1875. Thomas Mann born in Lübeck, northern Germany. His father was from a prosperous merchant family – head of the company and twice Mayor of Lübeck. His mother was artistic, with foreign blood. Five brothers and sisters. Rivalry with elder bother Heinrich, who was also a novelist. Two sisters commit suicide. Mann dislikes school, study, and discipline.

1875. Thomas Mann born in Lübeck, northern Germany. His father was from a prosperous merchant family – head of the company and twice Mayor of Lübeck. His mother was artistic, with foreign blood. Five brothers and sisters. Rivalry with elder bother Heinrich, who was also a novelist. Two sisters commit suicide. Mann dislikes school, study, and discipline.

1891. Death of father. Family moves to Munich, south Germany. [North/South = Business/Pleasure]. Brief spell working in insurance office. Mann dislikes work. One year of classes at university studying journalism.

1896. Moves to Rome and Palestrina for one year with brother Heinrich – ‘biding time’ on financial allowance.

1898. Moves back to Munich. Spends one year as editor of satirical magazine Simplicissimus. German philosophers Nietzsche and Schopenhauer early influences. Records in his diary that he is ‘close to suicide’. First stories published – Little Herr Friedmann.

1900. Starts military service, but invalided out with psycho-somatic illness after three months.

1901. Publishes Buddenbrooks, his first novel, at twenty-five. This long saga of ‘the decline of a family’ brings him instant fame.

1903. Publishes ‘Tonio Kröger’.

1905. Marries Katia, daughter of well-to-do middle-class family. They have six children. Mann has very conservative political views. Begins a novel Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man (based on memories of Manolescu) which he abandons. (He picked it up forty years later, and continued writing, exactly where he left off.)

1913. Publishes Death in Venice, a novella. Records in his diary ‘nothing is invented in Death in Venice‘.

1912. Spends three weeks in a sanatorium in Davos with his wife. Begins The Magic Mountain as a short story.

1914. Outbreak of First World War. Mann takes very conservative political line, supporting Germany. Writes essays, Reflections of an Unpolitical Man, and almost in spite of himself, his political views change. Unable to write Magic Mountain during the war.

1922. Mann’s political views become more radical in the face of rising fascism.

1924. Finishes writing The Magic Mountain.

1925. Begins a series of foreign lecture tours.

1929. Awarded Nobel prize for literature. records in his diary – ‘It lay, I suppose, upon my path in life’. Starts work on Joseph and His Brothers

1930. Mario and the Magician – short novel symbolising the rise of fascism. begins lecture tours in America.

1933. Hitler seizes power in Germany. Mann moves to Zurich. Begins political debates with fellow emigrées on how best to combat fascism and maintain the humane basis of traditional German culture.

1936. Mann’s son Klaus, a writer and theatre critic, publishes Mephisto, a novel dealing with the relationship between art and politics, the dangers of compromising with evil, and which uses the Faust theme – all of which prefigure Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus.

1938. Moves to Princeton (USA) – then to California, joining fellow emigrés Bertolt Brecht, Arnold Schoenberg, Walter Adorno, Bruno Walter, and Igor Stravinski.

1943. Begins writing Doktor Faustus.

1944. Becomes a US citizen.

1947. Doktor Faustus

1949. Suicide of Mann’s son Klaus from drug overdose.

1952. Mann returns to Europe, but refuses to choose between the divided Germanies. Settles in Zurich

1955. Dies, leaving Felix Krull unfinished.

Thomas Mann: a life This exploration of Thomas Mann’s life by Donald Prater describes his relationship of intense rivalry with his brother Heinrich, who was also a novelist, his (much-concealed) homosexuality, his career as a prolific essayist, and the vast achievement of his novels. Particular attention is paid to Mann’s opposition to Nazism, and his role in the rise and fall of Hitlerism. It traces Mann’s political development from the nationalistic conservatism of his younger days, to the humanistic anti-Nazim of his maturity.

Thomas Mann: a life This exploration of Thomas Mann’s life by Donald Prater describes his relationship of intense rivalry with his brother Heinrich, who was also a novelist, his (much-concealed) homosexuality, his career as a prolific essayist, and the vast achievement of his novels. Particular attention is paid to Mann’s opposition to Nazism, and his role in the rise and fall of Hitlerism. It traces Mann’s political development from the nationalistic conservatism of his younger days, to the humanistic anti-Nazim of his maturity. ![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

© Roy Johnson 2004

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Nostromo

Nostromo The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent

Jacob’s Room

Jacob’s Room Mrs Dalloway

Mrs Dalloway

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

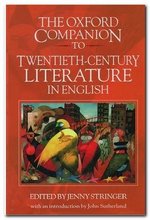

Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Literature in English

Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Literature in English Twentieth-century Britain

Twentieth-century Britain