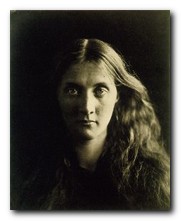

a short critical study of her life and works

The life of Virginia Woolf’s is now quite well known in its main details. Quentin Bell (her nephew) produced the definitive factual biography, and there have been interpretive studies by Lyndall Gordon, John Lehmann, Alexandra Harris, and Hermione Lee amongst others. There’s plenty of scope for writing about her life because Woolf wrote so much about herself – in letters, essays, diaries, and notebooks. She was, as Elizabeth Wright claims in this new study, possibly the most self-documented writer of the twentieth century.

Wright herself adopts a generally chronological account of the life and the works, She traces Woolf’s early upbringing in Kensington where she and her siblings produced the very amusing satirical newspaper Hyde Park Gate News. On the death of her mother at only forty-eight. Woolf experienced the first of her many mental breakdowns This was followed by the death of her half-sister Stella Duckworth, both of which events resulted in her father Leslie Stephen becoming more and more emotionally dependent on her and her elder sister Vanessa.

Wright herself adopts a generally chronological account of the life and the works, She traces Woolf’s early upbringing in Kensington where she and her siblings produced the very amusing satirical newspaper Hyde Park Gate News. On the death of her mother at only forty-eight. Woolf experienced the first of her many mental breakdowns This was followed by the death of her half-sister Stella Duckworth, both of which events resulted in her father Leslie Stephen becoming more and more emotionally dependent on her and her elder sister Vanessa.

When her father died she became an object of attentions for her half-brother George Duckworth – attentions which are now the source of much controversy. She found escape and self-expression in reading and writing, and in 1905 moved with Vanessa and her brother Thoby to 46 Gordon Square. This marked a completely new phase in her life, and she celebrated the beginnings of her independence by earning money as a reviewer for the Manchester Guardian and the Times Literary Supplement.

Once established in Bloomsbury, this was also the period of throwing off Victorian taboos – staying up late with friends discussing ideas, smoking cigarettes, using people’s first names, and even talking openly about sex. The young intellectuals who joined them for these discussions eventually became known as the Bloomsbury Group

When her sister married Clive Bell, Virginia moved with her brother Adrian to Tavistock and then Brunswick Square, and they took into their commune figures such as Leonard Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, and the painter Duncan Grant. She began work on her first novel, Melymbrosia (later to become The Voyage Out and in 1912 married her house-mate Leonard Woolf – a union that Wright tactfully describes as ‘a marriage of minds rather than bodies’.

Like most of her Bloomsbury friends Virginia was opposed the First World War: she thought patriotism a ‘base emotion’. She and Leonard bought a second-hand printing press and launched the Hogarth Press as a sort of therapeutic hobby for her. But it turned out to be a great commercial success, largely because of Leonard’s good business sense and artistic judgement. More importantly, it freed Virginia from the editorial control of commercial publishers. She could write fiction in any way she pleased, and from this point onwards her work appeared under their own imprint.

In 1921 she published her epoch-making collection of experimental short stories, Monday or Tuesday which gave her the impetus and the confidence to continue her experiments into the longer literary form of the novel with Jacob’s Room and Mrs Dalloway. Around this time she also began her love affair with fellow novelist Vita Sackville-West, which although it was short-lived gave rise to the delightful fantasy biography, Orlando.

The thirties were a period of increased fame and prosperity, tarnished only by spiteful critical attacks from the likes of Wyndham Lewis, Frank Swinnerton, and the Leavises. There was one further push in experimental modernism still to come: The Waves was her attempt to combine prose, poetry, and drama.

She turned down an invitation to deliver the Clark Lectures at Trinity College Cambridge (which her father had given in 1888) and instead directed what she had to say about these institutions of male privilege and class power into Three Guineas (1938). This was the logical development of her arguments in A Room of One’s Own and the two works now form the foundation of most modern branches of feminism.

It was certainly a productive decade. In addition to her steady stream of reviews and journalism, she produced a major critical study The Common Reader: Second Series, a long novel The Years, a play Freshwater, and even Flush, a playful biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s pet dog.

By the end of the decade there were less than two years left – yet despite her personal depressions and worries regarding the war, she continued writing and produced the ‘official’ biography of her friend Roger Fry (a thoroughly anodyne work) and left the much more spirited Between the Acts in proofs at her death.

The main strength of Elizabeth Wright’s short biography is that it strikes a good balance between the life and the works – and her account isn’t spoiled by any of the hysteria and gender bigotry which undermines so much critical commentary. After all, Virginia Woolf might have had psychological demons with which she struggled throughout her life, but she was also a prodigiously creative artist, an original analyst on some of life’s most fundamental issues, and a witty and popular figure amongst her friends.

© Roy Johnson 2012

E.H.Wright, Brief Lives: Virginia Woolf, London: Hesperus Press, 2011, pp.144, ISBN: 1843919095

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group