tutorial, critical commentary, plot, and study resources

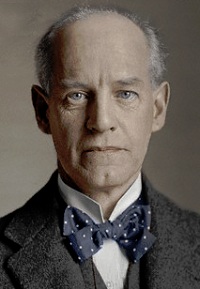

The Enchanter (1939) was one of the last works Vladimir Nabokov wrote in Russian, using his original pen name of V. Sirin. It was composed in Paris, at a time when he had just started to create works in English – the third of his childhood languages (the two others being his native Russian, and French which was the lingua franca of the Russian aristocracy). Following his arrival in America the manuscript appeared to have been lost, but it surfaced again in 1959 and was first published in English translation in 1987, ten years after the author’s death.

Because of the sensational publication of Lolita in 1955 and the scandal that ensued, The Enchanter was very obviously ripe for its own commercial success, since it dealt with the same subject – the obsession of a middle-aged man for a young girl. Yet strangely, the novella has never generated nearly as much interest with the reading public – even amongst Nabokov specialists.

The Enchanter – critical commentary

Form

Unusually for Nabokov, there is no effort made to locate the events of the story either temporally or geographically. – and none of the characters are given names, although there is a possibility (discussed by his son and translator Dmitri Nabokov in an afterward) that the protagonist’s name at one time might have been Arthur.

In terms of genre, the narrative is too long to be classified as a short story, and too short to be a novel. But the fact that its subject is concentrated so powerfully on one character and his obsession means it might justly be considered a novella.

It has the classical unities of time, place, character, and action to warrant this classification. The story is entirely concerned with the protagonist’s obsession. The other characters, even the woman he marries and the daughter he abducts, are of secondary importance. The events take place in one location, they are orchestrated in once continuous movement, and their outcome culminates in the protagonist’s tragic downfall.

Nabokov and paedophilia

In recent years, careful scrutiny of Nabokov’s work as a whole has revealed that the subject of paedophilia has been a recurring feature of his novels, from earliest to last. Consequently, there has been an embarrassed effort by some critics and editors to downplay and obfuscate the issue of a distinguished writer who had such an apparently unhealthy interest in the seduction of young girls.

For instance, the contents of this slim volume come heavily protected by double ‘explanatory’ prefaces from Nabokov himself and an afterward and running commentary by his son and translator Dmitri Nabokov. Both of these additions to the text seek to deflect attention from the uncomfortable subject of paedophilia towards the genesis and aesthetic details of the work itself.

In an afterward to Lolita (written in 1956) Nabokov claimed that the idea for its main subject had come to him from a newspaper report of a drawing produced by an ape in the Jardin des Plantes. The drawing showed the bars of its cage, the implication being that the poor beast was imprisoned both literally and metaphorically.

The protagonist of Lolita, Humbert Humbert, is a character who produces a written account of his seduction of a young girl who is his step-daughter, and his murder of a rival who also abducts and seduces her. Humbert’s written deposition (the novel) is produced from his prison cell whilst awaiting trial.

This round-about appeal to our sympathy deflects attention from two uncomfortable facts. The first is that Humbert Humbert, is not imprisoned by his obsession for under-age girls: he acts fully conscious of his desires with the free will of an adult.

The second fact is that Nabokov had been writing about older men having sexual encounters with under-age girls ever since his earliest works – such as A Nursery Tale (1926) and <Laughter in the Dark (1932). Moreover, he had already written The Enchanter (1939) which was based on that theme, and he was still including mention of what we would now class as paedophilia in works as late as Ada or Ardor (1969) and Transparent Things (1972).

Neither The Enchanter nor Lolita are isolated examples of this theme: they are merely the most explicit and fully developed examples of a topic to which Nabokov returned again and again in his work.

The Enchanter and Lolita

There is no escaping the fact that the plots of Lolita and The Enchanter are virtually identical. A middle-aged man is obsessed by young girls of a certain age – generally around twelve years old. In order to secure access to one such girl, the man marries her widowed mother and then plans to kill her. When the mother unexpectedly dies, he takes the young girl away by car to a hotel where he plans to seduce her.

Lolita herself is a far more fully developed character than the un-named girl in The Enchanter. She is more fully described and dramatised, with a quite witty line in teenage American slang.

But if The Enchanter had been published around the time it was written, Nabokov might well have been accused of self-plagiarism when Lolita appeared. It is Nabokov’s good fortune (or his skilful management of his own literary reputation) that the manuscript of The Enchanter did not emerge until three decades after the work which established his worldwide fame – and after his death in 1977.

Point of view

The whole of The Enchanter is related from the protagonist’s point of view. In fact the tale starts in first person singular narrative mode, documenting his turbulent thoughts as he tries to justify his aberrant cravings to himself:

This cannot be lechery. Coarse carnality is omnivorous; the subtle kind presupposes eventual satiation. So what if I did have five or six normal affairs—how can one compare their insipid randomness with my unique flame?

But after a few pages the narrative switches to a conventional third person mode – which is worth noting for two reasons. The first reason is technical. The story must be delivered by someone other than the protagonist if he is to die at the end of the story. (In the case of Lolita Humbert Humbert’s account of events is written whilst waiting for his trial in jail, where he dies.)

Nabokov, presenting the story in third person narrative mode, expresses the protagonist’s desires in a very sympathetic manner = almost as if they are a burden imposed upon him by forces outside himself.

having, by the age of forty, tormented himself sufficiently with his fruitless self-immolation

The protagonist’s thoughts and actions are dressed up in all the elaborate and metaphorical imagery for which Nabokov is famous, as if he wishes to obscure and intellectualise his protagonist’s desire – almost as if as an author he does not wish to address his subject directly.

The second noteworthy reason is one of persuasion. It is interesting that the articulation of the protagonist’s thoughts in the first few pages and the presentation of his acts in the remainder of the text are recounted in a remarkably similar literary style. And the style is one that regular readers of Nabokov will instantly recognise: it is the witty, elegant, and very sophisticated ‘literary’ prose he uses in most of his other works:

At daybreak he drowsily laid down his book like a dead fish folding its fin, and suddenly began berating himself: why, he demanded, did you succumb to the doldrums of despair, why didn’t you try to get a proper conversation going, and then make friends with the knitter, chocolate woman, governess, or whatever; and he pictured a jovial gentleman (whose internal organs only, for the moment, resembled his own) who could thus gain the opportunity—thanks to that very joviality— to collect you-naughty-little-girl-you onto his lap.

The reader is given every encouragement to identify and sympathise with the protagonist – which creates a moral and aesthetic problem that few people have been able to resolve in Nabokov’s work. His supporters have concentrated on the skill of his literary invention and his glossy poetic style; his detractors have pointed to his apparent lack of concern for the victims of the outrages perpetrated by his protagonists.

The Enchanter – study resources

![]() The Enchanter – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Enchanter – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Enchanter – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Enchanter – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Enchanter: An Adventure in the Land of Nabokov – Amazon UK

The Enchanter: An Adventure in the Land of Nabokov – Amazon UK

![]() The Enchanter: An Adventure in the Land of Nabokov – Amazon US

The Enchanter: An Adventure in the Land of Nabokov – Amazon US

![]() The Annotated Lolita – notes & explanations – Amazon UK

The Annotated Lolita – notes & explanations – Amazon UK

![]() The Annotated Lolita – notes & explanations – Amazon US

The Annotated Lolita – notes & explanations – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Amazon UK

![]() Zembla – the official Nabokov web site

Zembla – the official Nabokov web site

![]() The Paris Review – Interview with Vladimir Nabokov

The Paris Review – Interview with Vladimir Nabokov

![]() First editions in English – Bob Nelson’s collection

First editions in English – Bob Nelson’s collection

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

The Enchanter – plot summary

A forty year old man tries to justify his passion for young girls. His fervid thoughts swirl around memories of some earlier instances of attraction in his life.

He sees a pretty young girl roller-skating in a park, then goes back the next day to befriend the old lady who is looking after her. Following this, he arranges to visit the girl’s widowed and invalid mother on the pretext of buying some furniture.

He visits again, and they exchange information about each other – she her medical problems, he his wealth and prosperity. Despite her warnings that she might not have long to live, he eventually proposes to her.

He wants to keep the girl at home, but the mother insists on peace and quiet; she insists that the girl live with friends. On their wedding night he cannot face their nuptials, and walks the streets, planning to poison her. But he gets through the occasion, after which she reverts to being a full time invalid.

In the months that follow, her health deteriorates and she is hospitalised. He receives news that an operation has been successful, and feels outraged and disappointed. But she does die, and he makes preparations to take the girl away.

He plans to escape with her into a world of permanent sexual indulgence shielded from any influences of everyday life. He has rhapsodic visions of a love life between them which will grow with time – so long as she is not distracted by contact with other people.

He collects the girl from her minder and they go off in a chauffeur driven car, staying overnight at a hotel. After some delays with the management, he joins her in bed and explores her body whilst she is asleep.

Overcome by his desire for her, he abandons all his plans of caution and restraint, and begins to molest her. But she wakes up and screams, and this disturbance awakens other people in the hotel. He panics, escapes into the street, where he is run over and killed by a passing truck.

© Roy Johnson 2015

Vladimir Nabokov, The Enchanter, London: Penguin Classics, 2009, pp.96, ISBN: 014119118X

Vladimir Nabokov – web links

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex

Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex

Biographical notes, book reviews, tutorials, study guides, videos, web links, and essays on the Complete Short Stories.

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia

Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia

Biographical notes, list of major works, bibliography, and web links

![]() Lolita USA

Lolita USA

A ‘geographical scrutiny’ of Humbert and Lolita’s journey across America. Essay and photographic study by Dieter E. Zimmer.

![]() Vladimir Nabokov Writings – First Appearance

Vladimir Nabokov Writings – First Appearance

An illustrated collection of first editions in English. Photographs with bibliographical notes compiled by Bob Nelson

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at the Internet Movie Database

Vladimir Nabokov at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, plot, box office, trivia, continuity errors, and quiz.

![]() Zembla

Zembla

Biography, timeline, photographs, eTexts, sound clips, butterflies, literary criticism, online journal, scholarly essays, and an online annotated version of Ada – housed at Pennsylvania State University Library.

![]() Nabokov Museum

Nabokov Museum

A major collection housed in Nabokov’s old family home (now a museum) in St. Petersburg. – biography, photos, family home, videos in English and Russian.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading. ![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

More on Vladimir Nabokov

More on literary studies

Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Between the Acts

Between the Acts The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories

The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.