part one of the definitive biography

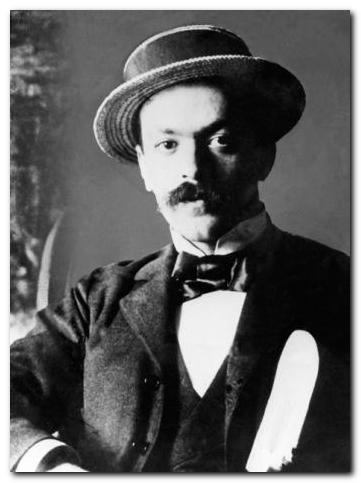

This is the currently definitive biography of Igor Stravinsky – master of European modernism whom many consider to be the greatest composer of the twentieth century. It’s a consummate and magisterial piece of work – superbly referenced and annotated; and just about every claim made within it is backed up with evidence. The notes to the text itself run to 113 pages.

Stephen Walsh begins by clearing the ground between himself and Robert Craft – the man who made himself Stravinsky’s amanuensis, secretary, helpmate, and collaborator towards the end of his life. Craft wanted to control the Stravinsky estate (including the money) as well as his critical reputation, but Walsh is having none of that. He insists on factual accuracy, backed up with hard evidence.

Yet even though it’s quite clear that he knows everything there is to know about the details of Stravinsky’s life, and can justify every claim with a fully referenced source, he has problems constructing a logical and readable narrative of the composer’s life. For instance Stravinsky’s brother Roman dies three times within as many short chapters at the start of the book, and Stravinsky is abruptly announced to be twenty years old and has completed his first piece of music on page fifty. Most of the previous forty-nine have been devoted to describing the Russian countryside.

Yet even though it’s quite clear that he knows everything there is to know about the details of Stravinsky’s life, and can justify every claim with a fully referenced source, he has problems constructing a logical and readable narrative of the composer’s life. For instance Stravinsky’s brother Roman dies three times within as many short chapters at the start of the book, and Stravinsky is abruptly announced to be twenty years old and has completed his first piece of music on page fifty. Most of the previous forty-nine have been devoted to describing the Russian countryside.

Walsh is exceptionally good at recreating the social and historical context in which Stravinsky was raised – from the lack of sanitation in late nineteenth-century Petersburg to the fact that the composer didn’t even go to school until he was nearly eleven.

The story of Stravinsky’s life is already fairly well known, so what does Walsh offer that’s new? Well, quite apart from his claim to accuracy in interpreting textual evidence, it’s quite clear that he is an authority on Russian cultural history. Every time a friend, relative, or acquaintance enters the story, his narrative swells out for pages on end with their biographical details – to the extent that (especially in the earlier part of the book) Stravinsky himself becomes a indistinct figure, hovering indistinctly like some half-forgotten ghost.

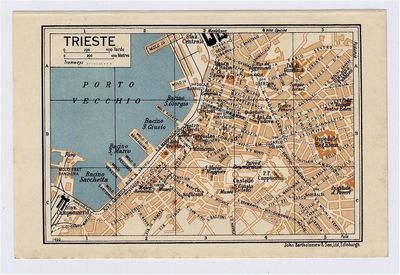

This is a feature of Walsh’s approach which you would expect to diminish as Stravinsky becomes more successful – largely because he is endlessly on the move from one city and country to another – Petersburg, Brittany, Switzerland, Paris, Cote d’Azur. This is the material of a biographer’s dream. But Walsh is more interested in scouring correspondence to apportion exact responsibility for the plot development of the early masterpieces (Firebird, Petrushka, The Rite of Spring) The composer’s dramatic private life is left relatively unexamined – despite his meeting with such luminaries as Debussy, Ravel, Proust, Schoenberg, and Manuel de Falla.

And this avoidance of the personal has some serious repercussions. When Diaghilev throws an enormous tantrum on hearing of Nijinsky’s marriage, Walsh still can’t bring himself to mention the fact that they had been lovers. Diaghilev shunned The Rite of Spring because of its close connection with his ex-favourite – and this immediately affected Stravinsky’s ability to earn a living from its success – for a personal, not a musical reason.

But we do gain benefits from his thoroughness, as well as having to endure its longeurs. On Stravinsky’s first visit to Spain, an affair with the ballerina Lydia Lopukhova is followed up biographically to record that she later married Diaghilev’s financial manager, and then later after eloping from London with a Russian general, she eventually married John Maynard Keynes.

Another thing which emerges instructively from all the background commentary on Stravinsky’s work (and that of his collaborators) is what utter rubbish many of the so-called critics wrote about the music. Jacques Riviere on the Rite of Spring for instance:

The Rite of Spring … has no juice to dull its brilliance, no cookery to rearrange or spoil its contours. It is not a “work of art”, with all the usual palaver. Nothing blurred, nothing reduced by shadows; no veils or poetic softenings; no trace of atmosphere. The work is whole and untreated…

As he becomes more successful, the 1920s are passed in the swirl of a quasi-bohemian, quasi-aristocratic milieu. Oedipus Rex was a collaboration with opium-addicted Jean Cocteau, whose detoxification cures were paid for by Coco Chanel, with whom Stravinsky had a brief affair.

But the dominant figure in this first volume is certainly Diaghilev, with whom Stravinsky collaborated on almost all his early major works. The two men had their differences, especially over money; but they respected each other as artists, and seemed to bring out the best in each other.

The other problematic leitmotif in Stravinsky’s life is that of copyright, which had not been internationally agreed at the time of his early works. There were also very complex arrangements whereby some people ‘owned’ works because they had paid a commissioning fee, and others held the rights to performances for a limited period. This resulted in erratic income for the composer – though a man who could buy a large chauffer-driven automobile in the 1920s was not in financial difficulties.

Stravinsky also had the expense of keeping two ‘families’. For his life was divided permanently between his lover Vera Sudeykina, with whom he lived in Paris and took on concert tours, and Katya, his wife and the mother of his four children, whom he left at home and visited when required.

It’s interesting to note how fond Stravinsky was of any technical developments which would assist him in both making a record of his own work and exploring the possibilities of new sounds. He made piano rolls, bought a player-piano, learnt to play the cimbalom, and eagerly recorded his work on both mechanical and electrical equipment.

Serious musicologists will be glad to learn that Walsh puts a lot of effort into tracing the developments in Stravinsky’s musical style. This goes (in this volume) from the expressive force of the Rite to the neo-classicism of Apollo. This is done in an all-round manner by looking at the original ‘idea’ (often the result of a commission) then the musical material from which he took his inspiration, through to the actual conditions (and possible limitations) which surrounded the first performance.

Despite some of the negative effects of Walsh’s writing, I found this a fascinating account of the artist and a well-informed glimpse into a rich period of cultural history. Volume one ends in 1934 with the Nazis in the ascendant and Stravinsky sharing musical chit-chat with Mussolini, for who he had a high regard. In this climactic year Stravinsky took out French citizenship and moved his entire extended family into a fifteen-room apartment near the Place de la Concorde – in the arrondissement next to his lover Vera. Stravinsky’s main worry about this proximity was that his eighty-year-old mother should not find out about his not-so-secret other life.

![]() See part two of this biography

See part two of this biography

© Roy Johnson 2009

Stephen Walsh, Igor Stravinsky – A Creative Spring: Russia and France 1882-1934, London: Pimlico, 2002, pp.696, ISBN: 1845952219

More on music

More on media

More on lifestyle

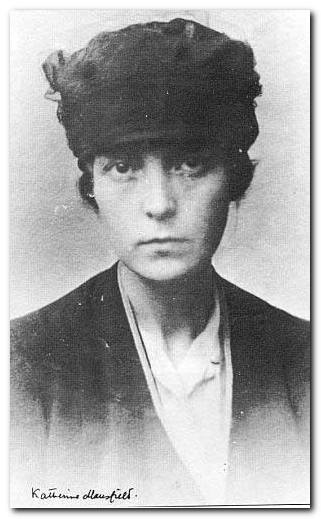

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures. Maynard Keynes was born and raised in Cambridge, the seat of intellectual and political power, even more so then than now. He was also educated at Eaton – and yet his social origins were quite modest. One grandfather John Brown was an apprentice printer from Lancashire who later graduated from Owens College (Manchester University) and went on to become a preacher. The other grandfather made his fortune from cultivating dahlias and roses. His father John Neville Keynes went to University College London and then to Cambridge where he briefly became a lecturer and where he met Keynes’ mother, who was a student at Newnham Hall. However, Neville (the family used their middle names) did not feel suited to the life of a don, and became instead an administrator in the examinations board.

Maynard Keynes was born and raised in Cambridge, the seat of intellectual and political power, even more so then than now. He was also educated at Eaton – and yet his social origins were quite modest. One grandfather John Brown was an apprentice printer from Lancashire who later graduated from Owens College (Manchester University) and went on to become a preacher. The other grandfather made his fortune from cultivating dahlias and roses. His father John Neville Keynes went to University College London and then to Cambridge where he briefly became a lecturer and where he met Keynes’ mother, who was a student at Newnham Hall. However, Neville (the family used their middle names) did not feel suited to the life of a don, and became instead an administrator in the examinations board. At this point Keynes’s personal life became quite complex, with cross-connections that have since made the Bloomsbury Group famous. He was a friend and ex-lover of Lytton Strachey, who had fallen in love with his own cousin

At this point Keynes’s personal life became quite complex, with cross-connections that have since made the Bloomsbury Group famous. He was a friend and ex-lover of Lytton Strachey, who had fallen in love with his own cousin  However, this mixing with Bloomsbury also brought him personal distress. Duncan Grant started an affair with

However, this mixing with Bloomsbury also brought him personal distress. Duncan Grant started an affair with  In the early 1920s Keynes was actively involved in solving the lingering problem of post-war reparations, something in which he participated as an economist, a government advisor, and (secretly) as an unofficial diplomatist. At the same time he formed a group to take over the liberal journal Nation and Athenaeum of which he made Leonard Woolf the editor. Then, in the midst of all this, he surprised everyone by falling in love with the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, who stayed in England when Diaghilev de-camped to Monte Carlo.

In the early 1920s Keynes was actively involved in solving the lingering problem of post-war reparations, something in which he participated as an economist, a government advisor, and (secretly) as an unofficial diplomatist. At the same time he formed a group to take over the liberal journal Nation and Athenaeum of which he made Leonard Woolf the editor. Then, in the midst of all this, he surprised everyone by falling in love with the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, who stayed in England when Diaghilev de-camped to Monte Carlo.