The biography of Beckett by Deirdre Bair [Samuel Beckett, 1975], while not having any particular critical pretensions itself, is a very useful adjunct to this list of Samuel Beckett criticism, containing as it does not only the background, context, composition and publishing details of the work but also a good deal of miscellaneous comment and anecdote from Beckett himself and his friends, in the form of interviews and correspondence. Enoch Brater’s Why Beckett (1989) takes the form of a pictorial biography, with over a hundred (often excellent) black-and-white photographs. There are some good points (and quotes) in the succinct text, too.

The biography of Beckett by Deirdre Bair [Samuel Beckett, 1975], while not having any particular critical pretensions itself, is a very useful adjunct to this list of Samuel Beckett criticism, containing as it does not only the background, context, composition and publishing details of the work but also a good deal of miscellaneous comment and anecdote from Beckett himself and his friends, in the form of interviews and correspondence. Enoch Brater’s Why Beckett (1989) takes the form of a pictorial biography, with over a hundred (often excellent) black-and-white photographs. There are some good points (and quotes) in the succinct text, too.

These biographical works have now been superseded by James Knowlson’s Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett (1996), a work of great insight as well as scholarship by someone who was close to Beckett in his last years.

It is inevitably the case that Beckett features, often centrally, in many works on twentieth-century fiction and drama, where his place as an innovator and explorer of extremes is recognized. The Irish context of his work is also receiving more attention than formerly. See for example Beckett: The Irish Dimension by Mary Junker (1995), and the excellent short accounts of Beckett’s work given in Richard Kearney’s Transitions …, Robert Welch’s Changing States: Transformations in Modern Irish Writing (1993), and Declan Kiberd’s Inventing Ireland (1996).

[Works are listed here in chronological order.]

Martin Esslin, The Theatre of the Absurd, New York: Doubleday, 1961.

Ruby Cohn, Samuel Beckett: The Comic Gamut, New Brunswick (NJ): Rutgers University Press, 1962.

Frederick J Hoffman, Samuel Beckett: The Language of Self, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1962.

Martin Esslin (ed), Samuel Beckett: A Collection of Critical Essays, Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice-Hall, 1965.

John Fletcher, The Novels of Samuel Beckett, London: Chatto and Windus, 1964.

Raymond Federman, Journey to Chaos: Samuel beckett’s Early Fiction, Berkley (CA): University of California Press, 1965.

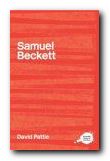

The Complete Critical Guide to Samuel Beckett is a good introduction to the man and the writer. Includes a potted biography of Beckett, an outline of the stories, novels, plays, and poetry, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the 1960s to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist journals.

The Complete Critical Guide to Samuel Beckett is a good introduction to the man and the writer. Includes a potted biography of Beckett, an outline of the stories, novels, plays, and poetry, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the 1960s to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist journals. ![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

John Fletcher, Samuel Beckett’s Art, London: Chatto and Windus, 1967.

Ruby Cohn, A Casebook on ‘Waiting for Godot’, New York: Grove Press, 1967.

Ronald Hayman, Samuel Beckett, London: Heinemann, 1968.

Michael Robinson, The Long Sonata of the Dead: A study of Samuel Beckett, London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1970.

Raymond Federman and John Fletcher, Samuel Beckett: His Work and His Critics, Berkley (CA): University of California Press, 1970

Melvin J. Friedman (ed) Samuel Beckett Now: Critical Approaches to his Novels, Poetry, and Plays, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Francis Doherty, Samuel Beckett, London: Hutchinson, 1971.

Colin Duckworth, Angels of Darkness: Dramatic Effect in Beckett with Special Reference to Ionesco, New York: Barnes and Noble, 1972.

John Fletcher, Beckett: A Study of his Plays, New York: Hill and Wang, 1972.

Brian Finney, ‘How It Is’: A Study of Samuel Beckett’s Later Fiction, London: Covent Garden Press, 1972.

Al Alvarez, Samuel Beckett, New York: Viking, 1973.

Ruby Cohn, Back to Beckett, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Hugh Kenner, A Reader’s Guide to Samuel Beckett, 1973.

H. Porter Abbott, The Fiction of Samuel Beckett, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1973.

Ruby Cohn (ed), Samuel Beckett: A Collection of Criticism, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975.

Hannah-Case Copeland, Art and the Artist in the works of Samuel Beckett, Paris: Mouton, 1975.

James Eliopulos, Samuel Beckett’s Dramatic Language, The Hague: Mouton, 1975.

Katherine Worth (ed), Beckett the Shape Changer, London: Routledge, 1975.

John Pilling, Samuel Beckett, 1976.

S.E. Gontarski, Beckett’s ‘Happy Days’: A Manuscript Study, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1977.

Beryl Fletcher et al, A Student’s Guide to

The Plays of Samuel Beckett, London: Faber and Faber, 1978.

James Knowlson and John Pilling, Frescoes of the Skull: The Later Prose and Drama of Samuel Beckett, 1979.

Robin J. Davis, Samuel Beckett: Checklist and Index of his Published Works, Stirling: The Library: University of Stirling, 1979.

Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life gives a short account of Beckett’s little-known private life in a book which is packed with rare photographs and shots of his stage productions. The life is quite surprising: a priviledged upbringing, with talented academic prospects which he abandonded for a bohemian life. Fighting with the Maquis during the war. Little artistic success, but lots of relationships with women – and then the big breakthrough with Waiting for Godot. This is a stunning little book.

Samuel Beckett: an illustrated life gives a short account of Beckett’s little-known private life in a book which is packed with rare photographs and shots of his stage productions. The life is quite surprising: a priviledged upbringing, with talented academic prospects which he abandonded for a bohemian life. Fighting with the Maquis during the war. Little artistic success, but lots of relationships with women – and then the big breakthrough with Waiting for Godot. This is a stunning little book. ![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

Barbara R. Gluck, Beckett and Joyce: Friendship and Fiction, Lewisberg (PA): Bucknell University Press, 1979.

Lawrence Graver and Raymond Federman, Samuel beckett: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1979.

Ruby Cohn, Just Play: Beckett’s Theatre, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Helene L. Baldwin, Samuel Beckett’s Real Silence, 1981.

John C. DiPierro, Structures in Beckett’s ‘Watt’, York (SC): French Literature Publications, 1981.

J.E. Dearlove, Accommodating the Chaos: Samuel Beckett’s Nonrelational Art, Durham: Duke University Press, 1982.

Lance St. John Butler, Samuel Beckett and the Meaning of Being: A Study in Ontological Parable, 1984.

Virginia Cooke, Beckett on File, London: Methuen, 1985.

S.E. Gontarski, The Intent of ‘Undoing’ in Samuel Beckett’s Dramatic Texts, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Enoch Brater (ed), Beckett at 80/Beckett in Context, 1986.

S.E. Gontarski (ed) On Beckett: Essays and Criticism, New York: Grove Press, 1986.

John Calder (ed), As No Other Dare Fail: for Samuel Beckett on his 80th birthday, 1986.

James Knowlson (ed), Samuel Beckett: A Celebration, 1986.

Eoin O’Brien (ed), The Beckett Country: Samuel Beckett’s Ireland, 1986.

Peter Gidal, Understanding Beckett: A Study of Monologue and Gesture in the Work of Samuel Beckett, London: Macmillan, 1986.

Ruby Cohn (ed) Samuel Beckett: ‘Waiting for Godot’: A Casebook, London: Macmillan, 1987.

Enoch Brater, Beyond Minimalism: Beckett’s Late Style in the Theatre, 1987.

James Acheson and Kateryna Arthur (eds), Beckett’s Later Fiction and Drama: Texts for Company, London: Macmillan, 1987.

Alan Warren Friedman et al, Beckett Translating/ Translating Beckett, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1987.

Jane Alison Hale, The Broken Window: Beckett’s Dramatic Perspective, West Lafayette (IN): Purdue University Press, 1987.

Steven Connor, Samuel Beckett: Repetition, Theory and Text, Oxford: Blackwell, 1988.

Robin J. Davis and Lance St. John Butler (eds) Make Sense Who May: Essays on Samuel Beckett’s Later Works, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1988.

Mary A. Doll, Beckett and Myth: An Archetypal Approach, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1988.

Brian Fitch, Beckett and Babel: An Investigation into the Status of the Bilingual Work, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988.

Lawrence Graver, Samuel Beckett: ‘Waiting for Godot’, London: Thames and Hudson 1989.

Jonathan Kalb, Beckett in Performance, 1989.

Katherine Worth, ‘Waiting for Godot’ and ‘Happy Days’, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1990.

M.R. Axelrod, The Politics of Style in the Fiction of Balzac, Beckett, and Cortazar, 1992.

Steven Connor, ‘Waiting for Godot’ and ‘Endgame’, New York: St Martin’s Press, 1992.

Anna McMullan, Theatre on Trial: Samuel Beckett’s Later Drama, 1993.

Eyal Amiran, Wandering and Home: Beckett’s Metaphysical Narrative, University Park: Pennsylvania University Press, 1993.

Paul Davies, The Ideal Real: Beckett’s Fiction and Imagination, Toronto: Associated University Press, 1994.

Christopher Ricks, Beckett’s Dying Words, 1995.

H. Porter Abbott, Beckett Writing Beckett: The Author in the Autograph, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996.

Anthony Cronin, Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist, London: Harper-Collins, 1996.

James Acheson, Samuel Beckett’s Artistic Theory and Practice: Criticism, Drama, and Early Fiction, New York: St Martin’s Press, 1997.

Thomas Coisineau, ‘Waiting for Godot’: Form in Movement, Boston: Twayne, 1990.

Anthony Farrow, Early Beckett: Art and Allusion in ‘More Pricks than Kicks’ and ‘Murphy’, Try (NY): Whitson, 1991.

S.E. Gontarski (ed) The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett, Vol 2: ‘Endgame’, London: Faber and Faber, 1992.

S.E. Gontarski (ed) The Beckett Studies Reader, Gainsville: University Press of Florida, 1993.

S.E. Gontarski (ed) The Theatrical Notesbooks of Samuel Beckett, Vol 4: The Shorter Plays, London: Faber and Faber, 1993.

Lois Gordon, The World of Samuel Beckett, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Samuel Beckett – web links

![]() Samuel Beckett at Mantex

Samuel Beckett at Mantex

Biographical notes, complete bibliography, selected criticism, book reviews, videos, and web links.

![]() Samuel Beckett Online Resources

Samuel Beckett Online Resources

This is a giant collection of papers, reviews, videos, journals. An old site, but packed with information. It looks very much like a labour of love by an enthusiast.

![]() Samuel Beckett Exhibition at University of Texas

Samuel Beckett Exhibition at University of Texas

Biograhical notes, manuscripts, mini-essays, a timeline, and illustrations.

![]() The Samuel Beckett Endpage

The Samuel Beckett Endpage

Performances, illustrated journals, interviews, and conferences

![]() Samuel Beckett at the Internet Movie Database

Samuel Beckett at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Some very rare examples of television films of Beckett’s shorter and less well known works. Full technical details of directors, actors, and production.

![]() Samuel Beckett at Literary History.com

Samuel Beckett at Literary History.com

Collection of articles on literary criticism, plus reviews.

![]() Echo’s Bones – a newly discovered story

Echo’s Bones – a newly discovered story

![]() Samuel Beckett – at Wikipedia

Samuel Beckett – at Wikipedia

Life and career, Works, Collaborators, Legacy, Honours and awards, Selected works, Further reading, Web links.

© Roy Johnson 1999-2002 – with thanks to Damian Grant

More on Samuel Beckett

Twentieth century literature

More on biography

The Cambridge Companion to Beckett

The Cambridge Companion to Beckett

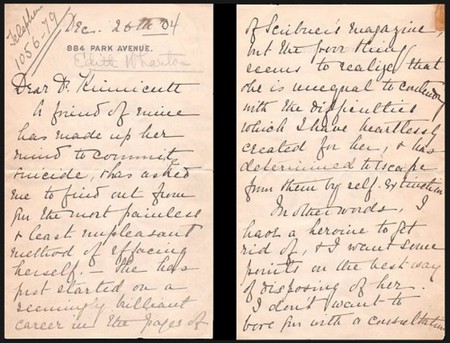

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth Saul Bellow (1915—2005) was born of Russian-Jewish parents in Canada, but lived most of his life in Chicago, a city which features in many of his novels. His work features characters struggling to understand themselves, and searching for identity in an often irrational world. He has a wonderful ear for the rhythms of modern speech, and he captures city life particularly well. Linguistically, he manages to successfully combine an intellectual-philosophical vocabulary with the language of the street. And his narratives are often very funny. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976.

Saul Bellow (1915—2005) was born of Russian-Jewish parents in Canada, but lived most of his life in Chicago, a city which features in many of his novels. His work features characters struggling to understand themselves, and searching for identity in an often irrational world. He has a wonderful ear for the rhythms of modern speech, and he captures city life particularly well. Linguistically, he manages to successfully combine an intellectual-philosophical vocabulary with the language of the street. And his narratives are often very funny. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976. Dangling Man (1944) his first novel, is concerned with existential philosophy and the sense of identity which was much in vogue at the time of its publication. It’s an accomplished debut, thoughtful and serious, about a man who does not want to go into the army. This reflects the serious side of Bellow, who repeatedly inspects the human condition. But it doesn’t have much of the rib-tickling bravura of his later work. This is early Bellow flexing his wings. It is perhaps best appreciated after you have read some of his later works.

Dangling Man (1944) his first novel, is concerned with existential philosophy and the sense of identity which was much in vogue at the time of its publication. It’s an accomplished debut, thoughtful and serious, about a man who does not want to go into the army. This reflects the serious side of Bellow, who repeatedly inspects the human condition. But it doesn’t have much of the rib-tickling bravura of his later work. This is early Bellow flexing his wings. It is perhaps best appreciated after you have read some of his later works. The Adventures of Augie March is an ambitious, rambling, almost picaresque novel. Its first half is a moving and seemingly authentic account of a young boy growing up in Chicago during the Depression – which is where Bellow himself was raised. The story then goes off in a free-wheeling account of a series of bizarre jobs and relationships, and he ends up in Mexico. Bellow’s purpose seems to be to question how much compromise is desirable and how much is necessary, and what make us think about which parts of ourselves we want to remain individual. The second half of the novel however is far less coherent and less credible than the first – but some critics think otherwise.

The Adventures of Augie March is an ambitious, rambling, almost picaresque novel. Its first half is a moving and seemingly authentic account of a young boy growing up in Chicago during the Depression – which is where Bellow himself was raised. The story then goes off in a free-wheeling account of a series of bizarre jobs and relationships, and he ends up in Mexico. Bellow’s purpose seems to be to question how much compromise is desirable and how much is necessary, and what make us think about which parts of ourselves we want to remain individual. The second half of the novel however is far less coherent and less credible than the first – but some critics think otherwise. Seize the Day (1956) is a novella in which you get a sense of Bellow finding his true voice. It’s a light, swift work with dark shadows that looks at the events of one day in the life of Tommy Wilhelm, a fading charmer. He confronts his sense of personal failure and a love-hate relationship with his father. This is his day of reckoning and he is scared. In his 40s, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of this one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. This is a short work which is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a good novella. It is now widely regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works.

Seize the Day (1956) is a novella in which you get a sense of Bellow finding his true voice. It’s a light, swift work with dark shadows that looks at the events of one day in the life of Tommy Wilhelm, a fading charmer. He confronts his sense of personal failure and a love-hate relationship with his father. This is his day of reckoning and he is scared. In his 40s, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of this one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. This is a short work which is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a good novella. It is now widely regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works. Henderson the Rain King (1959) was his first major success. It is a comic character study of American millionaire Gene Henderson, a larger-than-life 55-year-old who has accumulated money, position, and a large family, yet nonetheless feels unfulfilled. The story plots his frustrations with modern life, and his quest for revelation and spiritual enlightenment in Africa, where he fights with a lion, is hailed as a rainmaker, and becomes heir to a kingdom. He meets two tribes, one of which he virtually destroys in an attempt to purify their main water supply of a plague of frogs which goes disastrously wrong. Much of the novel’s humour derives from such antics from Henderson, a character-exaggeration clearly based on Ernest Hemingway (who was a highly regarded writer and public figure at the time).

Henderson the Rain King (1959) was his first major success. It is a comic character study of American millionaire Gene Henderson, a larger-than-life 55-year-old who has accumulated money, position, and a large family, yet nonetheless feels unfulfilled. The story plots his frustrations with modern life, and his quest for revelation and spiritual enlightenment in Africa, where he fights with a lion, is hailed as a rainmaker, and becomes heir to a kingdom. He meets two tribes, one of which he virtually destroys in an attempt to purify their main water supply of a plague of frogs which goes disastrously wrong. Much of the novel’s humour derives from such antics from Henderson, a character-exaggeration clearly based on Ernest Hemingway (who was a highly regarded writer and public figure at the time). Herzog (1964) became highly regarded and a classic almost as soon as it was published. It centres intensely on the life of Moses Herzog, a Jewish intellectual who is driven close to the verge of breakdown by the adultery of his second wife with his close friend. He writes letters to famous people, both living and dead – Spinoza, Nietzsche, Winston Churchill, and the President of the USA – giving them a piece of his mind and asking their advice about how to live. The novel begins with a statement which sets the tone for everything that follows: “If I am going out of my mind, it’s all right with me, thought Moses Herzog”.

Herzog (1964) became highly regarded and a classic almost as soon as it was published. It centres intensely on the life of Moses Herzog, a Jewish intellectual who is driven close to the verge of breakdown by the adultery of his second wife with his close friend. He writes letters to famous people, both living and dead – Spinoza, Nietzsche, Winston Churchill, and the President of the USA – giving them a piece of his mind and asking their advice about how to live. The novel begins with a statement which sets the tone for everything that follows: “If I am going out of my mind, it’s all right with me, thought Moses Herzog”. Humboldt’s Gift (1974) traces the life and memories of writer Charlie Citrine as he reflects on the influence of his boyhood friend and mentor, Humboldt. This character is based loosely upon Delmore Schwartz, the Jewish poet and short story writer whose early promise was never fulfilled. He descended into alcoholism and poverty, and died in a cheap hotel room, creating the modern version of the myth of the ‘doomed poet’. The novel deals with the ‘gift’ for aesthetic appreciation he passes on to his close friend Charlie, the narrator of the novel.

Humboldt’s Gift (1974) traces the life and memories of writer Charlie Citrine as he reflects on the influence of his boyhood friend and mentor, Humboldt. This character is based loosely upon Delmore Schwartz, the Jewish poet and short story writer whose early promise was never fulfilled. He descended into alcoholism and poverty, and died in a cheap hotel room, creating the modern version of the myth of the ‘doomed poet’. The novel deals with the ‘gift’ for aesthetic appreciation he passes on to his close friend Charlie, the narrator of the novel. Ravelstein (2000) is something of a double portrait. Abe Ravelstein, a mega-successful Jewish academic realises that he might be dying. He invites his friend Chick to write an biographical study of him. What we get is a not-so-thinly disguised portrait of the critic Allan Bloom written by a character who has had all the brushes with life which Bellow experienced in his own: near-death illness, late-life divorce, and happiness with a new wife. Since his death, it has become a lot clearer just how much of his own life Bellow put into his fiction.

Ravelstein (2000) is something of a double portrait. Abe Ravelstein, a mega-successful Jewish academic realises that he might be dying. He invites his friend Chick to write an biographical study of him. What we get is a not-so-thinly disguised portrait of the critic Allan Bloom written by a character who has had all the brushes with life which Bellow experienced in his own: near-death illness, late-life divorce, and happiness with a new wife. Since his death, it has become a lot clearer just how much of his own life Bellow put into his fiction.

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories