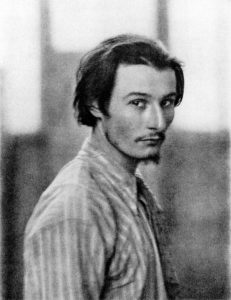

painter, designer, bohemian, bisexual

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) was an artist and bohemian who loved and was loved by both men and women. She was born Dora de Houghton Carrington in Hereford, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. As a somewhat wilful youngster, she found her family background quite stifling, adoring her father and loathing her mother. She attended Bedford High School, which emphasized sports, music, and drawing. The teachers encouraged her drawing and her parents paid for her to attend extra art classes in the afternoons. In 1910 she won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London and studied there with Henry Tonks.

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) was an artist and bohemian who loved and was loved by both men and women. She was born Dora de Houghton Carrington in Hereford, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. As a somewhat wilful youngster, she found her family background quite stifling, adoring her father and loathing her mother. She attended Bedford High School, which emphasized sports, music, and drawing. The teachers encouraged her drawing and her parents paid for her to attend extra art classes in the afternoons. In 1910 she won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London and studied there with Henry Tonks.

The Slade at that time was a centre of what we would now call radical chic. She embraced the bohemian opportunity it offered – going to live in Gordon Square in Bloomsbury, and immediately becoming entangled in romantic liaisons with fellow painters Paul and John Nash, Christopher (‘Chips’) Nevinson, and Mark Gertler, who had a very strong influence on this first phase of her life as an artist.

She also teamed up with fellow artists Dorothy Brett and Barbara Bagenal, and they started a new fashion at the school by cutting their hair into the shape of pudding-basins and wearing plain, deeply unfashionable clothes. They were called the ‘crop heads’. She did well at the Slade, winning several prizes and moving quickly through the courses. Despite her bohemianism however, her style of painting and drawing was firmly traditional, and it fitted with the aesthetic of the Slade at that time.

She was unaffected by the craze for Post-Impressionism which followed Roger Fry‘s famous 1910 exhibition at the Grafton Galleries which Virginia Woolf claimed changed human nature that year. Her personal life was dominated by the tempestuous relationship she conducted with Gertler and Nevinson which resulted in a form of unhappiness for all concerned. Although she behaved in a provocative manner, she refused to choose between them, or to have a sexual relationship with either of them.

Gertler introduced her to the society hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell, and thus into the Bloomsbury Group. In 1914 she met D.H. Lawrence and David Garnett, then joined Roger Fry’s new artists’ co-operative, the Omega Workshops, where was moderately successful in her decorative art work. It was while visiting Morrell at Garsington Manor in 1915 that Carrington made a connection that was to change the rest of her life.

Gertler introduced her to the society hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell, and thus into the Bloomsbury Group. In 1914 she met D.H. Lawrence and David Garnett, then joined Roger Fry’s new artists’ co-operative, the Omega Workshops, where was moderately successful in her decorative art work. It was while visiting Morrell at Garsington Manor in 1915 that Carrington made a connection that was to change the rest of her life.

She was introduced to the writer Lytton Strachey (who was in love with Mark Gertler at the time). Gertler felt that since Strachey was a confirmed homosexual, he could safely encourage their friendship. When Strachey made a sexual pass at her, she retaliated by going to his room at night with the intention of cutting off his long red beard. He awoke on her approach, and she immediately fell in love with him. It was a love that would last for the rest of her life and would even cause her to follow him from life into death.

Possessed of a remarkable personal fascination, she seemed to cast a spell on those around her. She figures in a number of novels, among them D.H. Lawrence‘s Women in Love (as Minette Darrington); Wyndham Lewis’ The Apes of God (as Betty Blythe); Rosamund Lehmann’s The Weather in the Streets (as Anna Corey); and Aldous Huxley’s Chrome Yellow (as Mary Bracegirdle). However, Carrington’s behaviour was viewed rather critically by another regular visitor to Garsington – D.H.Lawrence:

“She was always hating men, hating all active maleness in a man. She wanted passive maleness.”

She was not well known as a painter during her lifetime as she painted only for her own pleasure, did not sign her works, and rarely exhibited them. She painted and made woodcuts for the Hogarth Press, which was founded by Leonard Woolf as a therapeutic exercise for his wife Virginia.

Although she had kept Gertler at bay for five years, she gave herself to Strachey from the outset – then ended up having a sexual relationship with both men at the same time, even though Strachey was really a homosexual. But in 1917 Carrington ended her relationship with Gertler, and went to live with Strachey in a rented mill house.

Although she had kept Gertler at bay for five years, she gave herself to Strachey from the outset – then ended up having a sexual relationship with both men at the same time, even though Strachey was really a homosexual. But in 1917 Carrington ended her relationship with Gertler, and went to live with Strachey in a rented mill house.

Carrington’s father died in 1918 leaving her a small inheritance that allowed her to feel more independent. The following year she met Ralph Partridge, an Oxford friend of her younger brother Noel, who assisted Leonard Woolf at the Hogarth Press. Both Carrington and Lytton Strachey fell in love with Partridge, who accepted that she would not give up her platonic relationship or living arrangements with Strachey. She married Partridge in 1921, and Strachey with characteristic generosity paid for their wedding. All three of them went on the honeymoon to Venice. Strachey wrily observed:

“everything is at sixes and sevens – ladies in love with buggers and buggers in love with womanisers, and the price of coal going up too. Where will it all end?”

However, this somewhat unusual domestic arrangement seemed to work for all three parties. Carrington divided her time between looking after Strachey and her own art work. She painted on almost any medium she could find including glass, tiles, pub signs, and the walls of friends’ homes. Meanwhile, she had an affair with Gerald Brenan, who was an old army friend of Ralph Partridge.

Brenan had moved to southern Spain, where the three of them visited him (a visit he describes in South from Granada). Following this she developed a lengthy correspondence with him. The affair lasted for years, and it was painful for both of them – particularly Brenan. In 1923 she met Henrietta Bingham, the daughter of the American Ambassador to the Court of St. James. Carrington actively pursued Henrietta and they subsequently became lovers. The relationship was also another ménage à trois, since Henrietta had previously been Strachey’s lover.

The following year Strachey purchased the lease to Ham Spray House near Hungerford in Wiltshire. Carrington, Strachey, and Partridge lived there from 1924 until 1932. Her role there was to take care of the domestic chores, care for Strachey, and decorate the house. Her decision is ironic given her early rebellion against traditional roles for women in her day.

The decision might have also robbed her of time for her own art, though by her own account she was only happy when domestically settled. During 1925, Carrington met Julia Strachey, Lytton’s niece and a novelist who had once been a Parisian model and an art student at the Slade. Julia frequently visited Ham Spray, and though she was married to Stephen Tomlin, she briefly became another of Carrington’s lovers.

In 1926 Ralph Partridge started an affair with Frances Marshall, and went to live with her in London. This more or less (but not formally) ended his marriage to Carrington, although he continued to visit her most weekends.

In 1928 Carrington met Bernard (‘Beakus’) Penrose, a friend of Partridge’s and the younger brother of the artist Roland Penrose. She experienced renewed creativity while she had an affair with him, and collaborated with him on the making of three films. However, he wanted Carrington to make an exclusive commitment to him, a demand she refused because she could not end her relationship with Strachey. The affair, her last one with a man, ended badly when Carrington became pregnant and chose to have an abortion.

In November 1931 Strachey became violently ill and in late December he took a turn for the worse. Doctors were unable to correctly diagnose the problem, and in fact he had stomach cancer. Carrington attempted suicide by shutting herself in the garage with the car running, but Partridge rescued her and she recovered enough to spend the last few days of Strachey’s life taking her turn nursing him.

He died in January after seventeen years of living with her. She became depressed, borrowed a gun from a neighbour, and shot herself. She was found before she died and Ralph Partridge, Frances Marshall, and David Garnett arrived at Ham Spray House in time to say good-bye. She was just short of her thirty-ninth birthday.

Bloomsbury Group – web links

![]() Hogarth Press first editions

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, featuring designs by Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and others.

![]() The Omega Workshops

The Omega Workshops

A brief history of Roger Fry’s experimental Omega Workshops, which had a lasting influence on interior design in post First World War Britain.

![]() The Bloomsbury Group and War

The Bloomsbury Group and War

An essay on the largely pacifist and internationalist stance taken by Bloomsbury Group members towards the First World War.

![]() Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Mini web site featuring photos, paintings, a timeline, sub-sections on the Omega Workshops, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant, and biographical notes.

![]() Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Exhibition of paintings, designs, and ceramics at Toronto University featuring Hogarth Press, Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Quentin Bell, and Stephen Tomlin.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

A rich enthusiast site featuring news of events, exhibitions, new book reviews, relevant links, study resources, and anything related to Bloomsbury and Virginia Woolf

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search the texts of all Woolf’s major works, and track down phrases, quotes, and even individual words in their original context.

![]() A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

An annotated description of Clarissa Dalloway’s walk from Westminster to Regent’s Park, with historical updates and a bibliography.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Annotated tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury, including Gordon Square, University College, Bedford Square, Doughty Street, and Tavistock Square.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

News of events, regular bulletins, study materials, publications, and related links. Largely the work of Virginia Woolf specialist Stuart N. Clarke.

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

A charming sound recording of a BBC radio talk broadcast in 1937 – accompanied by a slideshow of photographs of Virginia Woolf.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephens’ collection of family photographs which became known as the Mausoleum Book, collected at Smith College – Massachusetts.

![]() Bloomsbury at Duke University

Bloomsbury at Duke University

A collection of book jacket covers, Fry’s Twelve Woodcuts, Strachey’s ‘Elizabeth and Essex’.

© Roy Johnson 2000-2014

More on art

More on design

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

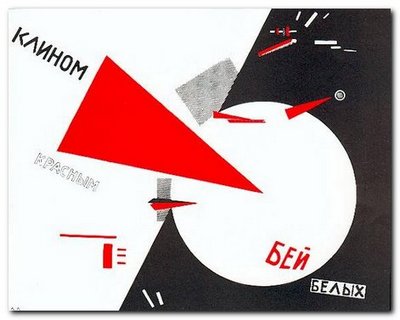

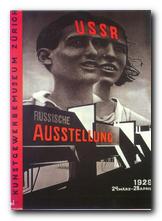

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.

But it’s amazing to realise in how short a creative lifespan artists like El Lissitzky (and Rodchenko) had when they exerted such a powerful influence on the modernist movement. The images, paintings, typography, and ‘designs for projects’ illustrated in this collection are almost all from the 1920s. By the following decade El Lissitzky had become little more than an exhibition organiser. He was working for the State – but by the 1930s the dead hand of totalitarian control had stifled all originality from the arts, and his interesting designs for the Kremlin were replaced by the sort of drab architecture that became the norm under Stalin.