tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

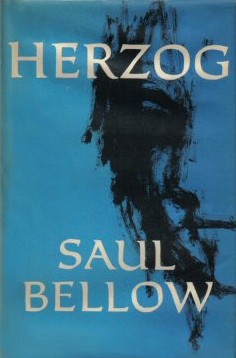

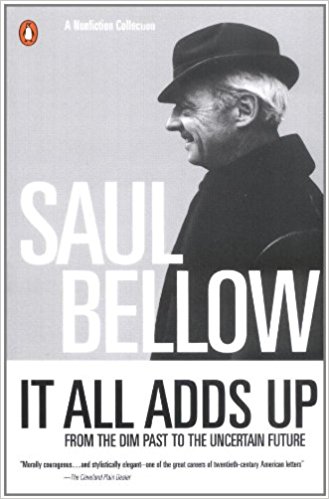

Herzog (1964) won several literary prizes when it was first published, and was voted one of the best 100 novels written in English by Time magazine. As in the case of other major novels by Saul Bellow, it has a strong biographical basis. Herzog and Bellow were both Jewish academics and intellectuals from Chicago; they were the same age; and both had been twice married and divorced. Most tellingly, both their second wives had been involved in affairs with a husband’s best friend.

The main feature of the novel which makes it very entertaining is the series of letters that Herzog writes to famous people, living and dead. He shares his hopes and fears with people he has never met (including God) and discusses abstract concepts with philosophers who were writing in the eighteenth century.

Herzog – critical commentary

Historical note

When it first appeared in 1964 Herzog was received generally as a comic novel – a knockabout story of a character who was disoriented and wrote letters to well-known political and historical figures. Herzog interrogates his relatives and friends, gives advice to famous politicians, and poses philosophic questions to writers who have been dead for centuries.

Bellow had invented earlier a new kind of free-wheeling narrator in his previous novel The Adventures of Augie March (1954) and he was perceived as a fresh voice from the well-educated streets of Chicago and New York. His novels offered ideas, rumbustious events plucked from modern American life, and lots of linguistic fun. He seemed willing to take an off-beat, radical approach to characterisation and his subject matter. As his protagonist Moses Herzog announces in the opening paragraph: ‘If I am out of my mind, it’s all right with me’.

But reading Herzog half a century later, it seems that the sense of fun has receded. Now it is quite clear that the novel was written out of a very painful experience of marital breakdown and the bitter consequences of divorce.

Bellow was also carving out what was to become the central issue of his later novels – the history of the Jewish immigrant experience in America. In Herzog he covers two generations – the first who arrived from Russia (and elsewhere) and endured poverty and hardships in order to make a new life for themselves in the New World. Then the second generation, who stood on their shoulders and had the choice of continuing the family’s Jewish traditions, or becoming fully assimilated as Americans

Biography

It’s quite clear on even the most cursory reading of this novel that it was based upon deeply felt personal experiences. Bellow makes very little effort to conceal the proximity of events in his narrative to the details of his own biography. Herzog is born in Canada of Russian Jewish immigrants, lives in Chicago, and becomes an academic, specialising in literature and intellectual history – exactly the same as Bellow himself.

Bellow had been married twice when he wrote the novel. He had also recently discovered that his second wife Sondra had been having an affair with his best friend Jack Ludwig. Many novelists use elements from their own lives as materials for their fiction. The question is – how does this affect our understanding and interpretation of their work?

The first thing to say is that novelists are under no obligation to be truthful, fair, accurate, or even-handed in their use of this autobiographical material. Fiction has its own rules, and novelists are at liberty to use their life experiences in any way they wish.

But the corollary for the reader is that the fictional results must not be taken as an accurate account of the writer’s life. Just as good biography should be an accurate account of events, and should not include fictional inventions, good fiction should not be taken as the base material for biographical interpretation.

However, it has to be said that this is a somewhat purist approach to literary interpretation. Most literary critics and commentators will use any information they have to pass judgement on writers and their work. Many people might argue that Bellow’s depiction of the character Madeleine reveals his deep-seated misogyny and is a form of fictional ‘revenge’ for the personal affront he felt from his wife’s betrayal.

The same could be said for the character of Valentine Gersbach – though interestingly, there is much less venom heaped upon him, and in general he is depicted as a more benign character. It is Madeleine who Herzog thinks he would like to murder, not his love rival Gersbach.

The letters

At the beginning of the novel we are led to believe that Herzog is writing letters to friends and relatives about the break-up of his marriage. Then as he becomes more desperate he starts writing to public figures and historical philosophers, many of whom died centuries earlier.

Then gradually it becomes clear that the letters are never posted, and finally that they are not written at all. The ‘letters’ are Herzog’s internal dialogue with friends, family, and ‘the dead’ – as well as a form of critical dialogue with the intellectual history of which he feels a part. In other words the ‘letters’ function as a metaphor. They represent one of the three strands of the narrative which focus attention relentlessly on Herzog and his state of mind:

- third person omniscient narrator

- Herzog as first person narrator

- Herzog’s letters to others

Herzog’s actions, thoughts, and feelings are sometimes presented by a third person omniscient narrator, but Saul Bellow seamlessly blends this presentation of events with Herzog’s first person account of his experiences, and even his commentary on his own thoughts. These two narrative strands are then supplemented by the ‘thought letters’ – which are presented in the printed text by italics

Philosophy

The principal weakness in Herzog as in many of Bellow’s other novels, is the long-winded ‘philosophising’ that goes on in the protagonist’s search for a resolution to the contradictions he finds in his life. To these speculations he also adds what have been called ‘reading lists’.

These are long references to western writers and philosophers by which Bellow suggests he has a detailed knowledge of political thinking from Greco-Roman classics, through Renaissance thought, to Hegel, Marx, Heidegger, and anyone else worth mentioning in the twentieth century These names are offered up in a thick porridge of vague abstractions – a process which adds up to no more than a form of self-indulgent intellectual name-dropping. Bellow is far more successful when he sticks to deadpan (and very typically American) humour:

I am diligent. I work at it and show steady improvement. I expect to be in great shape on my deathbed.

Will never understand what women want. What do they want? They eat green salad and drink human blood.

Herzog

There is something of an embarrassment for the reader in dealing with Herzog as the protagonist – who is quite clearly a cipher for Saul Bellow and his concerns. Herzog is being offered as something of a loveable rogue – a man who has warm ties to his Jewish immigrant family and its traditions, who has been badly treated by his second wife and friends such as Gersbach and Himmelstein. He is also in the tradition of the holy fool – the naive intellectual with his mind on higher matters who repeatedly makes bad decisions on his own behalf and does absurd things such as painting a piano green.

But by the same token we can say that he is self-obsessed; he is erotically incontinent; he has established his home with money inherited from his father, and spends most of the novel living off his brothers; and it’s even possible to argue that he is something of an intellectual snob. He certainly spends lots of mental energy railing against the beautiful but clever woman who has deceived him (Madeleine). Yet he discounts and feels sceptical about the beautiful and loving, but not-so-clever woman whom he believes wants to ‘snare’ him (Ramona).

There is no shortage of self-criticism in Bellow’s characterisation of Herzog, but it’s also impossible to escape a certain sense of smugness and self-regard, even if his soul-searching is wrapped up in multiple references to western philosophers – or maybe even because it is.

Kafka

There are distinct elements of Franz Kafka at work in Herzog. Both writers feature protagonists in search of justice who at every turn of events seem to make their own predicaments worse. They both create heroes with friends who protest their support but then undermine or betray the protagonist in some way. Both Kafka and Bellow explore the dilemmas of characters who seek to maintain high ethical ideals in a world founded on lying, greed, and deception – characters whose efforts often result in comic misunderstandings or grotesque embarrassment.

Herzog gives himself up to shysters such as Sandor Himmelstein, but when offered genuine sympathy and comforting friendship from Phoebe Sissler and her husband, he runs away from their kindness, thinking it is a ‘mistake’. He is full of contradictions – and he knows it.

Herzog is also like a Kafka figure in that many of his problems have been brought on because of his erotic behaviour. He has had two wives, and chosen for the second a woman who has validated all his worst fears about entrapment and persecution. Madeleine is the vagina dentata writ large. She has stripped him of his material assets and humiliated him sexually by adultery with his best friend. Yet when he is offered comfort and sexual healing by his very attractive lover Ramona, what does he do but run away from her. All this is very neurotic behaviour.

Even his struggles with society at a political level have elements of what we now call the ‘Kafkaesque’. Franz Kafka’s protagonists struggle to understand the byzantine processes of the powers that control them (largely the bureaucracy of the Hapsburg empire). Similarly, Moses grapples hopelessly as an individual with the complexities of a society controlled partly by democracy, and partly by a ‘political machine’ which includes graft, corruption, vote-fixing, and gangsters. Even his own father was a bootlegger.

Moses is also grappling intellectually with issues of the western European philosophic traditions and their inability to grant him some sort of overarching understanding of the modern society in which he lives. He is lost in a world of Locke, Hume, Nietzsche, and Heidegger (so we are asked to believe) but meanwhile he doesn’t have the common sense to know that his wife is having an affair with his best friend.

Moses claims to be seeking resolution and peace of mind in a world full of conflicts – yet he positively embraces difficulties and hardship, even feeling the loss of them when they are not there. And this neurotic behaviour is expressed in distinctly Kafkaesque language and metaphors, including one of Kafka’s favourites – the vulture:

When a man’s breast feels like a cage from which all the dark birds have flown – he is free, he is light. And he longs to have his vultures back again. He wants his customary struggles, his nameless, empty works, his anger, his afflictions, and his sins.

Reflecting on the level of antipathy Herzog feels towards his ex-wife Madeleine who has betrayed him with his best friend, Bellow coins an epigram that could come straight out of Kafka’s diaries or notebooks:

It’s fascinating that hatred should be so personal as to be almost loving. The knife and the wound, aching for each other.

Herzog – study resources

![]() Herzog – Penguin – Amazon UK

Herzog – Penguin – Amazon UK

![]() Herzog – Penguin – Amazon US

Herzog – Penguin – Amazon US

![]() Herzog – Library of America – Amazon UK

Herzog – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Herzog – Library of America – Amazon US

Herzog – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() Saul Bellow – Collected Stories – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Saul Bellow – Collected Stories – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Saul; Bellow – Collected Stories – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Saul; Bellow – Collected Stories – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Saul Bellow (Modern Critical Views) – essays and studies – Amz UK

Saul Bellow (Modern Critical Views) – essays and studies – Amz UK

![]() Saul Bellow (Modern Critical Views) – essays and studies – Amz US

Saul Bellow (Modern Critical Views) – essays and studies – Amz US

Cambridge Companion to Saul Bellow – Amazon UK

Herzog – plot summary

Moses Herzog is a Jewish academic who has moved from a large house in Berkshire to Chicago at the behest of Madeleine, his second wife. When Madeleine suddenly wants a divorce he leaves his home and his job and moves back to New York. City where he starts compulsively writing to people – both living and dead.

He consults a doctor, but there is nothing physically wrong with him. His lover Ramona invites him to take a holiday in her house, but fearing ‘commitment’ he travels instead to stay with some friends at Martha’s Vineyard.

He buys sporty summer clothes and thinks about Wanda, a married woman with whom he had an affair on a trip to Poland. He also reflects on relations with his mother in law and discussions about her with Simkin, his divorce lawyer.

On the train he thinks over Madeleine’s affair with his friend Gersbach and ‘writes’ to her aunt Zelda who has conspired in his deception.

His friend the zoologist Lucas Asphalter reveals Madeleine’s adultery with Gersbach. Herzog recalls analysis under Dr Edvig which spills over to include Madeleine. She becomes ill, goes on wild spending sprees, and finally attacks Herzog physically.

Herzog turns for help to his best friend Gersbach (with whom Madeleine is having the affair). Gersbach lectures him on dignity and suffering. Herzog writes letters to public figures, offering them advice.

He recalls a discussion between Madeleine and his old friend Schapiro about Russian culture. His letter to Schapiro is about political philosophy, but he also complains that Madeleine has been trying to take his place in the academic world. He borrows money from his brother Shura.

After the split with Madeleine, Herzog goes to stay with old friend Sandor Himmelstein, whose attitude becomes more and more critical. Sandor even tries to sell him some insurance., then hits him hard with Jewish sentimentalism.

Herzog arrives chez Libbie and her new husband Sissler in Martha’s Vineyard. They welcome him very warmly, but he immediately thinks the visit is a mistake. He leaves them an apologetic note and flies back home.

In New York he receives news of problems with his daughter who is living with Madeleine and Gersbach. He thinks back to a period when he was married to Daisy, involved with Japanese girl Sono, and preparing to leave them both for Madeleine.

In the early days of his relationship with Madeleine, she is a recent convert to Catholicism and full of guilt about adultery. But she gives up the Church, they get married, and go to live in the country, with the Gersbachs as neighbours. Madeleine squanders money, and they start to argue.

He looks back nostalgically on his first marriage to Daisy and reflects on his Jewish childhood. His father was a first generation immigrant and a small time bootlegger. The family have a drunken lodger and relatives who die back in Russia. Moses affectionately recalls the poverty yet warmth of the family in its early immigrant years.

Ramona phones with an invitation to dinner which he reluctantly accepts. He drifts into writing letters on political philosophy and drafting a proposal for an essay on ‘transcendence’. Then he recalls his relationship with Sono, his Japanese lover. She warns him against Madeleine, and in his imaginary letter to her he admits that she was right.

Ramona showers him with affection and understanding – but deep down he is reluctant. They discuss at length his problems with Madeleine and Gersbach.

He consults lawyer Harvey Simkin who urges him to take Madeleine and Gersbach to court and seek revenge. Herzog visits a courtroom where he witnesses a trial for child murder and he has a form of mild heart attack.

He flies to Chicago and visits his parents’ old house, recalling an argument with his father. Whilst there he secretly retrieves his father’s old pistol.

Fearing his own daughter might be at risk, he drives to Madeleine’s house with murder in mind. But when he sees Gersbackh bathing June, he cannot pull the trigger. He visits Gersbach’s wife Phoebe instead. She is in denial and claims that Gersbach is still living with her

He goes to stay with Lucas Asphalter with whom he discusses attitudes to death. He takes his daughter June out for the day, but becomes involved in a traffic accident. The police arrest him for carrying a loaded gun. Madeleine arrives at the police station, full of hostility. His brother Will is called to post bail.

After borrowing money from Will, he goes to his abandoned house in the Berkshires and sinks into eccentric behaviour. He begins a new series of letters to his psychiatrist, to Nietzsche, and to God.

His brother Will arrives, sees that Herzog is cracking up, and recommends medical care and rest. Herzog refuses and plans to invite his son Marco to stay.

Ramona visits a nearby town. He goes over, invites her to dinner, and begins cleaning up the house. He also finally decides to stop writing letters.

Herzog – principal characters

| Moses Herzog | a confused academic dreamer with marital problems |

| Madeleine | his second wife, a beautiful and clever ball-breaker |

| Valentine Gersbach | his neighbour and best friend, who has an affair with Madeleine |

| Dr Edvig | psycho-analyst to both Herzog and Madeleine |

| Ramona Donsell | a flower shop owner, Herzog’s attractive lover |

| Fritz Pointmueller | Madeleine’s father, a theatrical impresario |

| Trennie Pointmueller | his wife, Madeleine’s mother |

| Harvey Simkin | Herzog’s divorce lawyer |

| Lucas Asphalter | a zoologist and boyhood friend of Herzog |

| Schapiro | an old friend of Herzog |

| Sandor Himmelstein | a Chicago lawyer and friend of Herzog |

© Roy Johnson 2017

More on Saul Bellow

More on the novella

More on short stories

Twentieth century literature

The Longest Journey

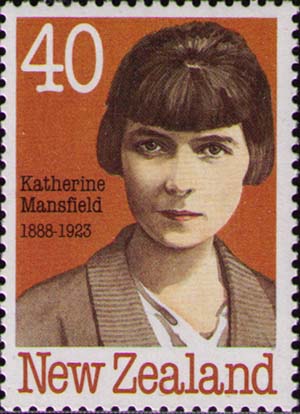

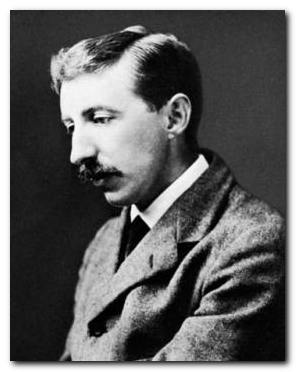

The Longest Journey A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

The Cambridge Companion to Proust

The Cambridge Companion to Proust Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando

Orlando Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf