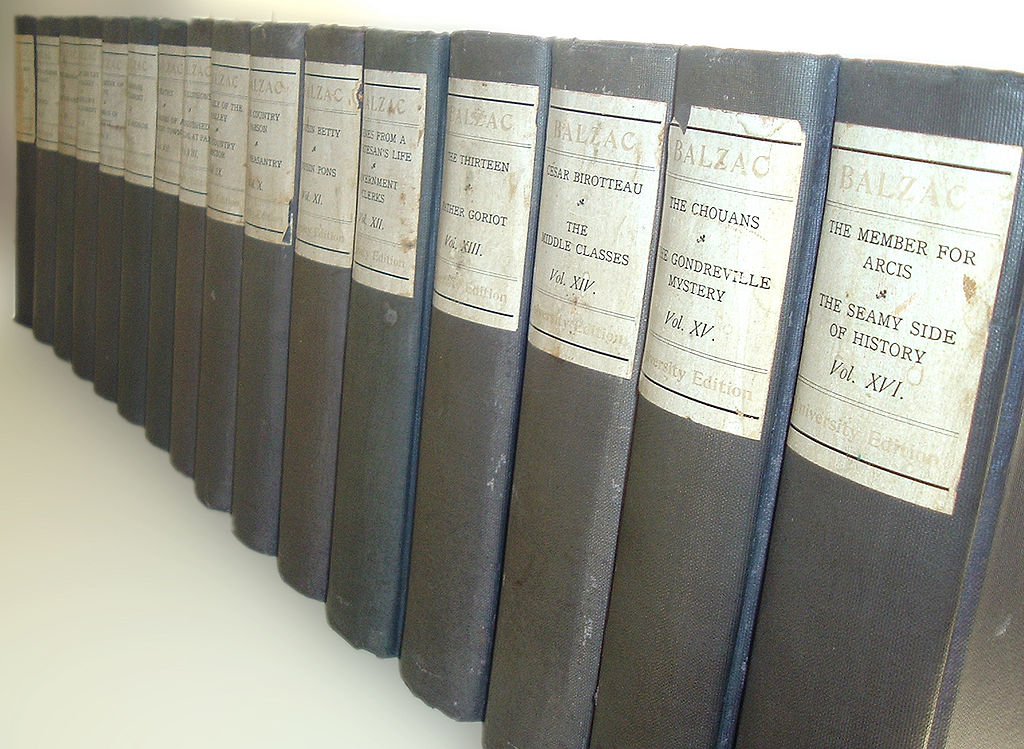

La Comédie Humaine is the title Balzac gave to an epic series of novels and stories he wrote depicting French society in the first part of the nineteenth century. It comprises almost 100 finished and fifty unfinished works. The first parts were written without any overall plan, but by 1830 he began to group his first novels into a series called ‘Scènes de la vie privée’.

In 1833, with the publication of Eugenie Grandet, he envisioned a second series called ‘Scènes de la vie de province’. He also devised the strategy of creating characters who were introduced in one novel and then reappeared in another.

This literary technique was a direct reflection of the fact that his novels were serialised in newspapers and magazines. Serial publication was the nineteenth century equivalent of the modern soap opera and the twenty-first century television drama series. Balzac first used this device in his novel of 1834, Le Père Goriot.

He then devised an even more elaborate structure for subsequent works which included private, provincial, and Parisian life, plus political, military, and country life. As the stories, novellas, and novels were moved from one part of this conceptual framework to another, he changed their titles and put them into new groups.

As an enterprising businessman, he also re-published the works in book format and made more money out of the same product. However, he was always hopelessly insolvent – largely because of his lavish life style and because he was paying off the debts on various failed business enterprises.

The logic of this structural framework for his fiction is not always convincing. Lost Illusions for instance is categorised as part of ‘Scenes from Provincial Life’ – and it’s true that the events of the narrative begin and end in Angouleme in south-west France. Yet the majority of the novel takes place in Paris, in a very urban, indeed a metropolitan city.

Balzac actually believed that his grand design and enterprise was something of a quasi-scientific study or research project:

Society resembles nature. For does not society modify Man, according to the conditions in which he lives and acts, into men as manifold as the species in Zoology?

This is essentially a materialist philosophy of the world – one which sees the larger forces in society shaping how people behave and what they believe – rather than the other way round. It is very close to what Marx and Engels only a few years later formulated as classic Marxism. This possibly explains why Balzac was one of the writers they most admired, because he revealed the links between capital accumulation and the ideology of the ruling class.

Balzac also regarded himself as a historian of manners, basing the wide scope of his scheme on the example of Walter Scott, whose work was popular throughout Europe at that time.

French society would be the real author. I should only be the secretary.

He believed that his work should vigorously exalt the Catholic Church and the Monarchy. But he also thought that it was his duty to show the real social forces at work as people fought for their existence in what we would now call a Darwinian struggle for survival. Fortunately for us, his artistic beliefs outweigh his religious and political opinions – though it has to be said that there are many passages of overt proselytising in his work.

Given the interlocking nature of these works and taking into account the huge scale of his endeavour, it is not surprising that the scheme was never completed. Balzac was dead by the age of fifty-two – worn out with overwork.

Notwithstanding the incomplete nature of this grand project, one glance at the lists below reveals the prodigious nature of Balzac’s sheer productivity. There are years in which he wrote not one but two and even three novels that are now considered masterpieces of European literature.

La Comedie Humaine

Scenes de la vie privee

1829. At the Sign of the Cat and Racket (novel)

1830. The Ball at Sceaux (novella)

1830. Vendetta (novella)

1830. A Second Home (novella)

1830. Study of a Woman (story)

1830. Domestic Peace (story)

1830. Gobseck (novel)

1831. The Grand Breteche (story)

1832. La Grenadiere (story)

1832. The Deserted Woman (story)

1832. Madame Firmiani (story)

1832. A Woman of Thirty (novel)

1832. Colonel Chabert (novella)

1832. The Purse (story)

1834. Father Goriot (novel)

1835. The Atheist’s Mass (story)

1835. The Marriage Contract (novel)

1836. The Commission in Lunacy (novella)

1836. Albert Savarus (novella)

1838. A Daughter of Eve (novel)

1839. Beatrix (novel)

1841. Letters of Two Brides (novel)

1842. A Start in Life (novel)

1842. Another Study of Woman (story)

1843. The Imaginary Mistress (novella)

1843. Honorine (novella)

1844. Modeste Mignon (novel)

Scenes from Provincial Life

1832. The Vicar of Tours (novella)

1833. Eugenie Grandet (novel)

1833. The Illustrious Gaudissart (story)

1836. The Old Maid (novel)

1837. Two Poets (novel)

1839. The Collection of Antiquities (novel)

1839. A Distinguished Provincial (novel)

1840. Pierrette (novel)

1841. Ursule Mirouet (novel)

1842. The Black Sheep (novel)

1843. The Muse of the Department

1843. Eve and David (novel)

Scenes from Parisian Life

1836. Facino Cane (story)

1837. Cesar Birotteau (novel)

1837. A Harlot High and Low (novel)

1838. The Firm of Nucingen (novel)

1838. Esther Happy (novel)

1838. The Government Clerks

1838. The Wrong Side of Paris

1840. Secrets of the Princessm de Cadignan

1840. Sarrasine (novella)

1840. Pierre Grassou (story)

1843. What Love Costs an Old Man (novel)

1844. A Prince of Bohemia

1846. The End of Evil Ways (novel)

1846. A Man of Business

1846. Gaudissart II

1846. The Unconscious Comedians

1847. The Last Incarnation of Vautrin (novel)

1854. The Lesser Bourgeoisie

The Thirteen

1833. Ferragus (novel)

1834. The Duchess of Langeais (novel)

1835. The Girl with the Golden Eyes (novel)

Poor Relations

1846. Cousin Bette (novel)

1847. Cousin Pons (novel)

Scenes from Political Life

1830. An Episode Under the Terror (story)

1840. Z. Marcas (novella)

1841. A Murky Business (novel)

1847. The Election

Scenes from Military Life

1829. The Chouans (novel)

1830. A Passion in the Desert

Scenes from Country Life

1833. The Country Doctor (novel)

1835. The Lily of the Valley (novel)

1839. The Village Rector (novel)

1844. The Peasants

Philosophical Studies

1830. Farewell

1830. El Verdugo (story)

1831. The Conscript (story)

1831. The Wild Ass’s Skin (novel)

1831. The Hated Son

1831. Christ in Flanders

1831. The Unknown Masterpiece (story)

1831. Maitre Cornelius

1831. The Red Inn (story)

1831. The Elixir of Life

1831. The Exiles (novel)

1832. Louis Lambert (novel)

1834. The Quest of the Absolute (novel)

1834. A Drama on the Seashore (story)

1834. The Maranas

1835. Melmoth Reconciled

1835. Seraphita (novel)

1837. Gambara (story)

1839. Massimilia Doni (story)

1842. About Catherine de Medici

Analytical Studies

1829. The Physiology of Marriage

1846. Little Miseries of Conjugal Life

© Roy Johnson 2018

More on Honore de Balzac

More on literary studies

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first.

He reverted to an old-fashioned strategy for publication and raised money by subscriptions, comissioning a Florentine bookseller named Guiseppe Orioli to print the book in his Tipografia Giuntina using Lawrence’s own capital. The 1,000 copies of this first edition printed in July 1928 were sold through Lawrence’s close personal friends. At only two pounds, the book sold quickly, so that by December, this first version was completely sold out. In November, he published another cheaper edition of 200 copies which sold just as quickly as the first. Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Connie longs for real human contact, and falls into despair, as all men seem scared of true feelings and true passion. There is a growing distance between Connie and Clifford, who has retreated into the meaningless pursuit of success in his writing and in his obsession with coal-mining, and towards whom Connie feels a deep physical aversion. A nurse, Mrs. Bolton, is hired to take care of the handicapped Clifford so that Connie can be more independent, and Clifford falls into a deep dependence on the nurse, his manhood fading into an infantile reliance on her services.

Sons and Lovers

Sons and Lovers Women in Love

Women in Love