tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

Between the Acts was started in April 1938 and the first draft completed in November 1940 just months before Virginia Woolf died in 1941. Her husband Leonard Woolf decided to go ahead with publication in conjunction with his partner John Lehmann, editing the text only for spelling and minor errors. It had originally been called Pointz Hall and Woolf wrote it at the same time as dragging herself through the composition of the biography of her friend Roger Fry.

Virginia Woolf

Between the Acts – critical commentary

Narrative

For this, her last and posthumously published novel, Virginia Woolf returned to and developed further the narrative technique she had created for herself in Jacob’s Room in 1922. Any conventional notion of a continuous story or plot is abandoned in favour of fragmentary glimpses into the consciousness of various characters. These fragments are held together by the presentation of an aloof and rather witty narrator.

The narrative passes from one point of view to another via loosely associative threads and links, forming a pattern rather than a continuous chain. And into this pattern there are woven what Woolf herself called the ‘orts, scraps, and fragments’ which constitute human life.

The effect of continuity and apparent formlessness is intensified by the fact that Woolf abandons any formal divisions between the parts of her story: there are no chapters or any conventional breaks between the various parts of her story. You might also notice that the narration slips from the objective point of view of an author to the entirely subjective views of various characters and back again – sometimes within the same sentence.

As if to compensate for this apparently formless collection of fragments, there is a rich pattern of echoes and repetition which strengthens the construction as a whole. The characters speak and think in clichés, but the arrangement of their thoughts and utterances is like a densely patterned mosaic. Very often the dialogue echoes the narrative, and vice versa.

History

The large scale historic elements of the staged pageant are amusingly contrasted with the small scale individual drama going on amongst members of the audience. Isa is disenchanted with her husband Giles, and invents a romantic liaison with Rupert Haines the gentleman farmer, even though nothing at all happens between them except a few furtive glances. Meanwhile the angry Giles flirts with Mrs Manresa, the uninvited guest, by going off with her into the greenhouse.

There is also a recurrent theme of failed communication between the characters. People fail to remember the words of poems and songs; the actors forget their lines; other characters mis-hear what is said to them; and all in all there is sense of a failure of things to happen. The two oldest characters (Bart and his sister Cindy) mis-remember the past and fail to understand fragments of culture. Even Miss La Trobe feels that her efforts as a playwright have not been understood or appreciated by the audience.

It is true that members of the audience have entirely different interpretations of what the tableaux mean as a whole – but that is no reason that artistic creation should cease its efforts. As she consoles herself with a drink in the local pub, Miss La Trobe feels the stirrings of her next work take place in her imagination.

Between the Acts – study resources

![]() Between the Acts – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

Between the Acts – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Between the Acts – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

Between the Acts – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() Between the Acts – eBook edition

Between the Acts – eBook edition

![]() Between the Acts – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

Between the Acts – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Between the Acts – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

Between the Acts – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() Between the Acts – Kindle edition

Between the Acts – Kindle edition

![]() The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() Between the Acts – critical essays at Yale Modernism Lab.

Between the Acts – critical essays at Yale Modernism Lab.

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

Between the Acts – plot summary

On a day in June 1939 just before the outbreak of the second world war, a village historical pageant is held at Poyntz Hall, family home of the Olivers. Members of the family assemble for lunch whilst preparations for the event are made by villagers. The actions of almost all the characters are quite inconsequential, but their inner thoughts, feelings, and memories are sewn together by a narrative which creates links and patterns out of the fragments of mundane life to express a sense of community and continuity.

The pageant, written and directed by Miss La Trobe, is a series of tableaux showing periods of English history from the medieval age to the present, The first part is a prologue, recited by a child; the second is a parody of a restoration comedy; and the third is a series of scenes from Victorian life directed by a traffic policeman. At the conclusion Miss La Trobe presents a finale entitled ‘Ourselves’ by turning mirrors onto the audience.

The pageant, written and directed by Miss La Trobe, is a series of tableaux showing periods of English history from the medieval age to the present, The first part is a prologue, recited by a child; the second is a parody of a restoration comedy; and the third is a series of scenes from Victorian life directed by a traffic policeman. At the conclusion Miss La Trobe presents a finale entitled ‘Ourselves’ by turning mirrors onto the audience.

When the pageant ends, the audience disperses wondering what it all meant. Miss La Trobe initially feels that her work has failed in its effect, but then she retreats to the local pub and has an epiphany of the birth of her next creation.

The Oliver family meanwhile settle back in the house at Poyntz Hall and the day draws to a close.

Principal characters

| Bartholemew Oliver | a a retired Indian civil servant, owner of Poyntz Hall |

| Lucinda (‘Cindy’) Swithin | Oliver’s eccentric widowed sister (‘old flimsy’) |

| Giles Oliver | his son, a stockbroker with no capital |

| Isabella (‘Isa’) Oliver | Giles’ wife with unfulfilled romantic yearnings |

| Amy | a nurse at Poyntz Hall |

| Mabel | a nurse at Poyntz Hall |

| George | a young boy, Oliver’s grandson |

| Rupert Haines | a gentleman farmer |

| Mrs Haines | his wife, with protruding eyes |

| Caro | a baby |

| Sohrah | an Afghan hound |

| Mrs Sands (‘Trixie’) | cook at Poyntz Hall |

| Candish | a gardener |

| Mrs Manresa | a middle-aged bohemian vamp |

| Ralph Manresa | her husband, a Jew |

| William Dodge | a foppish and probably gay clerk |

| Miss La Trobe | a bossy lesbian author |

| Bond | a cowman |

| Albert | the village idiot |

| Eliza Clark | shopkeeper who plays Elizabeth I |

| Mabel Hopkins | plays ‘Reason’ |

| Mr Page | reporter for the local paper |

Virginia Woolf podcast

A eulogy to words

Virginia Woolf – web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

Book reviews, Bloomsbury related issues, links, study resources, news of conferences, exhibitions, and events, regularly updated.

![]() Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of her work, fiction and non-fiction publications, photograph albumns, list of biographies, and external web links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Selected eTexts of the novels The Voyage Out, Night and Day, Jacob’s Room, and the collection of stories Monday or Tuesday in a variety of digital formats.

![]() Woolf Online

Woolf Online

An electronic edition and commentary on To the Lighthouse with notes on its composition, revisions, and printing – plus relevant extracts from the diaries, essays, and letters.

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search texts of all the major novels and essays, word by word – locate quotations, references, and individual terms

![]() Virginia Woolf – a timeline in phtographs

Virginia Woolf – a timeline in phtographs

A collection of well and lesser-known photographs documenting Woolf’s life from early childhood, through youth, marriage, and fame – plus some first edition book jackets – to a soundtrack by Philip Glass. They capture her elegant appearance, the big hats, and her obsessive smoking. No captions or dates, but well worth watching.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury – including Gordon Square, Gower Street, Bedford Square, Tavistock Square, plus links to women’s history web sites.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Bulletins of events, annual lectures, society publications, and extensive links to Woolf and Bloomsbury related web sites

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

Charming sound recording of radio talk given by Virginia Woolf in 1937 – a podcast accompanied by a slideshow of photographs.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephen compiled a photograph album and wrote an epistolary memoir, known as the “Mausoleum Book,” to mourn the death of his wife, Julia, in 1895 – an archive at Smith College – Massachusetts

![]() Virginia Woolf first editions

Virginia Woolf first editions

Hogarth Press book jacket covers of the first editions of Woolf’s novels, essays, and stories – largely designed by her sister, Vanessa Bell.

![]() Virginia Woolf – on video

Virginia Woolf – on video

Biographical studies and documentary videos with comments on Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group and the social background of their times.

![]() Virginia Woolf Miscellany

Virginia Woolf Miscellany

An archive of academic journal essays 2003—2014, featuring news items, book reviews, and full length studies.

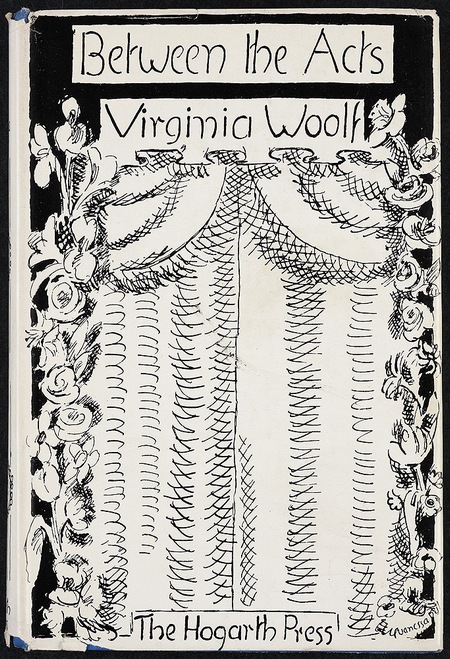

Between the Acts – first edition

Cover design by Vanessa Bell

Further reading

![]() Bell, Quentin. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Bell, Quentin. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

![]() Lee, Hermione. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Lee, Hermione. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

![]() Marsh, Nicholas. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Marsh, Nicholas. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

![]() Mepham, John. Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

Mepham, John. Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

![]() Reinhold, Natalya, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

Reinhold, Natalya, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

![]() Rosenthal, Michael. Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Rosenthal, Michael. Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

![]() Sellers, Susan, The Cambridge Companion to Vit=rginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Sellers, Susan, The Cambridge Companion to Vit=rginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

![]() Showalter, Elaine. ‘Mrs. Dalloway: Introduction’. In Virginia Woolf: Introductions to the Major Works, edited by Julia Briggs. London: Virago Press, 1994.

Showalter, Elaine. ‘Mrs. Dalloway: Introduction’. In Virginia Woolf: Introductions to the Major Works, edited by Julia Briggs. London: Virago Press, 1994.

![]() Woolf, Virginia. The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

Woolf, Virginia. The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

![]() Zwerdling, Alex. Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Zwerdling, Alex. Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Other works by Virginia Woolf

Jacob’s Room (1922) was Woolf’s first and most dramatic break with traditional narrative fiction. It was also the first of her novels she published herself, as co-founder of the Hogarth Press. This gave her for the first time the freedom to write exactly as she wished. The story is a thinly disguised portrait of her brother Thoby – as he is perceived by others, and in his dealings with two young women. The novel does not have a conventional plot, and the point of view shifts constantly and without any signals or transitions from one character to another. Woolf was creating a form of story telling in which several things are discussed at the same time, creating an impression of simultaneity, and a flow of continuity in life which was one of her most important contributions to literary modernism.

Jacob’s Room (1922) was Woolf’s first and most dramatic break with traditional narrative fiction. It was also the first of her novels she published herself, as co-founder of the Hogarth Press. This gave her for the first time the freedom to write exactly as she wished. The story is a thinly disguised portrait of her brother Thoby – as he is perceived by others, and in his dealings with two young women. The novel does not have a conventional plot, and the point of view shifts constantly and without any signals or transitions from one character to another. Woolf was creating a form of story telling in which several things are discussed at the same time, creating an impression of simultaneity, and a flow of continuity in life which was one of her most important contributions to literary modernism.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Mrs Dalloway (1925) is probably the most accessible of her great novels. A day in the life of a London society hostess is used as the structure for her experiments in multiple points of view. The themes she explores are the nature of personal identity; memory and consciousness; the passage of time; and the tensions between the forces of Life and Death. The novel abandons conventional notions of plot in favour of a mosaic of events. She gives a very lyrical response to the fundamental question, ‘What is it like to be alive?’ And her answer is a sensuous expression of metropolitan existence. The novel also features her rich expression of ‘interior monologue’ as a narrative technique, and it offers a subtle critique of society recovering in the aftermath of the first world war. This novel is now seen as a central text of English literary modernism.

Mrs Dalloway (1925) is probably the most accessible of her great novels. A day in the life of a London society hostess is used as the structure for her experiments in multiple points of view. The themes she explores are the nature of personal identity; memory and consciousness; the passage of time; and the tensions between the forces of Life and Death. The novel abandons conventional notions of plot in favour of a mosaic of events. She gives a very lyrical response to the fundamental question, ‘What is it like to be alive?’ And her answer is a sensuous expression of metropolitan existence. The novel also features her rich expression of ‘interior monologue’ as a narrative technique, and it offers a subtle critique of society recovering in the aftermath of the first world war. This novel is now seen as a central text of English literary modernism.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2013

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

Virginia Woolf – life and works

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando

Orlando Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Phyllis and Rosamond for instance introduces many of the issues she explored in her later writings – the apparently empty lives of ordinary young women who went unrecognised by history; everyday life as a subject for fiction; the inequality of the sexes; and (almost as if Jane Austen were a contemporary) the ambiguous prospect of marriage as the only possible career structure for young females.

Phyllis and Rosamond for instance introduces many of the issues she explored in her later writings – the apparently empty lives of ordinary young women who went unrecognised by history; everyday life as a subject for fiction; the inequality of the sexes; and (almost as if Jane Austen were a contemporary) the ambiguous prospect of marriage as the only possible career structure for young females.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.