tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

Paste first appeared in Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly in December 1899. It was then reprinted in the collection of tales The Soft Side published by Methuen in 1900.

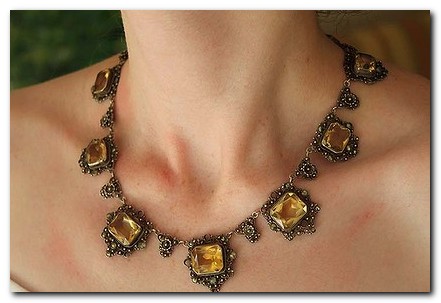

The Necklace

Paste – critical commentary

Historical background

The crux of this story is based on a social factor which might seem rather obscure in the twenty-first century. It’s the fact that actresses (and any women associated with the stage) were regarded from the Renaissance right up to the twentieth century as synonymous with loose morals and even prostitution.

It was very common for upper class males (and even royalty) to have mistresses who were singers or actresses. These women were either set up in premises or showered with gifts by their suitors – who were often described in euphemistic terms such as ‘protector’ or ‘admirer’.

It was a form of prostitution – and was tolerated because it did not threaten the established order. The procuring male bought the sexual favours of the female, and his place in society as either a bachelor or a man who had married within his own class remained unthreatened.

Why was it the stage rather than other occupations which should have given rise to this practice? Presumably because as singers or performers, the women would be more socially mobile, and would operate in a zone which was close to but not part of polite society.

The occupation of singer or actress was regarded as declasse. Arthur’s father (as a vicar) has courted social danger in marrying an actress, and the explanation for Arthur’s priggishness (and lies) is that he wishes to protect his family’s (and his own) reputation.

Literary tradition

This story is a variation on a tale made famous by Guy de Maupassant in 1884 called The Necklace (La Parure). Henry James was a personal friend of Maupassant, and wrote a critical study of his work in French Writers.

In Maupassant’s story a socially ambitious married woman borrows a diamond necklace to attend a grand public event. She loses the necklace and is forced to replace it, putting herself and husband in crippling debt. It takes them more than ten years of privation to repay the loan – at which point she discovers that the diamonds were only fakes, worth next to nothing.

The same theme was given a further twist by Somerset Maugham in his story A String of Beads (1927). In this version a young governess appears at a dinner party wearing a string of pearls which a fellow guest says are real and worth a small fortune. She says she paid fifteen shillings for them in a department store. Then two representatives from the store arrive and explain that she has been given the wrong pearls by mistake. They present her with three hundred pounds as compensation – which she lavishes on an expensive holiday in Deauville, mixing with rich men. She eventually becomes a courtesan, living in high style in Paris.

This story was itself a second variation on this theme, to which Maugham makes inter-textual reference. In Mr Know-All a young woman appears at dinner on a cruise ship wearing a set of pearls. A rather annoying guest claims he knows all about pearls and that they are worth a lot of money. The woman’s husband says she bought them for eighteen dollars. The two men have a one hundred dollar bet on who is right. But then Mr Know-All, seeing the woman’s discomfort, suddenly backs down, realising they must have been a gift from another man, presumably her lover. Next day she returns to him the one hundred dollars he gallantly forfeited to her husband.

Paste – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1898—1910 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() Paste – HTML version at Gutenberg

Paste – HTML version at Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Paste – plot summary

Arthur Prime’s father and stepmother die within two weeks of each other. Mr Prime senior was a vicar, and his second wife was a former actress. Arthur’s cousin Charlotte is presented with a box of her old theatrical costume jewellery as a memento of her aunt. Arthur and Charlotte wonder if some of the items might be real rather than fake, and if they turn out to be real, were possibly a present from an admirer. But Arthur priggishly denies this suggestion, claiming that his stepmother’s reputation was above reproach.

When a party is being organised by Charlotte’s employer, her associate Mrs Guy borrows the jewellery for a tableau vivant and reveals that a string of pearls are real, not fake. Charlotte thinks she is obliged to return them, but realises that to do so would reveal to Arthur their origin as a ‘gift’ from an actress’s ‘admirer’.

Mrs Guy wears the pearls to dinner and they are much admired. She even offers to buy them. Charlotte still thinks she ought to return them, but starts wearing them in private. Some months later she confronts Arthur with the truth about the pearls. He refuses to believe that they are real, and says he will seek a professional opinion.

He later writes to Charlotte telling her that the pearls are fake, but Charlotte meets Mrs Guy wearing them. She has bought them in Bond Street from a jeweller. Charlotte knows that Arthur has lied, but she also wonders if Mrs Guy has bought them directly from Arthur, since she knew his address.

Principal characters

| Arthur Prime | a prissy young man |

| Charlotte Prime | his cousin, a governess |

| Mrs Guy | a social events organiser |

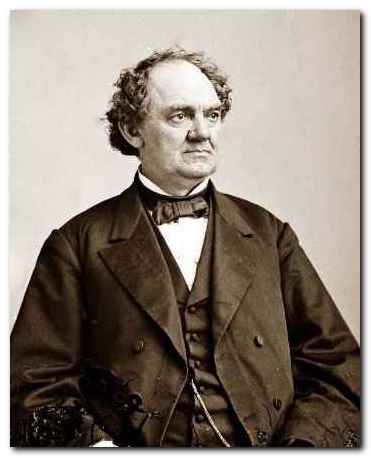

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict and authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict and authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

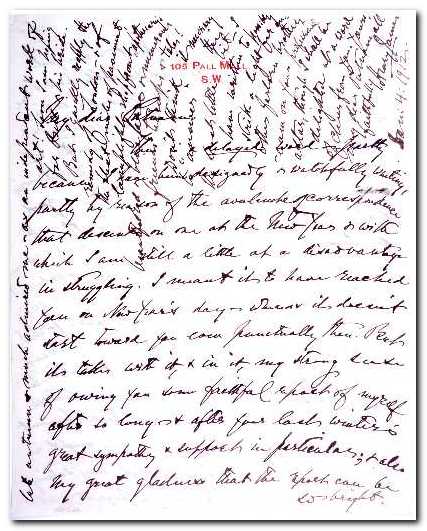

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.