tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

The Real Right Thing first appeared in Collier’s Weekly for December 1899 at a time when Henry James was producing a number of his famous ghost stories. Its first publication in book form was in The Soft Side in 1900, alongside tales such as The Third Person, The Tree of Knowledge, John Delavoy, The Great Condition, and Miss Gunton of Poughkeepsie.

The Real Right Thing – critical commentary

This tale is something of a curiosity. It is one of the shortest of all James’s tales – less than 5,000 words – and has a number of elements that suggest that he might have been in two minds regarding the inner purpose of the narrative.

Biography

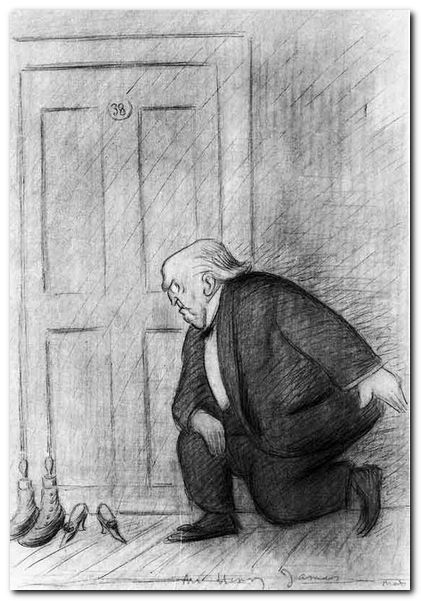

With regard to the overt subject matter – the biography of a writer – there is certainly no doubt that James was very conscious of matters regarding privacy, indiscretions, revelations, and the dangers of the exposure of a writer’s life to public scrutiny. He made a ‘bonfire’ of his own personal papers, and wrote a number of other stories on this theme which essentially support the idea that writers are entitled to their privacy, even after death. The most famous example is The Aspern Papers.

Withermore becomes gradually conscious that Ashton Doyne might not wish to have his ‘life’ exposed to the public, and coupled with the ‘ghost story’ element of the narrative, the biographical project is abandoned. In this sense, the story is a triumph for the dead writer, and possibly even a wish-fulfilment on James’s part, since he certainly had things to conceal from the public in his own life.

Mrs Doyne

But there are other curiosities. Mrs Doyne is introduced as a Dickensian harpy , an almost grotesque figure: ‘her big black eyes, he big black wig, her big black fan and gloves, her general gaunt, ugly, tragic … presence’. She also has a curious habit of speaking from behind the fan, which she holds up to conceal her face.

She is also presented as a rather ambiguous figure, with two implications that there was something seriously amiss in her relationship with her husband:

Doyne’s relationships with his wife had been, to Withermore’s knowledge, a very special chapter — which would present itself, by the way, as a very delicate one for the biographer … She had not taken Doyne seriously enough in life, but the biography should be a solid reply to every imputation on herself.

But having set up these tantalising hints, James makes nothing more of this issue in the rest of the story, which then becomes another variation of the ‘ghostly tale’.

The ghost story

James was a great devotee of the ghost story – and he prided himself in avoiding the contemporary clichés of the genre. His greatest work of this type is of course his macabre and chilling The Turn of the Screw, but he also produced variations such as the comic ghost story The Third Person and a tale which actually contains a benevolent ghost in Sir Edmund Orme.

James is very good at creating the elements of suspense and mystery associated with ghost stories – which were very popular at the end of the nineteenth century. The year before (1898) he had successfully summoned up the images of Peter Quint and Miss Jessel in The Turn of the Screw without ever describing them. His method (or literary conjurer’s trick) is to have his protagonists imagine the ghosts – and readers are invited to share this vision.

The governess in The Turn of the Screw never actually sees Peter Quint or Miss Jessel: she imagines she has seen them, and wishes them into being. And here in The Real right Thing Withermore (and Mrs Doyne) feel the presence of Ashton Doyne’s spirit. James does not resort to any hackneyed spectral presences, no ectoplasms, or shadows behind the curtain. Withermore invokes the spirit of Ashton Doyne because he is writing in his room; he is surrounded by his furniture, and his personal effects. He is also delving into his private life to create the biography.

So James has him sense the presence of the dead Ashton Doyne, guarding his own work and reputation. It is almost as if the ghost is a transferred embodiment of Withermore’s guilty conscience. He wonders about the desirability of creating a biography the moment he sets to work on it.

But in The Real Right Thing there is neither innovation nor explanation. Withermore begins to feel empathetically close to Doyne because he is working in the author’s study, and at first he feels his biographical research is being assisted by the spirit of the ‘great’ man. But then for no particular reason that is given to us, the influence turns negative, and Withermore begins to have doubts.. Then he feels that the spirit of Doyne is positively blocking his efforts and finally even access to the study. When Mrs Doyne urges him to continue with his efforts, even she is unable to gain access to the room, which we are led to believe is being ‘guarded’ by Doyne’s spirit.

This is not very persuasive, and the tale comes to a rather abrupt end with the abandonment of the projected biography. All in all, the tale does not hang together very well to compare with the best that James wrote on the same theme.

Structural weakness

At around 5,000 words this is certainly the shortest of James’s tales, but also probably one of the least successful. It deals with a subject very close to James’s own heart in the later phase of his life – a fear that inquisitive biographers might spoil the carefully cultivated public image of the successful auteur.

James protected his own reputation by burning all his private papers and writing his own biography. He promoted the idea that a writer’s standing should be based on his work, and should not be sullied by any unsavoury details from his private life. As it is expressed in this tale ‘The artist was what he did – he was nothing else’. And confirmed bachelor Henry James also had (as we now know) something to hide, as he gave way to the homo-erotic impulses he increasingly felt.

The story begins well enough with all the ingredients of a potentially complex narrative: an inexperienced biographer with doubts regarding his task; access to all the great writer’s papers; and a widow with ambiguous motives. Similar ingredients had produced the masterpiece The Aspern Papers ten years previously.

Mrs Doyne is a figure almost out of Grand Guignol: Withermore is struck by ‘her big black eyes, her big black wig, her big black fan and gloves’. And she is later described as a figure like ‘some ‘decadent’ coloured print, some poster of the newest school’. She speaks from behind her fan, covering her lower face. There is every reason to believe (at first) that she might be secretly controlling the ‘special box or drawers’ and the ‘opening of an old journal at the very date he wanted’ which guide Withermore’s efforts. But nothing is made of this dramatic character. She is at first ambiguous, but then she simply colludes with Withermore in his supposition that the spirit of Doyne is guarding his reputation.

This dramatic weakness reinforces the more important structural flaw in the story – that having first ‘encouraged’ Withermore’s efforts in Part II, the spirit then turns against him to deter his efforts in Part III. No reason is provided for this change. Withermore is simply enthusiastic one moment, then despondent the next. The only logical explanation for the differences between Parts II and III is inconsistency or a change of mind on Withermore’s part. And the fact that the entire project of the biography is abandoned amplifies the sense of bathos. Nothing is achieved.

The Real Right Thing – study resources

![]() The Ghost Stories of Henry James – Wordsworth edn – Amazon UK

The Ghost Stories of Henry James – Wordsworth edn – Amazon UK

![]() The Ghost Stories of Henry James – Wordsworth edn – Amazon US

The Ghost Stories of Henry James – Wordsworth edn – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() The Real Right Thing – Gutenberg Consortia eBook

The Real Right Thing – Gutenberg Consortia eBook

The Real Right Thing – plot summary

Part I. On the death of the writer Ashton Doyne, his widow commissions his younger colleague George Withermore to write a biography. She gives Withermore free access to all Doyne’s papers and invites him to use Doyne’s former study as a place of work. Withermore realises that writing a biography will bring him into intimate contact with his former colleague, more so than when he was alive.

Part II. Withermore feels that Mrs Doyne is watching him, but they agree that the ‘spirit’ of Doyne they both feel present will help them in the enterprise and should be encouraged. As he reads more of Doyne’s private papers Withermore feels himself more closely connected with his subject, and he feels that Doyne is almost present in the room, helping him in his researches and composition.

Part II. Withermore is distressed to realise that he is disconcerted when the presence of Doyne’s spirit is not available to him. On one such occasion he compares notes with Mrs Doyne and they feel that Doyne’s spirit somehow passes between them. Withermore begins to feel that he is delving too deeply into Doyne’s life, and when the spirit reappears it is a warning against such intrusion. He fears that if he continues to work on the biography it will invoke Doyne’s disapproval. He finally tests this notion by approaching the study, only to find Doyne’s spirit forbidding entry. Mrs Doyne checks and finds the same – so they agree to abandon the projected biography.

Principal characters

| Ashton Doyne | a ‘great’ writer, recently deceased |

| Mrs Doyne | his ugly widow, who wears a black wig and speaks from behind a black fan |

| George Withermore | a young and inexperienced newspaper journalist |

Henry James’s study

Ghost stories by Henry James

![]() The Romance of Certain Old Clothes (1868)

The Romance of Certain Old Clothes (1868)

![]() The Ghostly Rental (1876)

The Ghostly Rental (1876)

![]() Sir Edmund Orme (1891)

Sir Edmund Orme (1891)

![]() The Private Life (1892)

The Private Life (1892)

![]() Owen Wingrave (1892)

Owen Wingrave (1892)

![]() The Friends of the Friends (1896)

The Friends of the Friends (1896)

![]() The Turn of the Screw (1898)

The Turn of the Screw (1898)

![]() The Real Right Thing (1899)

The Real Right Thing (1899)

![]() The Third Person (1900)

The Third Person (1900)

![]() The Jolly Corner (1908)

The Jolly Corner (1908)

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

Mrs Yeobright checks on the money with Eustacia and they argue about Clym. The money is eventually distributed fairly, but Clym becomes estranged from his mother and Eustacia argues more virulently with Mrs Yeobright. Eustacia wants social advancement and the glamour of a life in Paris, but Clym wishes to stay in his local parish and start the school.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes Chance

Chance