cultural history – voices from the past

The Bloomsbury Group audio book is a collection of archive recordings taken from long-unheard BBC broadcasts and recordings from the Charleston Trust, many of them published here for the first time. They come in a two-CD boxed set, accompanied by a sixteen page explanatory booklet. Contributors to the Virginia Woolf Internet discussion group often comment on how astonishing it is to hear these voices from the past – and how remarkable their accents seem to us now. This is living proof that speech patterns and accents change over time.

Remember that Woolf began writing over a hundred years ago, and her father married Thackeray’s daughter – so these recordings carry with them direct links back as far as the Victorian era. For Bloomsbury Group aficionados and lovers of period nostalgia, this is a rare treat. Secondary Bloomsbury figures throw interesting light on life at that time via their first-hand accounts and memories of each other.

Remember that Woolf began writing over a hundred years ago, and her father married Thackeray’s daughter – so these recordings carry with them direct links back as far as the Victorian era. For Bloomsbury Group aficionados and lovers of period nostalgia, this is a rare treat. Secondary Bloomsbury figures throw interesting light on life at that time via their first-hand accounts and memories of each other.

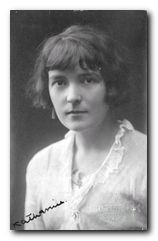

- Virginia Woolf reading an extract from a radio talk on the importance of language

- Leonard Woolf proffering a Who’s Who of the Bloomsbury Group

- Desmond McCarthy meditating on ‘tears’ in literature

- Duncan Grant discussing the infamous Dreadnought Hoax

- Clive Bell remembering Lytton Strachey asking, ‘Who would you most like to see coming up the drive?’

- Frances Partridge speaking about the Group’s larger influence

- William Plomer discussing the Group’s exclusivity

- David Garnett candidly describing the relationship between Lytton Strachey and Dora Carrington

- David Cecil detailing Virginia Woolf’s day-to-day appearance

- Angelica Garnett opining on various attitudes towards members of the Group

- Harold Nicholson reciting a talk on the members and attitudes that dominated the Group

- Vita Sackville-West talking about the inspiration behind Virginia Woolf’s Orlando

- Quentin Bell exactingly describing the fashions of Virginia Woolf

- Benedict Nicholson remembering Virginia Woolf’s visits to Sissinghurst

- Margery Fry holding court on Virginia Woolf’s flights of fancy

- Elizabeth Bowen recalling Bloomsbury parties and Virginia Woolf’s antics

- Ralph Partridge reminiscing on time spent with Leonard and Virginia Woolf

- John Lehmann describing his reactions to Woolf’s final novel, Between the Acts

- Bertrand Russell on Lytton Strachey and his family

- Gerald Brenan recalling times spent with Lytton Strachey, Ralph Partridge, and Dora Carrington

- Grace Higgins describing daily life at Charleston, the Bloomsbury outpost in Sussex

© Roy Johnson 2010

The Bloomsbury Group (Spoken Word), British Library; 2 CD audio set with 16 page booklet, edition (November 15, 2009), Language: English, ISBN: 0712305939

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

The Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group Bloomsbury Recalled

Bloomsbury Recalled Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900—1930

Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900—1930 A Bloomsbury Canvas

A Bloomsbury Canvas

Many of the book jackets were designed by Virginia’s sister, the designer and painter

Many of the book jackets were designed by Virginia’s sister, the designer and painter  Virginia Woolf is now well known for her love-affair with fellow writer

Virginia Woolf is now well known for her love-affair with fellow writer  As their enterprise became more successful and the volume of business grew, they felt they needed more help. A succession of younger men were employed to help run the Press – many of them aspirant young writers themselves. Amongst them was Richard Kennedy, a sixteen year old boy, who recorded his very amusing memories of the experience in

As their enterprise became more successful and the volume of business grew, they felt they needed more help. A succession of younger men were employed to help run the Press – many of them aspirant young writers themselves. Amongst them was Richard Kennedy, a sixteen year old boy, who recorded his very amusing memories of the experience in  Curiously enough, as John Lehmann records in his account of these years, these disasters proved to be a benefit to the press. Its editorial offices and stock rooms were in the same building as its printers, and both were a long way away from London, where other publishers were suffering losses to their inventory as a result of air raids during the war. The odd thing is that despite paper rationing, sales rose, because of general shortages: “Books that in peacetime, when there was an abundance of choice, would have sold only a few copies every month, were snapped up the moment they arrived in the shops.”

Curiously enough, as John Lehmann records in his account of these years, these disasters proved to be a benefit to the press. Its editorial offices and stock rooms were in the same building as its printers, and both were a long way away from London, where other publishers were suffering losses to their inventory as a result of air raids during the war. The odd thing is that despite paper rationing, sales rose, because of general shortages: “Books that in peacetime, when there was an abundance of choice, would have sold only a few copies every month, were snapped up the moment they arrived in the shops.” Disagreements rumbled on until after the war had ended. When the final split between them came about in 1946, Leonard solved the financial problem of raising £3,000 to keep the company afloat by persuading fellow publisher Ian Parsons of Chatto and Windus to buy out John Lehmann’s share. The Hogarth Press became a limited company within Chatto & Windus, on the strict understanding that Leonard Woolf had a controlling decision on what the Hogarth Press published.

Disagreements rumbled on until after the war had ended. When the final split between them came about in 1946, Leonard solved the financial problem of raising £3,000 to keep the company afloat by persuading fellow publisher Ian Parsons of Chatto and Windus to buy out John Lehmann’s share. The Hogarth Press became a limited company within Chatto & Windus, on the strict understanding that Leonard Woolf had a controlling decision on what the Hogarth Press published.