characters, resources, video, translations

There’s no doubt about it: if you’re going to tackle In Search of Lost Time (or Remembrance of Things Past as it is also known) you need to be in good intellectual shape. The sentences are long, the paragraphs are huge, and at a million and a half words his great novel is one of the longest ever.

But it can be done – and the benefits are enormous. Proust delivers gems on every page. He is of course celebrated for his psychological insights. His characters live and breathe in a way which makes you feel they become your personal friends. Don’t expect plot, suspense, or even story in a conventional sense. This modern classic is one of characters circling around each other in a way which depicts an entire world of upper-class fin de circle France before and shortly after the First World War.

However, the greatest depths he offers are in the form of profound reflections on some of the most important issues any novelist can approach – love, desire, memory, time, and death. These are written in the form of extended aphorisms, embedded as part of his narrative in such a way that you will hardly be aware where one ends and the other begins.

Other people are, as a rule, so immaterial to us that, when we have entrusted to any one of them the power to cause so much suffering or happiness to ourselves, that person seems at once to belong to a different universe, is surrounded with poetry, makes of our lives a vast expanse, quick with sensation, on which that person and ourselves are ever more or less in contact.

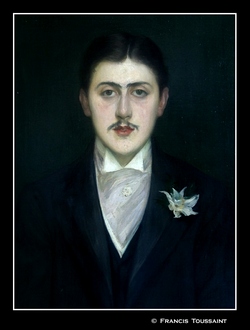

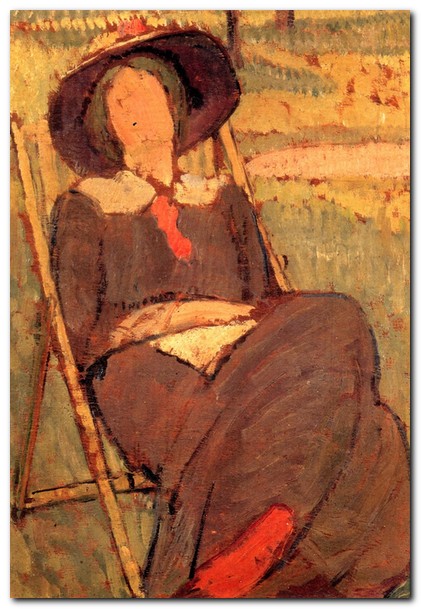

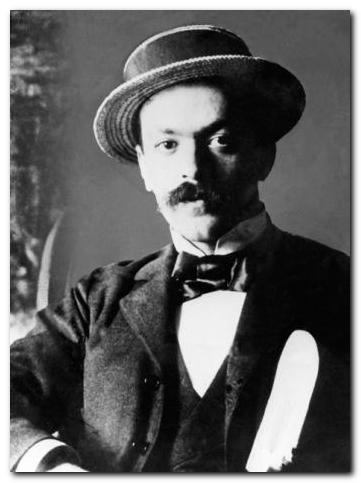

Marcel Proust – portrait by Jaques Emil Blanche

Study resources

![]() In Search of Lost Time – 6 volume boxed set (Modern Library) – UK

In Search of Lost Time – 6 volume boxed set (Modern Library) – UK

![]() In Search of Lost Time – 6 volume boxed set (Modern Library) – US

In Search of Lost Time – 6 volume boxed set (Modern Library) – US

![]() In Search of Lost Time – 4 volume boxed set (Everyman’s Library) – UK

In Search of Lost Time – 4 volume boxed set (Everyman’s Library) – UK

![]() In Search of Lost Time – 4 volume boxed set (Everyman’s Library) – US

In Search of Lost Time – 4 volume boxed set (Everyman’s Library) – US

![]() Proust: an illustrated life – short biography with period photos

Proust: an illustrated life – short biography with period photos

![]() Proust’s life and works – a detailed chronology

Proust’s life and works – a detailed chronology

![]() A Reader’s Guide to Proust – Amazon UK

A Reader’s Guide to Proust – Amazon UK

![]() Proust Website – general resources

Proust Website – general resources

![]() Proust’s In Search of Lost Time – web site with videos

Proust’s In Search of Lost Time – web site with videos

![]() Reading Proust – various translations compared

Reading Proust – various translations compared

![]() Swann’s Way – an essay on translations

Swann’s Way – an essay on translations

![]() Swann in Love – 1984 DVD adaptation in English – Amazon UK

Swann in Love – 1984 DVD adaptation in English – Amazon UK

![]() Time Regained – 1999 DVD adaptation (English subtitles) – Amazon UK

Time Regained – 1999 DVD adaptation (English subtitles) – Amazon UK

![]() Monsieur Proust – the housekeeper’s memoirs – Amazon UK

Monsieur Proust – the housekeeper’s memoirs – Amazon UK

![]() Marcel Proust at Wikipedia – biographical notes, web links

Marcel Proust at Wikipedia – biographical notes, web links

![]() Marcel Proust at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Marcel Proust at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Proust in the original French

![]() A la recherche du temps perdu – 10 volumes, illustrated (Kindle) pp.2911 – £2.22 – Amazon UK

A la recherche du temps perdu – 10 volumes, illustrated (Kindle) pp.2911 – £2.22 – Amazon UK

![]() Oeuvres complètes de Marcel Proust – Illustrated, with biography and criticisim (Kindle) pp.4100 – £1.32 – Amazon UK

Oeuvres complètes de Marcel Proust – Illustrated, with biography and criticisim (Kindle) pp.4100 – £1.32 – Amazon UK

Principal characters

| Marcel | the outer narrator of the novel |

| Bathilde Amedee | the narrator’s grandmother |

| Francoise | the narrator’s faithful maid |

| Baron de Charlus | an aristocratic dandy and gay aesthete |

| Duchesse de Guermantes | the toast of Parisian high society |

| Robert de Saint-Loup | army officer and narrator’s best friend |

| Charles Swann | a friend of the narrator’s family |

| Odette de Crecy | a beautiful Parisian courtesan |

| Gilberte Swann | the daughter of Swann and Odette |

| Elstir | a famous painter |

| Bergotte | a well-known writer |

| Vinteuil | an obscure but talented musician |

| Berma | a famous actress |

| Charles Morel | a gifted violinist, patronised by Charlus |

| Albertine Simonet | an orphan with whom the narrator has a romance |

| Madame Verdurin | a rapacious social-climber |

In Search of Lost Time – film adaptation

Catherine Deneuve, John Malkovich

Further reading

![]() Aciman, André (2004) The Proust Project. New York Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Aciman, André (2004) The Proust Project. New York Farrar, Straus and Giroux

![]() Albaret, Céleste (Barbara Bray, trans.) (2003) Monsieur Proust. The New York Review of Books

Albaret, Céleste (Barbara Bray, trans.) (2003) Monsieur Proust. The New York Review of Books

![]() Alexander, Patrick (2009) Marcel Proust’s Search for Lost Time. Vintage Books, New York.

Alexander, Patrick (2009) Marcel Proust’s Search for Lost Time. Vintage Books, New York.

![]() Bernard, Anne-Marie (2002) The World of Proust, as seen by Paul Nadar. Cambridge: MIT Press

Bernard, Anne-Marie (2002) The World of Proust, as seen by Paul Nadar. Cambridge: MIT Press

![]() Bloom, Harold. (2003) Marcel Proust, Chelsea House.

Bloom, Harold. (2003) Marcel Proust, Chelsea House.

![]() Carter, William C. (2000) Marcel Proust: A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press

Carter, William C. (2000) Marcel Proust: A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press

![]() Caws, Mary Ann. (2003) Marcel Proust: Illustrated Lives. Overlook Press.

Caws, Mary Ann. (2003) Marcel Proust: Illustrated Lives. Overlook Press.

![]() Curtiss, Mina. (2006) The Letters of Marcel Proust Turtle Point Press.

Curtiss, Mina. (2006) The Letters of Marcel Proust Turtle Point Press.

![]() Davenport-Hines, Richard (2006) Proust at the Majestic. Bloomsbury

Davenport-Hines, Richard (2006) Proust at the Majestic. Bloomsbury

![]() De Botton, Alain (1998) How Proust Can Change Your Life. New York: Vintage Books

De Botton, Alain (1998) How Proust Can Change Your Life. New York: Vintage Books

![]() Deleuze, Gilles (2004) Proust and Signs: The Complete Text. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Deleuze, Gilles (2004) Proust and Signs: The Complete Text. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

![]() Painter, George D (1959) Marcel Proust A Biography Vols. 1 & 2. London: Chatto & Windus

Painter, George D (1959) Marcel Proust A Biography Vols. 1 & 2. London: Chatto & Windus

![]() Shattuck, Roger (1963) Proust’s Binoculars: A Study of Memory, Time, and Recognition in À la recherche du temps perdu. New York: Random House

Shattuck, Roger (1963) Proust’s Binoculars: A Study of Memory, Time, and Recognition in À la recherche du temps perdu. New York: Random House

![]() Shattuck, Roger (2000) Proust’s Way: A Field Guide To In Search of Lost Time, W. W. Norton

Shattuck, Roger (2000) Proust’s Way: A Field Guide To In Search of Lost Time, W. W. Norton

![]() Tadié, Jean-Yves: Marcel Proust: A Life. Viking, New York, 2000

Tadié, Jean-Yves: Marcel Proust: A Life. Viking, New York, 2000

![]() White, Edmund (1998) Marcel Proust: A Life. New York: Viking Books

White, Edmund (1998) Marcel Proust: A Life. New York: Viking Books

Proust’s writing – I

Mont Blanc – Marcel Proust special edition

Don’t let this glamorous fountain pen deceive you. Marcel Proust’s writing instruments and his notebooks were quite humble. He used Sergent-Major nibs and pen holder which were the cheapest of their kind. For paper, he used the common French school children’s exercise notebooks which he purchased in bulk.

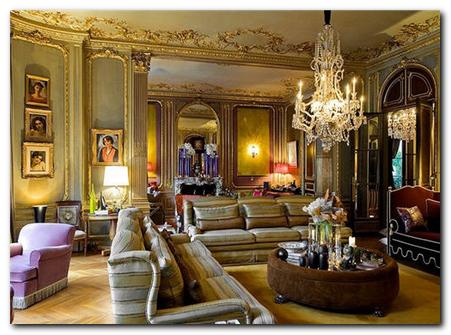

Parisian interior – La belle epoque

Proust’s writing – II

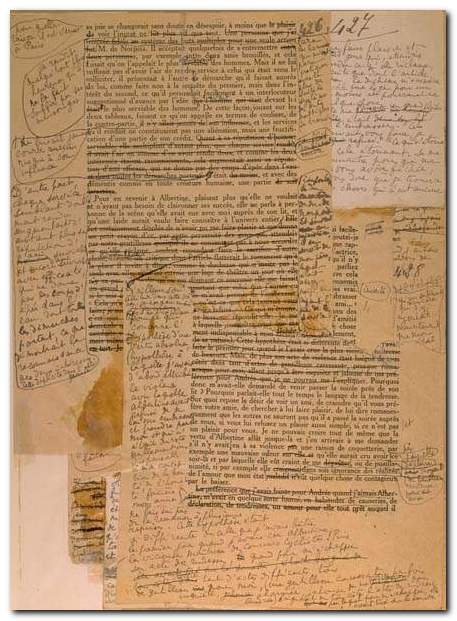

Revisions to a typescript

Proust’s method of composition was highly accretive. He wrote primarily in children’s exercise books, but his first drafts were supplemented by countless additions, revisions, and extensions of thought which he scribbled down on any paper which came to hand.

Envelopes, magazine covers, scraps of paper of different length and format were glued into the exercise books or joined together to form long scrolls sometimes two metres long.

This process also continued when proofs of his manuscript came back from the printer. This was a habit very similar to that of his illustrious predecessor Balzac. As Terrence Kilmartin observes:

The margins of proofs and typescripts were covered with scribbled corrections and insertions, often overflowing on to additional sheets which were glued to the galleys or to one another to form interminable strips – what Françoise in the novel calls the narrator’s paperoles. The unravelling and deciphering of these copious additions cannot have been an enviable task for editors and printers.

In Search of Lost Time – editions

Click the jacket covers for further details at Amazon UK

Which translation should you read? In English there are three options currently in print. My favourite is the oldest by C.K. Scott Moncrieff. It was the first to appear as the original volumes were published, and it even had Proust’s own blessing. Although it is based on a version of the French original which was not complete, it has a charm all of its own. It is this version which gave the novel its alternative title Remembrance of Things Past when Scott Moncrieff chose a quotation from Shakespeare’s Sonnet XXX, rather than a literal translation of the original:

Which translation should you read? In English there are three options currently in print. My favourite is the oldest by C.K. Scott Moncrieff. It was the first to appear as the original volumes were published, and it even had Proust’s own blessing. Although it is based on a version of the French original which was not complete, it has a charm all of its own. It is this version which gave the novel its alternative title Remembrance of Things Past when Scott Moncrieff chose a quotation from Shakespeare’s Sonnet XXX, rather than a literal translation of the original:

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought,

I summon up remembrance of things past

The jacket cover illustrated here is that of the old Chatto and Windus edition which was presented in twelve volumes. Snap these up if you see them, but in the meantime this translation is available from Penguin books.

The second option is an edition which is based on the Scott Moncrieff original translation, but which was revised and re-translated by Terrence Kilmartin in the 1990s. This version is also informed by updated versions of the original text in French, including new material which has come to light since the author’s death. Kilmartin’s work was then itself edited by D.J.Enright

The second option is an edition which is based on the Scott Moncrieff original translation, but which was revised and re-translated by Terrence Kilmartin in the 1990s. This version is also informed by updated versions of the original text in French, including new material which has come to light since the author’s death. Kilmartin’s work was then itself edited by D.J.Enright

So this version comes to us with a guarantee of completeness and accuracy, but with the traces of three different translators’ hands since the original work. Each volume contains its own notes, addenda, and a synopsis, so readers new to Proust can feel supported by this additional material. [It’s available as a boxed set which is also known slightly mischievously as the ‘Proust 6-pack’.]

There’s also a more recent version produced by seven different translators. This has the advantage of being the most up to date. It is based on the latest version of a text with a very tangled provenance, and each translator writes a preface on the problems of translation. This version got a mixed reception when it first appeared. Some people argue that it removes a certain prissiness which had clung to the English version of Proust since Scott Moncrieff’s translation. Others have claimed that it introduces new problems and lacks a unifying voice. Perhaps the best reason for choosing it is that it’s now generally available at a cut-down price.

There’s also a more recent version produced by seven different translators. This has the advantage of being the most up to date. It is based on the latest version of a text with a very tangled provenance, and each translator writes a preface on the problems of translation. This version got a mixed reception when it first appeared. Some people argue that it removes a certain prissiness which had clung to the English version of Proust since Scott Moncrieff’s translation. Others have claimed that it introduces new problems and lacks a unifying voice. Perhaps the best reason for choosing it is that it’s now generally available at a cut-down price.

The Cambridge Companion to Proust provides essays on the major features of Marcel Proust’s great work. These investigate such essential areas as the composition of the novel, its social dimension, the language in which it is couched, its intellectual parameters, its humour, its analytical profundity and its wide appeal and influence. This is suitable for those who want to study Proust in depth. The discussion is illustrated by textual quotation (in both French and English) and close analysis. This is the only volume of its kind on Proust currently available. It contains a detailed chronology and bibliography.

The Cambridge Companion to Proust provides essays on the major features of Marcel Proust’s great work. These investigate such essential areas as the composition of the novel, its social dimension, the language in which it is couched, its intellectual parameters, its humour, its analytical profundity and its wide appeal and influence. This is suitable for those who want to study Proust in depth. The discussion is illustrated by textual quotation (in both French and English) and close analysis. This is the only volume of its kind on Proust currently available. It contains a detailed chronology and bibliography.

Marcel Proust is an excellent biography by George Painter. This study has become famous in its own right, because it combines deep insights with scholarly rigour – and it is also written in a very stylish manner. Painter sketches in the background to Parisian society, which provides a historical context for what follows. He then traces Proust’s singular life (the neurasthenia, the ‘job’ he kept for one day, the cork-lined bedroom) up to his death in 1922 – where he was still revising his masterpiece in bed, which is where he had written most of it. This is regarded as a classic of modern biography, and in 1965 it was awarded the Duff Cooper Memorial Prize.

Marcel Proust is an excellent biography by George Painter. This study has become famous in its own right, because it combines deep insights with scholarly rigour – and it is also written in a very stylish manner. Painter sketches in the background to Parisian society, which provides a historical context for what follows. He then traces Proust’s singular life (the neurasthenia, the ‘job’ he kept for one day, the cork-lined bedroom) up to his death in 1922 – where he was still revising his masterpiece in bed, which is where he had written most of it. This is regarded as a classic of modern biography, and in 1965 it was awarded the Duff Cooper Memorial Prize.

AND … now for something completely different

Other works by Marcel Proust

![]() Jean Santeuil

Jean Santeuil

This was Proust’s ‘dry run’ for his major work. It’s an unfinished (though quite long) fragment of a novel about the life of a young Parisian man which tells the story of boyhood summers of strawberries and cream cheese, of garlands of pink blossom under branches of white may, of love and its lies, of political scandal and of his deep feeling for his parents.

![]() The Pleasures and the Days

The Pleasures and the Days

Set amid fin-de-siecle Parisian salon society, these sketches and short stories depict the lives, loves, manners and motivations of a host of characters, all viewed with a characteristically knowing eye. By turns cuttingly satirical and bitterly moving, Proust’s portrayals are layered with imagery and feeling, whether they be of the aspiring Bouvard and Pecuchet, the deluded Madame de Breyves, or Baldassare Silvande, saturated with regret, memory and final understanding at the end of his life.

![]() Contre Saint Beuve

Contre Saint Beuve

This series of essays has as its centrepiece Proust’s literary manifesto. In it he argues for an essentially modernist position – that works of art should be considered autonomously, rather than objects which we use as a means of exploring the author’s biography.

![]() The Complete Short Stories of Marcel Proust

The Complete Short Stories of Marcel Proust

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on Marcel Proust

Twentieth century literature

More on biography

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

1882. James Joyce was born in Dublin, the eldest of ten children. His father was a rather improvident tax collector. The family became progressively impoverished.

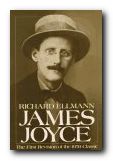

1882. James Joyce was born in Dublin, the eldest of ten children. His father was a rather improvident tax collector. The family became progressively impoverished. James Joyce

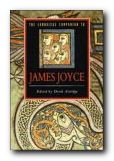

James Joyce The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book, London: Routledge, 1996.

Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book, London: Routledge, 1996. The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism. Dubliners is his first major work – a ground-breaking collection of short stories in which he strips away all the decorations and flourishes of late Victorian prose style. What remains is a sparse yet lyrical exposure of small moments of revelation – which he called ‘epiphanies’. Like other modernists, such as Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, Joyce minimised the dramatic element of the short story in favour of symbolic meaning and a more static aesthetic. This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century. The collection ends with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. It caused controversy when it first appeared, and was the first of many of Joyce’s works to be banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories. New readers should start here.

Dubliners is his first major work – a ground-breaking collection of short stories in which he strips away all the decorations and flourishes of late Victorian prose style. What remains is a sparse yet lyrical exposure of small moments of revelation – which he called ‘epiphanies’. Like other modernists, such as Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, Joyce minimised the dramatic element of the short story in favour of symbolic meaning and a more static aesthetic. This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century. The collection ends with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. It caused controversy when it first appeared, and was the first of many of Joyce’s works to be banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories. New readers should start here. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return. Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day. Finnegans Wake is famous in literary circles as a great novel which almost no one has ever read. Joyce said that he spent seventeen years of his life writing Finnegans Wake and that he expected readers to spend the rest of their lives trying to understand it. It continues where Ulysses leaves off in terms of linguistic complexity. Written and rewritten many times over, Joyce eventually decided to incorporate many languages other than English into the narrative. It is a fantastic crossword-puzzle of puns, parodies, jokes and linguistic invention which make enormous intellectual demands on the reader. This, in addition to the many arcane references and a very complex narrative make Finnegans Wake a literary experiment which has never been surpassed. It is one of the great unread masterpieces of twentieth century literature.

Finnegans Wake is famous in literary circles as a great novel which almost no one has ever read. Joyce said that he spent seventeen years of his life writing Finnegans Wake and that he expected readers to spend the rest of their lives trying to understand it. It continues where Ulysses leaves off in terms of linguistic complexity. Written and rewritten many times over, Joyce eventually decided to incorporate many languages other than English into the narrative. It is a fantastic crossword-puzzle of puns, parodies, jokes and linguistic invention which make enormous intellectual demands on the reader. This, in addition to the many arcane references and a very complex narrative make Finnegans Wake a literary experiment which has never been surpassed. It is one of the great unread masterpieces of twentieth century literature.