the life of a revolutionary and a great novelist

Victor Serge (1890—1947) was one of the most talented writers and intellectual historians of the early twentieth century, and yet his work still seems to be unknown outside a small group of left-wing enthusiasts. His output was colossal — novels, histories, biography, literary criticism, documentaries, journalism, poetry, and diaries — and yet he wrote under incredibly difficult conditions – often in exile or in jail, and most of the time poor and hungry. He was also an active revolutionary – which is possibly why he doesn’t sit easily within the western literary mainstream. His accounts of the reign of terror unleashed by Stalin in the 1930s anticipate later work such as Koestler’s Darkness at Noon (1940) and Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) , and offer a far more insightful explanation of the forces that were at work.

So far the majority of the information we have about his life history comes from his own magnificent Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1941) written towards the end of his life when he was an exile in Mexico. This offers a breathtaking political journey through the first four decades of the twentieth century, with Serge active in many of its key events – except that he spent most of the first world war in a French jail. But immediately on release he joined forces with insurgents, first in Barcelona, then he travelled to his spiritual homeland of Russia to join the Bolshevik revolution. Although he had been born in Belgium, his father was a Russian left-wing exile. Serge was a talented writer, translator, editor, and activist. He joined forces with the Bolsheviks, and although he had no ambitions for personal advancement, he was given important roles in the new government which enabled him to witness the mechanisms of power close up, at first hand.

So far the majority of the information we have about his life history comes from his own magnificent Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1941) written towards the end of his life when he was an exile in Mexico. This offers a breathtaking political journey through the first four decades of the twentieth century, with Serge active in many of its key events – except that he spent most of the first world war in a French jail. But immediately on release he joined forces with insurgents, first in Barcelona, then he travelled to his spiritual homeland of Russia to join the Bolshevik revolution. Although he had been born in Belgium, his father was a Russian left-wing exile. Serge was a talented writer, translator, editor, and activist. He joined forces with the Bolsheviks, and although he had no ambitions for personal advancement, he was given important roles in the new government which enabled him to witness the mechanisms of power close up, at first hand.

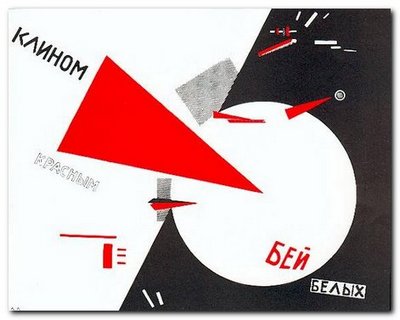

Although he arrived a year after the revolution had taken place, he quickly became engaged in its essential issues, and since he took a stance to the Left of the mainstream, he had to work a difficult path for himself. Disillusioned with official policy after the crushing of the Kronstadt rebellion, Serge accepted a posting to Berlin as an agent of the Comintern. When the Berlin revolution of 1923 was aborted – all wholly directed from Moscow – Serge moved on to Vienna and lived there for the next two years. During this period he turned his attention to literature, for as Susan Weissman observes in this huge and detailed examination of his political life, ‘Serge was first and foremost a political animal, and it was only when barred from political action that he turned to literary activity’.

In Vienna he began writing his first novel Men in Prison, which was based on his experiences of being jailed in France after being sentenced for his (tangential) part in the notorious anarchist Bonnot gang raids, and he also produced the series of articles later collected in Literature and Revolution which examined the relationship between culture and social class.

But in 1925, alarmed by the stranglehold Stalin was imposing on the Party, he returned to the Soviet Union to support the Left Opposition, which was headed by his friend Leon Trotsky. Serge could easily have stayed comfortably in western Europe, and his motives for returning to Russia – to support the revolution – were noble, but if ever there was a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, this was it. As a result, he spent much of the following decade in exile and prison.

Stalin rose to power during this period, packing committees with his henchmen; falsifying reports; rigging elections; re-writing history; banning all forms of critical debate; and hiring other people to slander rivals. And he did all this claiming to have the highest possible ethical motives. But of course he also took this wholly illegal and paranoid policy to an extreme, and began murdering anyone who opposed him.

Serge helped Trotsky organise the Left Opposition, but by 1927 — the tenth anniversary of the revolution — they were all expelled from the Party. Having been removed from political life Serge once again returned to his role as author, writing articles on the Chinese revolution which were published in France – a factor which later helped to save his life. The appearance of this work abroad was used as the pretext for his first arrest in early 1928, from which he was released after protests from French intellectuals.

Having almost died whilst in prison he decided on release to devote himself to literature – specifically to record the revolution and its aftermath in a series of documentary novels, which turned out to be the double trilogy Men in Prison, Birth of Our Power, Conquered City, Midnight in the Century, The Case of Comrade Tulayev, and Unforgiving Years. There is also the very elusive The Long Dusk and other manuscripts which were confiscated by the secret police and have never been located since. Serge and his family were harassed by the GPU: his mail was opened and his conversations recorded. His wife suffered a nervous breakdown from which she never recovered, dying in a mental institution in the south of France in 1984.

Serge was arrested in 1933, held in solitary confinement, and interrogated endlessly, accused of ‘crimes’ based on the confessions of others which the GPU had actually written. Refusing to co-operate with his captors, he was exiled to Orenberg on the borders of Kazakhstan. He lived there with his son Vlady for the next three years, cold, hungry, and under constant surveillance – but at least free to write. He produced Les Hommes perdus a novel about pre-war French anarchists, and La Tourmente, a sequel to Conquered City. He despatched several copies to Romain Rolland for publication in Paris, but they were ‘lost’ in the post. Ironically, the Post Office was obliged to compensate him for each loss, and he earned ‘as much as a well-paid technician’. He shared the money he earned and the support he received from western Europe with his fellow exiles – on one occasion dividing a single olive with his fellow inmates, who had never tasted one before.

Serge was arrested in 1933, held in solitary confinement, and interrogated endlessly, accused of ‘crimes’ based on the confessions of others which the GPU had actually written. Refusing to co-operate with his captors, he was exiled to Orenberg on the borders of Kazakhstan. He lived there with his son Vlady for the next three years, cold, hungry, and under constant surveillance – but at least free to write. He produced Les Hommes perdus a novel about pre-war French anarchists, and La Tourmente, a sequel to Conquered City. He despatched several copies to Romain Rolland for publication in Paris, but they were ‘lost’ in the post. Ironically, the Post Office was obliged to compensate him for each loss, and he earned ‘as much as a well-paid technician’. He shared the money he earned and the support he received from western Europe with his fellow exiles – on one occasion dividing a single olive with his fellow inmates, who had never tasted one before.

Meanwhile, his supporters in France formed pressure groups to campaign for his release, and eventually Rolland petitioned Stalin in person. This was at the time of the 1936 international congress of writers, and Rolland argued that the continued detention of Serge was causing embarrassment within the congress. Miraculously, Stalin agreed to release him (though he almost immediately regretted his decision) and Serge was released in 1936. But the GPU confiscated his writings as he was crossing the border, bound for Europe.

He settled in Brussels, then Paris- though his papers were not in order, and his political status terribly uncertain. Wherever he went he was pursued by vilification from the orthodox Communists (whose orders were all dictated from Moscow) and by Stalin’s secret agents. He was sustained intellectually by his renewed correspondence with Trotsky, who was in exile in Norway at the time. It was the terrible year of 1936 which saw the Moscow show trials and the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Serge wrote on both these topics, but the only outlets for his work were small left-wing journals and newspapers.

Unfortunately at this point in Susan Weissman’s narrative Serge disappears almost completely – to be replaced by detailed accounts of the spies and assassination squads Stalin despatched into Europe in his quest to eliminate all vestiges of the Old Guard. The network spread from the Balkans to the Atlantic, and even crossed into the USA. There is also a protracted account of the misunderstandings and the spat between Serge and Trotsky which makes them both seem like petulant sixth-formers arguing over the results of a cricket match – even though the issues of contention were the Fourth International and the prospects for the working class at a time of rising fascism, Stalinist totalitarianism, and the growing prospects of war.

The last part of Weissman’s account covers almost a decade and one of the most fertile periods of Serge’s career – and yet it’s over in what seem like a few pages. It begins with the fall of France in June 1940. Serge left on the very day that the Nazis entered Paris, fleeing along with thousands of others for the unoccupied South along with Vlady and Laurette Séjourné, who was twenty years younger than him and was to become his third wife. This defeat at the hands of ‘the twin totalitarianisms’ and the fight for survival were to be documented in his novel Les Derniers Temps (The Long Dusk in English translation). They arrived almost penniless in Marseilles, only to learn of the assassination of Trotsky in Mexico. Serge was one of the last Oppositionists left alive, and he knew his name would be on the GPU’s hit list.

Fortunately, they were rescued thanks to the efforts of Varian Fry and the American Relief Committee which helped to smuggle hundreds of refugees out of France under the very noses of the Gestapo. There was an amazingly idyllic period of a few month when Fry hosted a group of artists, intellectuals, and even surrealists at a large chateau on the outskirts of the city – but Serge was eventually asked to leave because his reputation as a Trotskyist was putting other people at risk. He finally got away from France in March 1941 on a ship bound for Mexico.

En route Serge was separated from his luggage, which had been labelled as destined for the USA, where his publisher Dwight Macdonald (editor of the Partisan Review) had offered him hospitality. The contents of the suitcases were confiscated and photographed by the FBI, which then translated all the manuscripts and compiled summaries which were sent for the personal attention of J. Edgar Hoover.

Serge was interned and interrogated in both Martinique (under French Vichy control) and the Dominican Republic, then put into a concentration camp in Cuba, finally arriving in Mexico in September 1941. The last years of his life were spent in poverty, ill-health, and what he felt as a terrible intellectual loneliness – but at least he could write. This was the period in which he produced his most mature work, the late masterpieces Memoirs of a Revolutionary, The Case of Comrade Tulayev, and Unforgiving Years. There was also The Long Dusk, though he himself considered that something of a failure. He also continued his work on political, economic, and social theory – trying to make sense of a world which by the mid 1940s had seen tens of millions of people killed by both the Nazis and by Stalin.

His ending was as grim as his life had been – cut short by a heart attack after hailing a taxi in Mexico City, dressed in a threadbare suit and with holes in his shoes. His son Vlady suspected he had been poisoned, and even wondered if his stepmother might have been responsible. Serge’s marriage had not been a success, and shortly after Serge’s death Laurette Séjourné married a prominent Mexican Communist and even joined the Communist Party herself.

So – what is to be made of this monumental piece of scholarship? I was disappointed to realise that Susan Weissman’s account of Serge’s political ideas begins in 1917, as he made his way to Russia, which he regarded as his homeland, despite never having lived there. There is no account of the formation of his beliefs and his ‘education’ as a young man (he barely went to school at all, in the sense we know it) and his politicisation as the son of a Russian oppositionist, nor of his radicalisation whilst working as a a printer and a type-setter in Brussels. Neither is there any real attempt to look in detail at his years flirting with anarcho-syndicalists.

A consideration of these early years of Serge’s life are important because it was the skills he had acquired as a self-educated scholar, a linguist, a writer, a printer, and an editor which enabled him to take such an active part in the early days of the Russian revolution, where he worked as a political organiser, propagandist, author, editor, translator, secretary, and even secret agent. His knowledge of anarchism and syndicalism also had an effect on both his theoretical understanding of Marxism and his practice as a revolutionary.

Susan Weissman’s account also seeks to put Serge in the right at every step of his career – even though for a number of years he was working essentially as an agent for the Comintern. It’s true that he thought the formation of the Cheka (the Bolshevik’s secret police) was the first big mistake of the revolutionaries; but this opinion was only formed later. He suggested alternative strategies at the crisis of the Kronstadt rebellion, but ultimately sided with the Party in its tragic massacre of the sailors and workers. And he was amongst the first to identify totalitarian elements within Soviet society and the way it was being governed; but he remained loyal to the Party in what he later called ‘Party patriotism’ – that is, the Party can do no wrong.

This was the major weakness in their policy – Serge (and others) believed in the infallibility of the Party; they believed in their own slogans and rhetoric; and they were very slow to acknowledge the complete divide between aspirations, theory, and the reality of the world in which they lived. They clung to the completely deluded idea that the Party was right because it represented the will of the working class – neither of which suppositions were logically tenable or practically correct. Serge was fortunate enough to eventually reject this supposition – and it helped to save his life.

Susan Weissman rightly gives her account the sub-title ‘A Political Biography’ – because it is not anything like a biography in the conventional sense. There is no account of the first twenty-seven years of Serge’s life; hardly any details of his personal or family life (he was married three times); and no account of where and how he managed to live with apparently no regular source of income. What we get in abundance is a tracking of the debates which fuelled his confidence in the importance of the Russian revolution and his conviction that it should be rescued from the clutches of the Stalinist counter-revolution. There is impeccable scholarly referencing throughout, but very little of the fluency, the facts, the details, and the sap of real life.

In fact this is a biography Susan Weissman has been writing for more than two decades. She published Victor Serge: The Course is Set on Hope in 2001 with the same publisher – and my copy of the latest version still has this sub-title on the title page. although this version has been brought up to date with more recent research, there is very little acknowledgement of the fact in the text. The original publication was based on a 1991 PhD thesis entitled ‘Victor Serge: Political, social and literary critic of the USSR, 1917-1947; the reflections and activities of a Belgo-Russian Revolutionary caught in the orbit of Soviet political history’ — which would explain the first half of the unexamined lifespan, the plethora of historical and political detail, and the paucity of human interest. A review of the original publication by the Serge scholar Richard Greeman which makes similar points is available here.

Susan Weissman has devoted huge amounts of scholarly discipline to this enterprise – and has even made attempts to recover the ‘lost manuscripts’ of Serge’s work confiscated by the secret police. The publication carries an enormous record of Serge’s writings, a series of potted biographies, and a gigantic bibliography of sources which make this an unmissable publication for anybody interested in Serge’s life – but I think the definitive biography has still to be written.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2014

Susan Weissman. Victor Serge: A Political Biography, London and New York: Verso/New Left Books, 2013, pp.406, ISBN: 1844678873

More on Victor Serge

Twentieth century literature

More on biography

The whole sweep of his life as a writer, intellectual, historian, and revolutionary is covered in his autobiographical

The whole sweep of his life as a writer, intellectual, historian, and revolutionary is covered in his autobiographical  Susan Weissmann’s

Susan Weissmann’s

It is astonishing to realise that alongside all his political activities and his time spent as a historian and novelist, Serge also found time to write on literary theory. His

It is astonishing to realise that alongside all his political activities and his time spent as a historian and novelist, Serge also found time to write on literary theory. His

1882. Virginia Woolf born (25 Jan) Adeline Virginia Stephen, third child of Leslie Stephen (Victorian man of letters – first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography) – and Julia Duckworth (of the Duckworth publishing family). Comfortable upper middle class family background. Her father had previously been married to the daughter of the novelist William Makepeace Thackery. Brothers Thoby and Adrian went to Cambridge, and her sister Vanessa became a painter. Virginia was educated by private tutors and by extensive reading of literary classics in her father’s library.

1882. Virginia Woolf born (25 Jan) Adeline Virginia Stephen, third child of Leslie Stephen (Victorian man of letters – first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography) – and Julia Duckworth (of the Duckworth publishing family). Comfortable upper middle class family background. Her father had previously been married to the daughter of the novelist William Makepeace Thackery. Brothers Thoby and Adrian went to Cambridge, and her sister Vanessa became a painter. Virginia was educated by private tutors and by extensive reading of literary classics in her father’s library. Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. An attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject.

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. An attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject. The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf