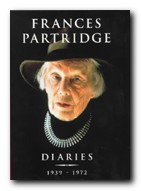

the memoirs of Frances Partridge

Beautiful, well read, and educated at Cambridge, Frances Partridge was a member of the Bloomsbury Group and until quite recently the last survivor of the group’s most famous love quadrangle. Love in Bloomsbury is a collection of her memoirs, which sketch out her childhood and adolescence, then focus on that celebrated quartet, two of whom were doomed, the other two survivors. Her story begins and ends in Bloomsbury, because she was raised in an upper middle-class Edwardian family in Bedford Square.

She was the youngest of a large family which also included her sister Ray Marshall, the painter (who later married David Garnett). They were friends of both the Stracheys and the Stephens (Virginia Woolf‘s family) and her education included school at Queen’s College, Harley Street (which Katherine Mansfield also attended) then Newnham College Cambridge, where she graduated in English and Philosophy.

She was the youngest of a large family which also included her sister Ray Marshall, the painter (who later married David Garnett). They were friends of both the Stracheys and the Stephens (Virginia Woolf‘s family) and her education included school at Queen’s College, Harley Street (which Katherine Mansfield also attended) then Newnham College Cambridge, where she graduated in English and Philosophy.

Her introduction to the Bloomsbury set was via her job at David Garnett’s bookshop. She gives a vivid account of parties, dancing, and the heady artsy-Bohemian atmosphere which flourished after the first world war. There are character sketches of all the principal Bloomsberries, Virginia Woolf, her sister Vanessa Bell, and Roger Fry, though like most of them when it came to writing their memoirs, she is extremely discreet and gives little away about the background to what were in some cases quite extraordinary liaisons.

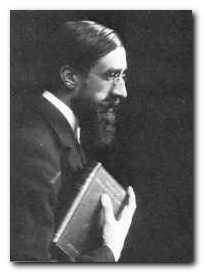

She formed a relation ship with Ralph Partridge, who was at that time married to Dora Carrington, who in her turn happened to be in love with Lytton Strachey, with whom Carrington lived – though there is no open acknowledgement of the complex sexual relationships between the principals. You would never know from this for instance that Dora Carrington had affairs with women as well as men.

Frances Partridge

There are some delightful vignettes: a long summer weekend at Charleston with Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, then a visit to Gerald Brenan‘s house in the Spanish Alpujarraras (which he describes in his classic, South from Granada).

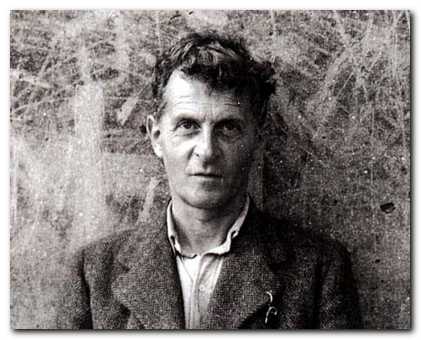

Lots of famous names flit through the pages – Arnold Bennett, Princess Bibesco, Cyril Connolly, Maurice Chevalier, and even Ludwig Wittgenstein. At one point, once her relationship with Ralph Partridge has become established (there was a rather hurried marriage) a child appears – only to disappear seven words later.

In the second part of the book her account centres on the late 1920s, reaching its climax in the death of Lytton Strachey and the subsequent suicide of Dora Carrington. After that, the narrative comes to a quiet ending, celebrating the central Bloomsbury belief that friendship ought to be cherished and celebrated.

I actually enjoyed the earlier schoolgirl and student years of her account more than the later, though her confirmation of some of the famous Bloomsberry anecdotes that one has read elsewhere does help to authenticate their veracity.

It should also be said that the writing is very stylish and poised. Frances Partridge went on to become a prolific writer in her later years, translating from French and Spanish, including work by the Cuban Nobel prizewinner Alejo Carpentier, but mainly devoting herself to her memoirs of the years which follow these.

© Roy Johnson 2000

Frances Partridge, Love in Bloomsbury, Boston: Little, Brown, 1981, pp.244, ISBN: 0316692840

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

Lytton Strachey (1880-1932) was born at Clapham Common and raised at Lancaster Gate, in central London. He was the eleventh of thirteen children, to General Sir Richard Strachey (an engineer) and his wife Jane Grant. Though he spent some years at boarding schools, including Abbotsholme and Leamington College, he received much of his education at home. His mother took an interest in literature and politics, and Strachey met many of the leading writers and thinkers of the day when they came to visit Lady Strachey. His secondary education was completed at University College in Liverpool where he studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, and English literature and history. It was there that he met and was influenced by Walter Raleigh, a professor of English literature and well known biographer.

Lytton Strachey (1880-1932) was born at Clapham Common and raised at Lancaster Gate, in central London. He was the eleventh of thirteen children, to General Sir Richard Strachey (an engineer) and his wife Jane Grant. Though he spent some years at boarding schools, including Abbotsholme and Leamington College, he received much of his education at home. His mother took an interest in literature and politics, and Strachey met many of the leading writers and thinkers of the day when they came to visit Lady Strachey. His secondary education was completed at University College in Liverpool where he studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, and English literature and history. It was there that he met and was influenced by Walter Raleigh, a professor of English literature and well known biographer.

Strachey’s Letters

Strachey’s Letters

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

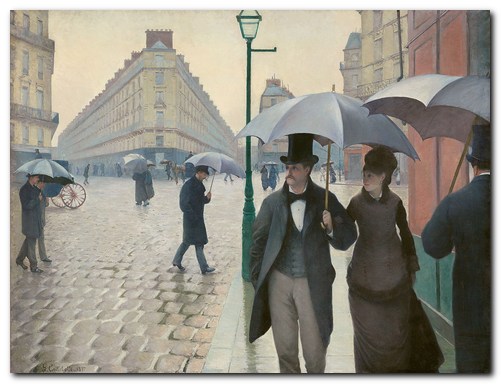

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth