Quotation marks

![]() Quotation marks or quote marks are the single or double raised commas used at the beginning and the end of a written quotation.

Quotation marks or quote marks are the single or double raised commas used at the beginning and the end of a written quotation.

![]() Single quote marks are shown ‘thus’.

Single quote marks are shown ‘thus’.

![]() Double quote marks are shown “thus”.

Double quote marks are shown “thus”.

![]() There are a number of instances where they are used.

There are a number of instances where they are used.

![]() The simplest case to remember is that double quote marks should be reserved to show speech

The simplest case to remember is that double quote marks should be reserved to show speech

“Good gracious!” exclaimed the duchess.

![]() The next most common use is when discussing somebody else’s writing:

The next most common use is when discussing somebody else’s writing:

In his recent account of the phone hacking scandal, Guardian journalist David Pallister mentions the ‘deep-seated culture of corruption’ shared by the police and the tabloid press.

![]() The words quoted are put into single quote marks for two reasons:

The words quoted are put into single quote marks for two reasons:

- to show them distinct from the author’s own discussion

- to respect the original and avoid any charge of plagiarism

![]() Remember that when a statement is ‘opened’ with a quote mark, it must be ‘closed’ at some point. It must not be left open.

Remember that when a statement is ‘opened’ with a quote mark, it must be ‘closed’ at some point. It must not be left open.

![]() There are very few universally agreed conventions on the use of quote marks. Practice varies from one house style manual to another. The following are some general suggestions, based on current usage.

There are very few universally agreed conventions on the use of quote marks. Practice varies from one house style manual to another. The following are some general suggestions, based on current usage.

Emphasis

![]() In a detailled discussion, quote marks can be used as a form of emphasis, drawing attention to particular terms or expressions:

In a detailled discussion, quote marks can be used as a form of emphasis, drawing attention to particular terms or expressions:

Internet users have developed their own specialist language or jargon. People ‘download’ software, use ‘file transfer protocols’, and run checks to detect ‘viruses’.

![]() An acceptable alternative would be to display these terms in italics.

An acceptable alternative would be to display these terms in italics.

![]() This distinction becomes important in academic writing where it is necessary to show a difference between the titles of articles and the journals or books in which they are published:

This distinction becomes important in academic writing where it is necessary to show a difference between the titles of articles and the journals or books in which they are published:

Higham, J.R., ‘Attitudes to Urban Delinquency’ in Solomons, David, Sociological Perspectives Today, London: Macmillan, 1998.

Quotes within quotes

![]() It is sometimes necessary to include one quotation within another. In such cases, a distinction must be shown between the two items being quoted.

It is sometimes necessary to include one quotation within another. In such cases, a distinction must be shown between the two items being quoted.

The Express reported that ‘Mrs Smith claimed she was “deeply shocked” by the incident’.

![]() In this example, what Mrs Smith said is put in double quote marks (sometimes called ‘speech marks’) and the extract from the Express is shown in single quote marks.

In this example, what Mrs Smith said is put in double quote marks (sometimes called ‘speech marks’) and the extract from the Express is shown in single quote marks.

![]() It’s very important that the order and the logic of such sequences is maintained – because this can affect the integrity of what is being claimed.

It’s very important that the order and the logic of such sequences is maintained – because this can affect the integrity of what is being claimed.

![]() Care should be taken with punctuation both within and around quotation marks.

Care should be taken with punctuation both within and around quotation marks.

The Express also pointed out that ‘At the meeting, Mrs Smith asked the minister “How could we as a family defend ourself against these smears?”‘

Titles

![]() Quote marks are commonly used to indicate the titles of books, films, operas, paintings, and other well-known works of art. An alternative is to show these in italics.

Quote marks are commonly used to indicate the titles of books, films, operas, paintings, and other well-known works of art. An alternative is to show these in italics.

Charles Dickens’s novel ‘Bleak House’

Francis Ford Coppola’s film ‘Apocalypse Now!’

Benjamin Britten’s opera The Turn of the Screw

Pablo Picasso’s painting Guernica

![]() Quote marks can also be used to indicate the title of anything else which has a known existence, separate from the discussion:

Quote marks can also be used to indicate the title of anything else which has a known existence, separate from the discussion:

photographs, exhibitions, television programmes, magazines, newspapers

![]() Quote marks are not necessary when indicating the titles of organisations.

Quote marks are not necessary when indicating the titles of organisations.

Senator Jackson yesterday reported to the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Representatives.

History

![]() The quotation mark started its life as a raised comma. It was used at a time when typogrphical marks available to a printer were rather limited.

The quotation mark started its life as a raised comma. It was used at a time when typogrphical marks available to a printer were rather limited.

![]() With the advent of the typewriter, a single and a double raised stroke were added to the marks available – and are still present on most keyboards.

With the advent of the typewriter, a single and a double raised stroke were added to the marks available – and are still present on most keyboards.

![]() But typographical purists have now invented what are called ‘smart quotes’. These are single and double raised commas which are automatically arranged and inverted at the start and the end of a quotation:

But typographical purists have now invented what are called ‘smart quotes’. These are single and double raised commas which are automatically arranged and inverted at the start and the end of a quotation:

"Good gracious!" cried the duchess.

© Roy Johnson 2011

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

notes and style guide for reviewers

notes and style guide for reviewers

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic.

Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912) is a classic novella – half way between a long story and a short novel. It’s a wonderfully condensed tale of the relationship between art and life, love and death. Venice provides the background for the story of a famous German writer who departs from his usual routines, falls in love with a young boy, and gets caught up in a subtle downward spiral of indulgence. The novella is constructed on a framework of references to Greek mythology, and the unity of themes, form, and motifs are superbly realised – even though Mann wrote this when he was quite young. Later in life, Mann was to declare – ‘Nothing in Death in Venice was invented’. The story was turned into a superb film by Luchino Visconti and an opera by Benjamin Britten.

Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912) is a classic novella – half way between a long story and a short novel. It’s a wonderfully condensed tale of the relationship between art and life, love and death. Venice provides the background for the story of a famous German writer who departs from his usual routines, falls in love with a young boy, and gets caught up in a subtle downward spiral of indulgence. The novella is constructed on a framework of references to Greek mythology, and the unity of themes, form, and motifs are superbly realised – even though Mann wrote this when he was quite young. Later in life, Mann was to declare – ‘Nothing in Death in Venice was invented’. The story was turned into a superb film by Luchino Visconti and an opera by Benjamin Britten. Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd (1856) deals with a tragic incident at sea, and is based on a true occurence. It is a nautical recasting of the Fall, a parable of good and evil, a meditation on justice and political governance, and a searching portrait of three men caught in a deadly triangle. Billy is the handsome innocent, Claggart his cruel tormentor, and Captain Vere the man who must judge in the conflict between them. The narrative is variously interpreted in Biblical terms, or in terms of representations of male homosexual desire and the mechanisms of prohibition against this desire. His other great novellas Benito Cereno, The Encantadas and Bartelby the Scrivener (all in this collection) show Melville as a master of irony, point-of-view, and tone. These fables ripple out in nearly endless circles of meaning and ambiguities.

Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd (1856) deals with a tragic incident at sea, and is based on a true occurence. It is a nautical recasting of the Fall, a parable of good and evil, a meditation on justice and political governance, and a searching portrait of three men caught in a deadly triangle. Billy is the handsome innocent, Claggart his cruel tormentor, and Captain Vere the man who must judge in the conflict between them. The narrative is variously interpreted in Biblical terms, or in terms of representations of male homosexual desire and the mechanisms of prohibition against this desire. His other great novellas Benito Cereno, The Encantadas and Bartelby the Scrivener (all in this collection) show Melville as a master of irony, point-of-view, and tone. These fables ripple out in nearly endless circles of meaning and ambiguities. Artistically, the novella is often unified by the use of powerful symbols which hold together the events of the story. The novella requires a very strong sense of form – that is, the shape and essence of what makes it distinct as a literary genre. It is difficult to think of a great novella which has not been written by a great novelist (though Kate Chopin’s The Awakening might be considered an exception). Another curious feature of the novella is that it is almost always very serious. It’s equally difficult to think of a great comic novella – though Saul Bellow’s excellent Seize the Day has some lighter moments.

Artistically, the novella is often unified by the use of powerful symbols which hold together the events of the story. The novella requires a very strong sense of form – that is, the shape and essence of what makes it distinct as a literary genre. It is difficult to think of a great novella which has not been written by a great novelist (though Kate Chopin’s The Awakening might be considered an exception). Another curious feature of the novella is that it is almost always very serious. It’s equally difficult to think of a great comic novella – though Saul Bellow’s excellent Seize the Day has some lighter moments. Seize the Day (1956) focusses on one day in the life of one man, Tommy Wilhelm. A fading charmer who is now separated from his wife and his children, he has reached his day of reckoning and is scared. In his forties, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. Some people might wish to argue that this is a short novel, but it is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a novella. It is now generally regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works, even though he went on to write a number of successful and much longer novels – for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976.

Seize the Day (1956) focusses on one day in the life of one man, Tommy Wilhelm. A fading charmer who is now separated from his wife and his children, he has reached his day of reckoning and is scared. In his forties, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. Some people might wish to argue that this is a short novel, but it is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a novella. It is now generally regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works, even though he went on to write a number of successful and much longer novels – for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976. Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1897) is a classic novella, and a ghost story which defies easy interpretation. A governess in a remote country house is in charge of two children who appear to be haunted by former employees who are now supposed to be dead. But are they? The story is drenched in complexities – including the central issue of the reliability of the person who is telling the tale. This can be seen as a subtle, self-conscious exploration of the traditional haunted house theme in Victorian culture, filled with echoes of sexual and social unease. Or is it simply, “the most hopelessly evil story that we have ever read”? This collection also includes James’s other ghost stories – Sir Edmund Orme, Owen Wingrave, and The Friends of the Friends.

Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1897) is a classic novella, and a ghost story which defies easy interpretation. A governess in a remote country house is in charge of two children who appear to be haunted by former employees who are now supposed to be dead. But are they? The story is drenched in complexities – including the central issue of the reliability of the person who is telling the tale. This can be seen as a subtle, self-conscious exploration of the traditional haunted house theme in Victorian culture, filled with echoes of sexual and social unease. Or is it simply, “the most hopelessly evil story that we have ever read”? This collection also includes James’s other ghost stories – Sir Edmund Orme, Owen Wingrave, and The Friends of the Friends. The Aspern Papers (1888) also by Henry James, is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s private correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer seeks a husband for her plain niece, whereas the potential purchaser of the letters she possesses is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who wins out? Henry James keeps readers guessing until the very end. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in the outcome. This collection of stories also includes The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion which is another classic novella.

The Aspern Papers (1888) also by Henry James, is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s private correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer seeks a husband for her plain niece, whereas the potential purchaser of the letters she possesses is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who wins out? Henry James keeps readers guessing until the very end. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in the outcome. This collection of stories also includes The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion which is another classic novella. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of late nineteenth century imperialism and the colonial process. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement. It is certainly regarded as a classic of the novella form, and a high point of twentieth century literature – even though it was written at its beginning. This volume also contains the story An Outpost of Progress – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’. The differences between a story and a novella are readily apparent here if you read both texts and compare them.

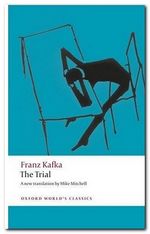

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of late nineteenth century imperialism and the colonial process. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement. It is certainly regarded as a classic of the novella form, and a high point of twentieth century literature – even though it was written at its beginning. This volume also contains the story An Outpost of Progress – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’. The differences between a story and a novella are readily apparent here if you read both texts and compare them. Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis is the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. His family are bewildered, find it difficult to deal with him, and despite the good human intentions struggling underneath his insect carapace, they eventually let him die of neglect. He eventually expires with a rotting apple lodged in his side. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s other masterly transformations of the short story form – ‘The Great Wall of China’, ‘Investigations of a Dog’, ‘The Burrow’, and the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’.

Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis is the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. His family are bewildered, find it difficult to deal with him, and despite the good human intentions struggling underneath his insect carapace, they eventually let him die of neglect. He eventually expires with a rotting apple lodged in his side. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s other masterly transformations of the short story form – ‘The Great Wall of China’, ‘Investigations of a Dog’, ‘The Burrow’, and the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’.