tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

The Legacy was a short story commissioned by the American magazine Harper’s Bazaar in 1940. However, without offering any explanation, they declined to publish it, despite angry letters of complaint from Virginia Woolf to the editor.

The Legacy – critical commentary

By the late 1930s Virginia Woolf’s period of literary experimentation was coming to an end, and she returned to a more traditional manner of presentation. After the highpoint of The Waves in 1931 she produced the more conventional The Years (1937), the biography Roger Fry, and her last novel Between the Acts (1940). She also produced far less short fiction and concentrated instead on essays and polemics such as Three Guineas (1938). So it is not surprising to find her returning to earlier conventions of the short story in her composition of The Legacy.

Certainly it sits alongside some of her other short fictions from the 1920s and 1930s in being a study in egoism and complacency, but she comes back to the strategy of the ‘surprise ending’ which dates back to the nineteenth century and writers such as Guy de Maupassant.

Of course an alert first time reader might not find the ending altogether surprising. After all, why would Angela have left her effects labeled as gifts for other people unless she was preparing for her own death? BM’s death too is foretold by a brief mention in the opening of the story – but we do not know his significance at that point in the story.

What we do know from the conventions of story plotting is that someone reading another person’s intimate diaries for the first time in fifteen years is likely to be in for something of a surprise revelation or shock to the system.

The highlight of this particular story is Woolf’s well-paced depiction of emotional disintegration as Gilbert Clandon plummets from smug self-regard into the agonies of unappeasable jealousy as he discovers the truth of Angela’s secret life – culminating in his realisation that she chose to follow her lover into death.

The Legacy – study resources

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

![]() Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

![]() Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon UK

Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon UK

![]() Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon US

Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon US

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Legacy – story synopsis

Gilbert Clandon, a prominent politician, is clearing away his wife’s effects following her sudden death in a road accident. He presents Sissy Miller, his wife’s secretary, with a brooch, and offers to help her in any way he can. She makes him a similar offer, which he interprets as the sign of a secret passion she has for him.

He then begins to look through his wife’s private diaries that she has left him as her personal legacy. He basks in a glow of satisfaction on reading the flattering entries she has written about him. As he reads on it becomes apparent that the childless Angela was trying to make an independent life for herself.

First she takes up charity work in the East End; then she befriends someone referred to by the initials BM, who is obviously a lower class radical with critical views on the upper class. Gilbert instinctively disapproves of him and is shocked to learn that she had invited BM to dinner on an occasion when Gilbert himself was giving a speech at the Mansion House.

As he reads on, Gilbert becomes incensed with retrospective jealousy and feels a shattering blow to his own ego. Finally, the diary records BM pressing Angela to make a decision, coupled with some sort of threat. Desperate to know the identity of BM, Gilbert telephones Sissy Miller and demands to know who it is. Sissy reveals that it was her brother, who committed suicide – and Gilbert realises that his wife Angela has done the same thing.

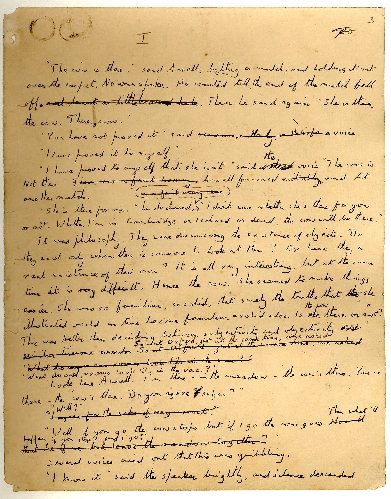

Virginia Woolf’s handwriting

“I feel certain that I am going mad again.”

Further reading

![]() Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

![]() Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

![]() Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

![]() John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

![]() Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

![]() Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

![]() Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

![]() Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

![]() Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Other works by Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

Blogging Woolf

Book reviews, Bloomsbury related issues, links, study resources, news of conferences, exhibitions, and events, regularly updated.

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of her work, fiction and non-fiction publications, photograph albumns, list of biographies, and external web links

Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Selected eTexts of her novels and stories in a variety of digital formats.

Woolf Online

An electronic edition and commentary on To the Lighthouse with notes on its composition, revisions, and printing – plus relevant extracts from the diaries, essays, and letters.

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search texts of all the major novels and essays, word by word – locate quotations, references, and individual terms

Orlando – Sally Potter’s film archive

The text and film script, production notes, casting, locations, set designs, publicity photos, video clips, costume designs, and interviews.

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury – including Gordon Square, Gower Street, Bedford Square, Tavistock Square, plus links to women’s history web sites.

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Bulletins of events, annual lectures, society publications, and extensive links to Woolf and Bloomsbury related web sites

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

Charming sound recording of radio talk given by Virginia Woolf in 1937 – a podcast accompanied by a slideshow of photographs.

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephen compiled a photograph album and wrote an epistolary memoir, known as the “Mausoleum Book,” to mourn the death of his wife, Julia, in 1895 – an archive at Smith College – Massachusetts

Virginia Woolf first editions

Hogarth Press book jacket covers of the first editions of Woolf’s novels, essays, and stories – largely designed by her sister, Vanessa Bell.

Virginia Woolf – on video

Biographical studies and documentary videos with comments on Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group and the social background of their times.

Virginia Woolf Miscellany

An archive of academic journal essays 2003—2014, featuring news items, book reviews, and full length studies.

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – short stories

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

Virginia Woolf – life and works

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Washington Square

Washington Square

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece. Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed.

Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed.

The Kingdom of This World

The Kingdom of This World The Chase

The Chase