Adrian Mole meets Bloomsbury

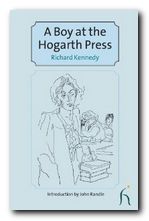

Richard Kennedy started work at the Hogarth Press when he was sixteen. He had been a complete failure at Marlborough School, and was fixed up with the job through a family connection as a special favour, starting work at one pound a week. His memoirs (and atmospheric line illustrations) were produced many years later, and they take great delight in contrasting the youth’s naive enthusiasm and his bewilderment with the sophisticated milieu into which he had been transported.

Leonard Woolf ran an enterprise in the Hogarth Press which was commercially very successful, and Kennedy joined it at a time in the 1920s when the work of Virginia Woolf (particularly Orlando) and Vita Sackville-West (All Passion Spent) were virtually best-sellers. But his approach is to depict these intellectual giants as they were seen by a sixteen year old boy. He was far more interested in learning how to chat up girls than the lofty aspirations of his employers. He contrives to present an ‘Emperor’s New Clothes’ approach to all things Bloomsbury, and the result is a sort of Adrian Mole version of events.

Leonard Woolf ran an enterprise in the Hogarth Press which was commercially very successful, and Kennedy joined it at a time in the 1920s when the work of Virginia Woolf (particularly Orlando) and Vita Sackville-West (All Passion Spent) were virtually best-sellers. But his approach is to depict these intellectual giants as they were seen by a sixteen year old boy. He was far more interested in learning how to chat up girls than the lofty aspirations of his employers. He contrives to present an ‘Emperor’s New Clothes’ approach to all things Bloomsbury, and the result is a sort of Adrian Mole version of events.

The saintly Virginia Woolf, who at that time was producing some of the most advanced texts of literary modernism, is pictured as she would appear to a young teenager:

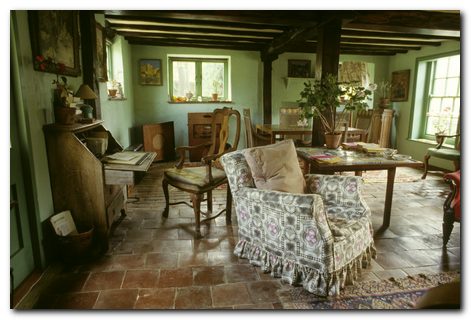

She looks at us over the top of her steel-rimmed spectacles, her grey hair hanging over her forehead and a shag cigarette (which she rolls herself) hanging from her lips. She wears a hatchet-blue overall and sits hunched in a wicker armchair with her pad on her knees and a small typewriter beside her.

His employer, the indefatigable Leonard Woolf, who ran the whole enterprise with rigorous efficiency, is cut down to size in a similar fashion:

After lunch we all straggled home over the Downs. LW stopped to have a pee in a very casual way without attempting any sort of cover. I could see that this was a part of his super-rational way of living.

But for all the naive self deprecation, you know that Kennedy is well connected. He is in fact from the same social milieu as the people he describes, as he reveals in a throwaway remark on a visit to St Ives::

The picnic over, we returned to Talland House – curiously enough, the scene of Virginia Woolf’s first successful novel, To the Lighthouse. Her parents had rented the house from my aunt’s parents .

The book is decorated by spidery but very evocative drawings which capture the mood of the era and the spirit of the text. Amazingly, they were drawn from memory in the 1970s, yet capture both the period and the principal characters very well.

It’s a slight book to say the least, but it’s very amusing and it throws light onto the workings of what was a very successful publishing business – and for Bloomsbury Group enthusiasts it has some delicious thumbnail sketches of the principals, as well as even floor plans of the rooms at the Hogarth Press, showing who was cooped up where. Full marks to Hesperus Press for bringing this delightful book back into print.

© Roy Johnson 2011

Richard Kennedy, A Boy at the Hogarth Press, London: Hesperus Press, 2011, pp.90, ISBN 1843914611

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on biography

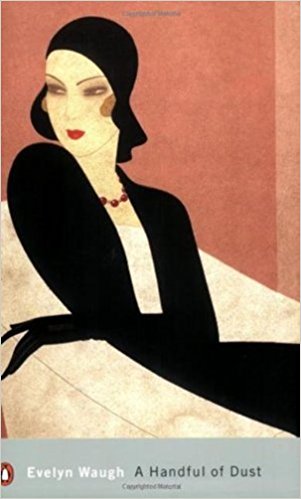

Evelyn herself writes letters packed with vacuous cliches which confirm her as a conventional upper class snob. Meanwhile, the proprietor’s cousin Mr Verdier lives there amongst them free of charge in exchange for making conversation with the guests. His letters to a friend are full of pompous and smutty innuendo concerning his flirtations with the ladies in the house.

Evelyn herself writes letters packed with vacuous cliches which confirm her as a conventional upper class snob. Meanwhile, the proprietor’s cousin Mr Verdier lives there amongst them free of charge in exchange for making conversation with the guests. His letters to a friend are full of pompous and smutty innuendo concerning his flirtations with the ladies in the house.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers

To the Lighthouse

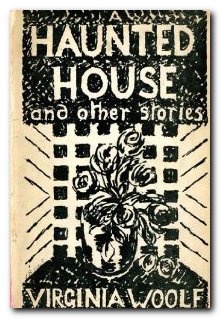

To the Lighthouse The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf