tutorial commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

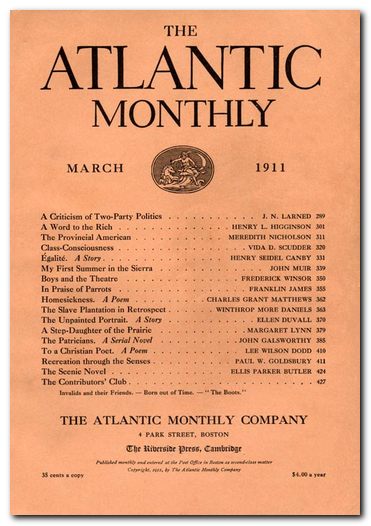

The Lesson of the Master was first published in The Universal Review for July-August 1888. It later appeared in the collection of stories which included The Marriages, The Pupil, Brooksmith, The Solution, and Sir Edmund Orme published in New York and London by Macmillan in 1892.

Lake Geneva

The Lesson of the Master – critical commentary

This is one of a number of tales which James wrote exploring the competing claims of devotion to the literary life and what would be required for marriage and family life. It should be no surprise to anybody who has read The Path of Duty, Crapy Cornelia, The Wheel of Time and A Landscape Painter that the conclusion inevitably turns out to be to remain single.

Henry St George is a successful novelist – but one who has not written anything of note for quite some time. Paul Overt, as his enthusiastic younger admirer, is hoping to learn something from him of a literary nature – but the lesson turns out to be one in life, not art.

St George warns Overt quite explicitly that marriage and the responsibilities it entails will hamper his efforts to achieve something of great artistic value. He even argues that he himself has fallen foul of the trap of worldly success. ‘I’ve had everything. In other words, I’ve missed everything.’ From a psychological point of view it is worth noting that even though his family life has been ostensibly successful, his wife prevents him from smoking and drinking.

Of course the major irony of the tale is that St George does not follow his own advice. When his wife dies, he rapidly snatches at the chance of marrying attractive and aesthetically inclined Marian Fancourt. But following the logic of his own arguments, he does not return to the altar of high art.

The second irony is that Paul Overt is deeply wounded at losing the woman he loved to the man he most admired. But he is compensated by what appears to be literary success. By choosing to remain single and exiling himself for two years’ productive work (on the shores of Lake Geneva) he thereby triumphs with a creative success.

It would therefore appear that the tale illustrates the validity of St George’s argument that the artist must sacrifice normal human relations for the sake of artistic success – as Henry James was to do himself. The artist must forego the

full, rich, masculine, human, general life, with all its responsibilities and duties and burdens and sorrows and joys – all the domestic and social initiations

At times in the story it is difficult to escape the feeling that James is talking to himself about these conflicts of interest which he explored in so many of his tales. But the weakness in the position St George takes is that his concepts of artistic success are wrapped up in so many abstract and metaphysical notions and expressed in large scale over-generalisations. He complains that he has done everything in life except

The great thing … the sense of having done the best — the sense, which is the real life of the artist and the absence of which is his death, of having drawn from his intellectual instrument the finest music that nature had hidden in it, of having played it as it should be played. He either does that or he doesn’t — and if he doesn’t he isn’t worth speaking of. And precisely those who really know don’t speak of him. He may still hear a great chatter, but what he hears most is the incorruptible silence of Fame.

Now the tale might be offered in a light-hearted spirit of fun (Leon Edel says the subject is ‘treated largely as a joke’) but it isn’t really possible to take entirely seriously an argument which is based on such ethereal suppositions. James is performing the literary equivalent of sleight of hand by appealing to this level of artistic achievement without making any effort to demonstrate its substance.

The Lesson of the Master – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() Tales of Henry James – Norton Critical Editions

Tales of Henry James – Norton Critical Editions

![]() The Lesson of the Master – Hesperus Classics

The Lesson of the Master – Hesperus Classics

![]() The Lesson of the Master – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

The Lesson of the Master – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

The Lesson of the Master – story synopsis

Part I Young author Paul Overt arrives at a country house weekend summer party hoping to meet the celebrated writer Henry St George. He is slightly shocked by his wife Mrs St George, who announces that she once made her husband burn a ‘bad’ book. Overt believes he can recognise literary and artistic ‘types’, and is surprised that St George looks so conventional. St George has also not written anything of merit for quite some time.

Part II At lunch Overt sits opposite St George, who appears to be flirting with pretty young Marian Fancourt, to whom Overt is afterwards introduced by her father. She tells him how much she admires his books and reveals that St George is critical of his own work and wishes to meet Overt whose writing he has read. They meet St George in the house, where Overt continues to persuade himself of the older man’s virtues, despite the fact that it is clear he has not read Overt’s work. There is then a walk in the park, where Overt accompanies Mrs St George, who he later learns is not in good health.

Part III After dinner Overt is joined in the smoking room by St George, who praises Overt’s writing, confesses his own declining powers, and recommends not having children. He reveals that his wife forbids him to smoke and drink. St George invites Overt to dinner at his own country house, and then they share their enthusiasm for Marian Fancourt, who St George urges him to pursue.

Part IV Overt meets Marian Fancourt at an art exhibition in London. They make further arrangements to meet, and are joined by St George, who has invited here there. St George takes her away to drive through Hyde Park, leaving Overt puzzled and a little envious. Nevertheless, next Sunday he visits Marian at home in Manchester Square , where they compare notes on St George, and Overt is so impressed by her artistic and literary appreciation that he falls in love with her. As he is leaving Manchester Square he sees St George arriving at the house. When Overt visits her again the following Sunday she tells him that St George will not be seeing her again.

Part V Overt eventually goes to dinner at St George’s house in Ennismore Gardens, after which he is invited to stay for conversation in the windowless library and study. St George once again claims that he has prostituted his own talent for financial gain, and that his wife and children are an impediment to his reaching an artistic high point. He claims that material and domestic success has prevented him from achieving his true potential. When the subject of Miss Fancourt crops up, St George argues that Overt must give her up if he wishes to be a successful writer. Overt claims that such is his wish.

Part VI Fired with enthusiasm, Overt leaves England and goes to stay on Lake Geneva to work on his next book. On receiving news of the death of Mrs St George, he is puzzled by her husband’s appreciative catalogue of her qualities and good offices. Overt thinks of returning, but stays away for two years to finish his novel. When he returns to London however, he learns that Miss Fancourt is due to marry St George. Overt feels he has been duped by both of them, but when he visits a party at Manchester Square St George claims that he has been entirely consistent in his views – and has given up writing. Overt goes home to an uncertain future, but when his book appears in the autumn it is a success.

The Lesson of the Master – characters

| I | the occasional outer narrator |

| Paul Overt | young author of Ginistrella |

| Henry St George | celebrated author of Shadowmere |

| Mrs St George | his wife |

| General Fancourt | ex India army officer |

| Marian Fancourt | his intelligent and attractive daughter |

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2014

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Kingdom of This World

The Kingdom of This World The Chase

The Chase

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times. The novel is an ironic reversal of the rags to riches story that is normally attached to immigration from the Old World to the New. Karl Rossman manages to go from riches to rags. He starts off with a wealthy and powerful uncle who showers him with luxury, but by the end of the narrative he has nothing, he is searching for work, and he is mixing with criminals and a prostitute. It is worth noting that Karl is not exactly an innocent abroad. He has been expelled from his family home following a sexual dalliance with an older servant woman that resulted in her bearing a child. So although he is only seventeen (or even fifteen) years old, Karl is in fact himself a father.

The novel is an ironic reversal of the rags to riches story that is normally attached to immigration from the Old World to the New. Karl Rossman manages to go from riches to rags. He starts off with a wealthy and powerful uncle who showers him with luxury, but by the end of the narrative he has nothing, he is searching for work, and he is mixing with criminals and a prostitute. It is worth noting that Karl is not exactly an innocent abroad. He has been expelled from his family home following a sexual dalliance with an older servant woman that resulted in her bearing a child. So although he is only seventeen (or even fifteen) years old, Karl is in fact himself a father.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis The Trial

The Trial

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Jacob’s Room

Jacob’s Room Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens