novelist, essayist, diarist, biographer

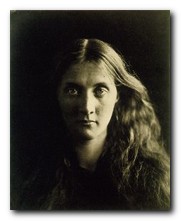

1882. Virginia Woolf born (25 Jan) Adeline Virginia Stephen, third child of Leslie Stephen (Victorian man of letters – first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography) – and Julia Duckworth (of the Duckworth publishing family). Comfortable upper middle class family background. Her father had previously been married to the daughter of the novelist William Makepeace Thackery. Brothers Thoby and Adrian went to Cambridge, and her sister Vanessa became a painter. Virginia was educated by private tutors and by extensive reading of literary classics in her father’s library.

1882. Virginia Woolf born (25 Jan) Adeline Virginia Stephen, third child of Leslie Stephen (Victorian man of letters – first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography) – and Julia Duckworth (of the Duckworth publishing family). Comfortable upper middle class family background. Her father had previously been married to the daughter of the novelist William Makepeace Thackery. Brothers Thoby and Adrian went to Cambridge, and her sister Vanessa became a painter. Virginia was educated by private tutors and by extensive reading of literary classics in her father’s library.

1895. Death of her mother Julia Stephen. VW has the first of many nervous breakdowns.

1896. Travels in France with her sister Vanessa.

1897. Death of half-sister, Stella. VW learning Greek and History at King’s College London.

1899. Brother Thoby Stephen enters Trinity College, Cambridge and subsequently meets Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, and Clive Bell. These Cambridge friends subsequently become known as the Bloomsbury Group, of which VW was an important and influential member.

1904. Death of father. Beginning of second serious breakdown. VW’s first publication is an unsigned review in The Guardian. Travels in France and Italy with her sister Vanessa and her friend Violet Dickinson. VW moves to Gordon Square in Bloomsbury. Other residents of this Square include Lady Jane Strachey, Charlotte Mew, and Dora Carrington.

1905. Travels in Spain and Portugal. Writes book reviews and teaches once a week at Morley College, London, an evening institute for working men and women.

1906. Travels in Greece. Death of brother Thoby Stephen. Writes a group of short stories now collected as Memoirs of a Novelist.

1907. Marriage of sister Vanessa to Clive Bell. VW moves with brother Adrian to live in Fitzroy Square. Working on her first novel (to become The Voyage Out).

1908. Visits Italy with the Bells.

1909. Lytton Strachey [homosexual] proposes marriage. VW meets Ottoline Morell, visits Bayreuth and Florence.

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. An attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject.

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. An attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject.

![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

1910. Works for women’s suffrage. Spends time in a nursing home in Twickenham. First exhibition of Post-Impressionist painters arranged by Roger Fry.

1911. VW moves to Brunswick Square, sharing house with brother Adrian, Maynard Keynes, Duncan Grant, and Leonard Woolf. Travels to Turkey.

1912. Marries Leonard Woolf. Travels for honeymoon to Provence, Spain, and Italy. Moves to Clifford’s Inn.

1913. Mental illness and her first attempted suicide. Put in care of husband and nurses.

1915. Purchase of Hogarth House, Richmond. The Voyage Out published and well received. Another bout of violent madness.

1916. Lectures to Richmond branch of the Women’s Co-Operative Guild. regular work for the Times Literary Supplement [whose reviews were at that time anonymous].

1917. L and VW buy hand printing machine and establish the Hogarth Press. First publication Monday or Tuesday. Later goes on to publish T.S. Eliot, Freud, and VW’s own books.

1919. Purchase of Monk’s House, Rodmell. Night and Day published. Brief friendship with Katherine Mansfield. Both are conscious of experimenting with the substance and the style of prose fiction.

1920. Works on journalism and Jacob’s Room.

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf is collection of essays which addresses the full range of her intellectual perspectives – literary, artistic, philosophical and political. It provides new readings of all nine novels and fresh insight into Woolf’s letters, diaries and essays. The progress of Woolf’s thinking is revealed from Bloomsbury aestheticism through her hatred of censorship, corruption and hierarchy to her concern with all aspects of modernism.

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf is collection of essays which addresses the full range of her intellectual perspectives – literary, artistic, philosophical and political. It provides new readings of all nine novels and fresh insight into Woolf’s letters, diaries and essays. The progress of Woolf’s thinking is revealed from Bloomsbury aestheticism through her hatred of censorship, corruption and hierarchy to her concern with all aspects of modernism.

1921. The Mark on the Wall published. VW ill for most of the summer.

1922. Jacob’s Room published. MeetsVita Sackville-West with whom she has a brief love affair. Writing encouraged by E.M. Forster, Strachey, and Leonard Woolf.

1923. Visits Spain. Works on ‘The Hours’ – an early version of Mrs Dalloway.

1924. Purchase of lease on house in Tavistock Square. Gives lecture that becomes ‘Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown’.

1925. The Common Reader [essays] and Mrs Dalloway published. Major break with the traditional novel, its form and techniques.

1926. Unwell with German measles. Starts writing To the Lighthouse.

1927. To the Lighthouse published. Travels to France and Sicily. Begins Orlando.

1928. Orlando published – a fantasy dedicated to and based upon the life of Vita Sackville-West and her love of her ancestral home at Knole in Kent. Delivers lectures at Cambridge on which she based A Room of One’s Own.

1929. A Room of One’s Own published – essays on women’s exclusion from literary history which have become of seminal importance in feminist studies. Travels to Berlin.

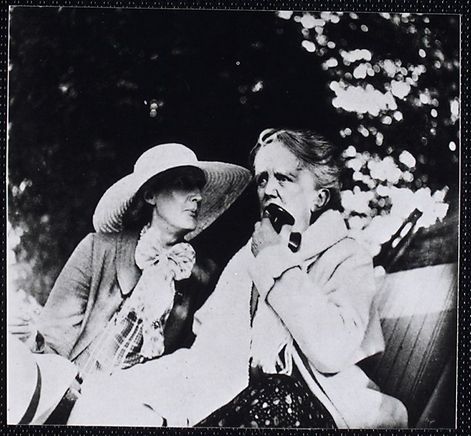

1930. First meets Ethel Smyth – pipe-smoking feminist composer, who falls in love with VW. Finishes first version of The Waves.

1931. The Waves – a novel composed of the thoughts of six characters which takes VW’s literary experimentation to its natural limits.

1932. Death of Lytton Strachey. Begins ‘The Partigers’ which was to become The Years.

1934. Death of Roger Fry. Rewrites The Years.

1935. Rewrites The Years. Car tour through Holland, Germany, and Italy.

1936. Begins Three Guineas – a ‘sequel’ to A Room of One’s Own.

1938. Three Guineas extends the feminist critique of patriarchy, militarism, and privilege started in A Room of One’s Own.

1939. Moves to Mecklenburgh Square, but lives mainly at Monk’s House. Meets Freud in London.

1940. Biography of Roger Fry published. London homes damaged or destroyed in blitz.

1941. VW completes Between the Acts, her last novel, then fearing the madness which she felt engulfing her again, fills her pockets with stones and drowns herself in the River Ouse, near Monk’s House. [Her dates of 1882- 1941 are exactly those of James Joyce.]

Bloomsbury Group – web links

![]() Hogarth Press first editions

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, featuring designs by Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and others.

![]() The Omega Workshops

The Omega Workshops

A brief history of Roger Fry’s experimental Omega Workshops, which had a lasting influence on interior design in post First World War Britain.

![]() The Bloomsbury Group and War

The Bloomsbury Group and War

An essay on the largely pacifist and internationalist stance taken by Bloomsbury Group members towards the First World War.

![]() Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Mini web site featuring photos, paintings, a timeline, sub-sections on the Omega Workshops, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant, and biographical notes.

![]() Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Exhibition of paintings, designs, and ceramics at Toronto University featuring Hogarth Press, Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Quentin Bell, and Stephen Tomlin.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

A rich enthusiast site featuring news of events, exhibitions, new book reviews, relevant links, study resources, and anything related to Bloomsbury and Virginia Woolf

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search the texts of all Woolf’s major works, and track down phrases, quotes, and even individual words in their original context.

![]() A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

An annotated description of Clarissa Dalloway’s walk from Westminster to Regent’s Park, with historical updates and a bibliography.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Annotated tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury, including Gordon Square, University College, Bedford Square, Doughty Street, and Tavistock Square.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

News of events, regular bulletins, study materials, publications, and related links. Largely the work of Virginia Woolf specialist Stuart N. Clarke.

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

A charming sound recording of a BBC radio talk broadcast in 1937 – accompanied by a slideshow of photographs of Virginia Woolf.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephens’ collection of family photographs which became known as the Mausoleum Book, collected at Smith College – Massachusetts.

![]() Bloomsbury at Duke University

Bloomsbury at Duke University

A collection of book jacket covers, Fry’s Twelve Woodcuts, Strachey’s ‘Elizabeth and Essex’.

© Roy Johnson 2000-2014

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Vita (Victoria Mary) Sackville-West (1892-1962) was a prolific poet and novelist – though she is probably best known for her writing on gardens and her affair with

Vita (Victoria Mary) Sackville-West (1892-1962) was a prolific poet and novelist – though she is probably best known for her writing on gardens and her affair with