Darkness 1888. Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp was born into a socially prominent family in Wellington, New Zealand. Her father was a banker, who went on to become chairman of the Bank of New Zealand. She was first cousin of Elizabeth Beauchamp, who married into German aristocracy to become Countess Elizabeth von Arnim. She had a somewhat insecure childhood. Her mother left her when she was only one year old to go on a trip to England. She was raised largely by her grandmother, who features in some of the stories as ‘Mrs Fairfield’.

1888. Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp was born into a socially prominent family in Wellington, New Zealand. Her father was a banker, who went on to become chairman of the Bank of New Zealand. She was first cousin of Elizabeth Beauchamp, who married into German aristocracy to become Countess Elizabeth von Arnim. She had a somewhat insecure childhood. Her mother left her when she was only one year old to go on a trip to England. She was raised largely by her grandmother, who features in some of the stories as ‘Mrs Fairfield’.