tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

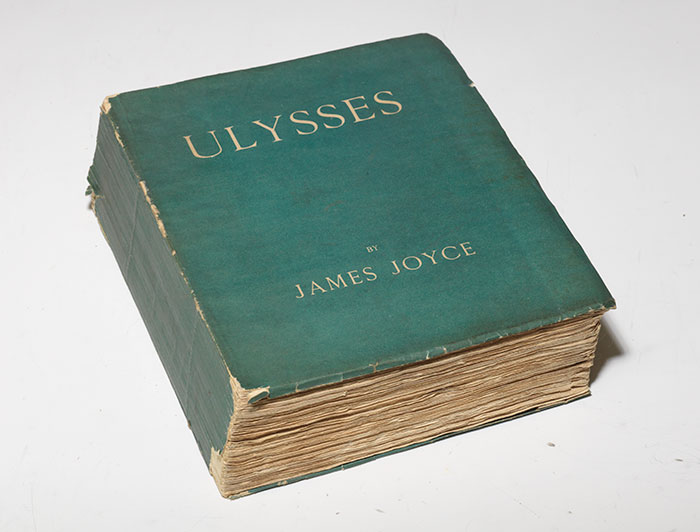

Sir Edmund Orme (1891) is one of James’s ghost stories, a literary genre which was very popular towards the end of the nineteenth century. It first appeared in the Christmas edition of the magazine Black and White and features a variation of the supernatural tale in which the ‘ghost’ is only visible to certain people. And although the story contains a suicide and two sudden deaths, the ghost actually appears to have a benign, protective purpose. It is presented as almost a ‘friendly’ ghost.

Brighton – 19th century

Sir Edmund Orme – critical commentary

The framed narrative

The story is presented to us by an un-named outer narrator who has come across a written account of events. These have been written by the inner narrator who is also the principal male figure in the story, and is also un-named.

This is a device James used a number of times – most notably in The Turn of the Screw, and like that more famous novella, the story in not in fact fully ‘framed’. That is, we are given an account of the origin of a text, but the story finishes at the end of that text. We do not go back to rejoin the introduction in any meaningful way.

The outer narrator also admits that he has no proof that the events described actually took place. The author of the text, which has been kept in a locked drawer, has written the account for his own purposes. This leaves scope for ambiguities within the tale – as well as for a variety of possible interpretations.

The ghostly element

We normally expect ghosts to be sinister and threatening. They usually appear at night, dawn, or dusk, and have a disreputable appearance and a malevolent purpose. But Sir Edmund Orme appears in broad daylight, in very public places (Brighton seafront, Tranton church) and he is well dressed and behaves with impeccable reserve.

In fact we learn, first from Mr Marden and then from the narrator’s surmise, that Sir Edmund has a protective function. He appears to Mrs Marden as an uncomfortable reminder of her previous cruelty in jilting Sir Edmund in favour of Captain Marden, but he is acting to prevent any repetition of such behaviour by her daughter. The narrator’s analysis is based on the egotistical supposition that he is being protected:

It was a case of retributive justice … The wretched mother was to pay, in suffering, for the suffering she had inflicted, and as the disposition to trifle with an honest man’s just expectations might crop up again, to my detriment, in the child, the latter young person was to be studied and watched, so that she might be made to suffer should she do an equal wrong.

However, it is open for us to observe that the net result of the narrative is the death of two women. First the fifty-five year old Mrs Marden dies on the occasion of the ghost’s last appearance, and second her daughter is dead within a year of marrying the narrator.

This reading of the text is informed by the observation that many of James’s fictions have a fear of women and marriage deeply buried within their concerns. The inner narrator befriends both Mrs Marden and her daughter, but he immediately observes that “One often hears mature mothers spoken of as warnings—sign-posts, more or less discouraging, of the way daughters may go.” And this is followed by a view of himself as a potential target for husband seekers, even though it is expressed as a negative:

I never suspected her of the vulgar purpose of ‘making up’ to me—a suspicion of course unduly frequent in conceited young men. It never struck me that she wanted me for her daughter, nor yet, like some unnatural mammas, for herself.

In other words, women are seen as threats to a bachelor’s independence and freedom from any emotional claims, and ultimately, despite any sympthy their creators show for their female concerns, they will be punished – in the same way as Emma Bovary, Anna Karenina, and Tess of the d’Urbervilles. The phenomenon was not new, even at the end of the nineteenth century.

Sir Edmund Orme – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() Sir Edmund Orme – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

Sir Edmund Orme – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() Sir Edmund Orme – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

Sir Edmund Orme – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() Sir Edmund Orme – Kindle edition

Sir Edmund Orme – Kindle edition

![]() The Ghost Stories of Henry James – Wordsworth edition

The Ghost Stories of Henry James – Wordsworth edition

![]() Sir Edmund Orme – read the book on line

Sir Edmund Orme – read the book on line

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Late Victorian Gothic Tales – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

Late Victorian Gothic Tales – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

Sir Edmund Orme – plot summary

An un-named narrator is friendly with a widow Mrs Marden and her attractive daughter in Brighton. When he begins to sense the power of his attraction to the younger woman, her mother starts to behave in an erratic manner. She wishes to promote her daughter’s relationship with the narrator, but cannot conceal her unease – and for reasons which remain mysterious.

When they meet again at a country house, the narrator accompanies Charlotte to church, where they are joined by a young man who does not speak, and who Charlotte does not even seem to notice. Mrs Marden reveals that the man is Sir Edmund Orme, who she once jilted and who subsequently committed suicide. He has been re-appearing to her intermittently ever since, as a sort of punishment and to check that Charlotte does not behave in the same way as her mother. The narrator proposes to Charlotte, but he is turned down.

Some months later they meet again at a musical party in Brighton. The narrator proposes again to Charlotte, and at the same time Sir Edmund appears. Mrs Marden faints and has to be taken home. Next day the narrator visits them and can see ‘the shadow of death’ on Mrs Marden’s face. She urges her daughter to accept the narrator’s offer of marriage, and as Charlotte does so the figure of Sir Edmund reappears in the room for what turns out to be the last time, but Mrs Marden is dead.

Principal characters

| I | the un-named outer narrator who presents the written account |

| I | the un-named inner narrator who has written the account |

| Captain Teddy Bostock | a friend of the inner narrator |

| Miss Charlotte Marden | a pretty woman of 22 |

| Mrs Marden | her mother, a wealthy widow of fifty-five |

| Captain Marden | the man she married instead of Edmund Orme |

| Sir Edmund Orme | the young man who Mrs Marden jilted |

| Brighton | real seaside resort in southern England |

| Tranton | fictional country town in Sussex |

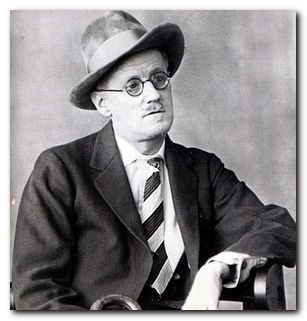

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

Ghost stories by Henry James

![]() The Romance of Certain Old Clothes (1868)

The Romance of Certain Old Clothes (1868)

![]() The Ghostly Rental (1876)

The Ghostly Rental (1876)

![]() Sir Edmund Orme (1891)

Sir Edmund Orme (1891)

![]() The Private Life (1892)

The Private Life (1892)

![]() Owen Wingrave (1892)

Owen Wingrave (1892)

![]() The Friends of the Friends (1896)

The Friends of the Friends (1896)

![]() The Turn of the Screw (1898)

The Turn of the Screw (1898)

![]() The Real Right Thing (1899)

The Real Right Thing (1899)

![]() The Third Person (1900)

The Third Person (1900)

![]() The Jolly Corner (1908)

The Jolly Corner (1908)

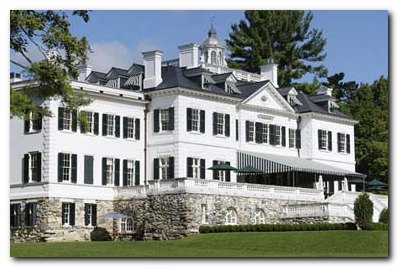

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

© Roy Johnson 2012

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Between the Acts

Between the Acts The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

Jacob’s Room

Jacob’s Room Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens