tutorial, commentary, study resources, and full text

In the Orchard was written in 1923 – between the composition of Jacob’s Room (1922) and Mrs Dalloway (1925). It was first published in the magazine The Criterion in April 1923 – edited by he friend and fellow Bloomsbury Group member T.S. Eliot.

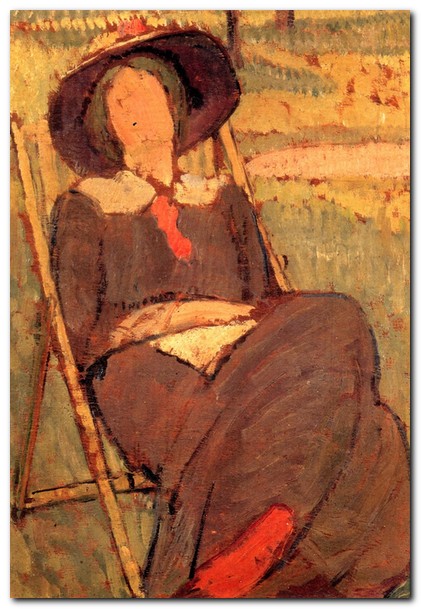

Virginia Woolf – by Vanessa Bell

In the Orchard – critical commentary

Structure

The story is in three parts, each one starting with the same words ‘Miranda slept in the orchard’. The external events alluded to remain the same in each section, but the images and leitmotifs, and to some extent the perspective changes in each section – which are only signaled by extra space between paragraphs.

Content

Part One – In this section the dominant motifs are sounds – the cries of the children learning multiplication tables; the church organ where Hymns Ancient and Modern are being played; the church bells when women are being churched; and the squeak of the weather vane on the church tower as the wind changes direction. These elements are also are also discussed on a vertical axis in relationship to each other.

Part Two – In this section the content is largely Miranda’s thoughts about herself in relationship to the world – on a cliff or in relationship to the sea. She perceives these elements as connected. But they are interspersed with some of the same elements from Part One – the children in school, the cry of the drunken man, the Hymns Ancient and Modern.

Part Three – In this section there is an almost geometric account of the orchard space itself, with the apple-trees growing out of the ground, birds flitting across between its walls, and an emphasis on the relationship between the earth and the air.

The elements of this piece are distinctly rural – an orchard, a village church, apple trees, the herding of cattle – though it has to be said that Virginia Woolf went on to produce the same effects in the urban landscape of Mrs Dalloway.

Biography

It should be noted that at a biographical level of commentary, all of the elements of this story would be available when sitting in the garden at Monk’s House, where Virginia Woolf was living at the time. The garden of the House is adjacent to both the church and the local school, and the whole area is surrounded by the working environment of farming and livestock production.

Style and experimentation

Virginia Woolf was very close to a number of painters who were members of the Bloomsbury Group – primarily her sister Vanessa Bell and Bell’s lover Duncan Grant, but also the painter and art theorist Roger Fry whose biography she wrote.

They were all interested in escaping the demand for descriptive detail in painting, and rendering only what Roger Fry called ‘essential form’. That is, they wanted to render only the basic visual elements of a composition. It was a step towards what we now call ‘abstraction’. In the Orchard is fairly clearly an experiment in doing something similar with prose, rather than paint.

In Woolf’s case she removes the normal substance of prose fiction – the element of a human being involved in some form of drama – and substitutes a combination of visual imagery, of philosophic reflections, and grammatical constructs which tie these elements together. This experimental story is an exercise in what might be called literary cubism – the same scene is viewed from different perspectives. It also has elements of what many people would probably wish to call ‘impressionism’ – the fleeting evocation of sounds, light, colours, and wind to create a sense of the flux of everyday existence.

When the breeze blew, her purple dress rippled like a flower attached to a stalk; the grasses nodded; and the white butterfly came blowing this way and tat just above her face.

The changing subject – the flitting from visual image to aural echo, and on to geographic context – from light and shade to chimes, and on to clouds or the waves of the sea – is a literary device she used in major works from Jacob’s Room (1922) to Between the Acts (1941). She made it her own – like a signature style.

The only other prominent modernist writer who used it (but at a far slower tempo) was Marcel Proust, and interestingly enough he was doing it at the same time in the volumes of A la recherche du temps perdus he published between 1913 and 1927 and which Virginia Woolf read with great enthusiasm.

Woolf also moves fluently between narrative modes – from third person omniscient to (briefly) first person, and then back again

and then she smiled and let her body sink all its weight in to the enormous earth which rises, she thought, to carry me on its back as if I were a leaf, or a queen (here the children said the multiplication table) …

The human element of fiction

There does appear to be a human subject in the narrative – Miranda in the orchard. But she is asleep (or may not be) and she has no more importance than the other elements of the narrative except as an object to which the focus of attention keeps returning.

It is a successful exercise, a sketch, a literary experiment to place alongside Monday or Tuesday or Kew Gardens. But it does emphasise the fact that the essence of fictional narratives (as distinct from word-painting and lyrical descriptions) is that we expect to find some sort of human drama enacted, no matter how simple or understated.

The nearest we get to this here is Miranda (provided that she is not asleep) enjoys a sort of epiphany when linking together the elements of her sense experiences and feeling a one-ness with the world around her. But it has to be said that the epiphany is more of the author’s making than enacted properly in Miranda’s consciousness. Woolf as author is making these connections between the earth, the air, the wind, the orchard, and even the cabbages. She does not persuade us that Miranda is conscious of them.

In the Orchard – study resources

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

![]() Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

![]() Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon UK

Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon UK

![]() Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon US

Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon US

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle edition

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

![]() Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

Virginia Woolf – Authors in Context – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf – Amazon UK

In the Orchard – the text

Miranda slept in the orchard, lying in a long chair beneath the apple tree. Her book had fallen into the grass, and her finger still seemed to point at the sentence ‘Ce pays est vraiment un des coins du monde ou le rire des filles eclate le mieux. …’ as if she had fallen asleep just there. The opals on her finger flushed green, flushed rosy, and again flushed orange as the sun, oozing through the apple-trees, filled them. Then, when the breeze blew, her purple dress rippled like a flower attached to a stalk; the grasses nodded; and the white butterfly came blowing this way and that just above her face.

Four feet in the air above her head the apples hung. Suddenly there was a shrill clamour as if they were gongs of cracked brass beaten violently, irregularly, and brutally. It was only the school-children saying the multiplication table in unison, stopped by the teacher, scolded, and beginning to say the multiplication table over again. But this clamour passed four feet above Miranda’s head, went through the apple boughs, and, striking against the cowman’s little boy who was picking blackberries in the hedge when he should have been at school, made him tear his thumb on the thorns.

Next there was a solitary cry — sad, human, brutal. Old Parsley was, indeed, blind drunk.

Then the very topmost leaves of the apple-tree, flat like little fish against the blue, thirty feet above the earth, chimed with a pensive and lugubrious note. It was the organ in the church playing one of Hymns Ancient and Modern. The sound floated out and was cut into atoms by a flock of field-fares flying at an enormous speed — somewhere or other. Miranda lay asleep thirty feet beneath.

Then above the apple-tree and the pear-tree two hundred feet above Miranda lying asleep in the orchard bells thudded, intermittent, sullen, didactic, for six poor women of the parish were being churched and the Rector was returning thanks to heaven.

And above that with a sharp squeak the golden feather of the church tower turned from south to east. The wind changed. Above everything else it droned, above the woods, the meadows, the hills, miles above Miranda lying in the orchard asleep. It swept on, eyeless, brainless, meeting nothing that could stand against it, until, wheeling the other way, it turned south again. Miles below, in a space as big as the eye of a needle, Miranda stood upright and cried ‘Oh I shall be late for tea!’.

Miranda slept in the orchard — or perhaps she was not asleep, for her lips moved slightly, as if she were saying ‘Ce pays est vraiment un des coins du monde … ou le rire des filles … eclate … eclate … eclate’, and then she smiled and let her body sink all its weight in to the enormous earth which rises, she thought, to carry me on its back as if I were a leaf, or a queen (here the children said the multiplication table), or, Miranda went on, I might be lying on the top of a cliff with the gulls screaming above me. The higher they fly, she continued, as the teacher scolded the children and rapped Jimmy over the knuckles till they bled, the deeper they look into the sea — into the sea she repeated, and her fingers relaxed and her lips closed gently as if she were floating on the sea, and then, when the shout of the drunken man sounded overhead, she drew breath with an extraordinary ecstasy, for she thought she had heard life itself crying out from a rough tongue in a scarlet mouth, from the wind, from the bells, from the curved green leaves of the cabbages.

Naturally she was being married when the organ played the tune from Hymns Ancient and Modern, and, when the bells rang after the six poor women had been churched, the sullen intermittent thud made her think that the very earth shook with the hoofs of the horse that was galloping towards her (‘Ah, I have only to wait!’ she sighed), and it seemed to her that everything had already begun moving, crying, riding, flying around her, across her, towards her in a pattern.

Mary is chopping the wood, she thought; Pearman is herding the cows; the carts are coming up from the meadows; the rider — and she traced out the lines that the men, the carts, the birds, and the rider made over the countryside until they all seemed driven out, round, and across by the beat of her own heart.

Miles up in the air the wind changed; the golden feather of the church tower squeaked; and Miranda jumped up and cried ‘Oh I shall be late for tea!’

Miranda slept in the orchard, or was she asleep or was she not asleep? Her purple dress stretched between the two apple-trees. There were twenty-four apple-trees/in the orchard, some slanting slightly, others growing straight with a rush up the trunk which spread wide into branches and formed into red or yellow drops. Each apple-tree had sufficient space. The sky exactly fitted the leaves. When the breeze blew, the line of the boughs against the wall slanted slightly and then returned. A wagtail flew diagonally from one corner to another. Cautiously hopping, a thrush advanced towards a fallen apple; from the other wall a sparrow fluttered just above the grass. The uprush of the trees was tied down by these movements; the whole was compacted by the orchard walls. For miles beneath the earth was clamped together; rippled on the surface with wavering air; and across the corner of the orchard the blue-green was slit by a purple streak. The wind changing, one bunch of apples was tossed so high that it blotted out two cows in the meadow (‘Oh, I shall be late for tea!’ cried Miranda), and the apples hung straight across the wall again.

Writing – I

Mont Blanc pen – the Virginia Woolf special edition

Further reading

![]() Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

![]() Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

![]() Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

![]() John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

![]() Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

![]() Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

![]() Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

![]() Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

![]() Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Other works by Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

To the Lighthouse (1927) is the second of the twin jewels in the crown of her late experimental phase. It is concerned with the passage of time, the nature of human consciousness, and the process of artistic creativity. Woolf substitutes symbolism and poetic prose for any notion of plot, and the novel is composed as a tryptich of three almost static scenes – during the second of which the principal character Mrs Ramsay dies – literally within a parenthesis. The writing is lyrical and philosophical at the same time. Many critics see this as her greatest achievement, and Woolf herself realised that with this book she was taking the novel form into hitherto unknown territory.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

Blogging Woolf

Book reviews, Bloomsbury related issues, links, study resources, news of conferences, exhibitions, and events, regularly updated.

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of her work, fiction and non-fiction publications, photograph albumns, list of biographies, and external web links

Virginia Woolf at Gutenberg

Selected eTexts of her novels and stories in a variety of digital formats.

Woolf Online

An electronic edition and commentary on To the Lighthouse with notes on its composition, revisions, and printing – plus relevant extracts from the diaries, essays, and letters.

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search texts of all the major novels and essays, word by word – locate quotations, references, and individual terms

Orlando – Sally Potter’s film archive

The text and film script, production notes, casting, locations, set designs, publicity photos, video clips, costume designs, and interviews.

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury – including Gordon Square, Gower Street, Bedford Square, Tavistock Square, plus links to women’s history web sites.

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Bulletins of events, annual lectures, society publications, and extensive links to Woolf and Bloomsbury related web sites

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

Charming sound recording of radio talk given by Virginia Woolf in 1937 – a podcast accompanied by a slideshow of photographs.

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephen compiled a photograph album and wrote an epistolary memoir, known as the “Mausoleum Book,” to mourn the death of his wife, Julia, in 1895 – an archive at Smith College – Massachusetts

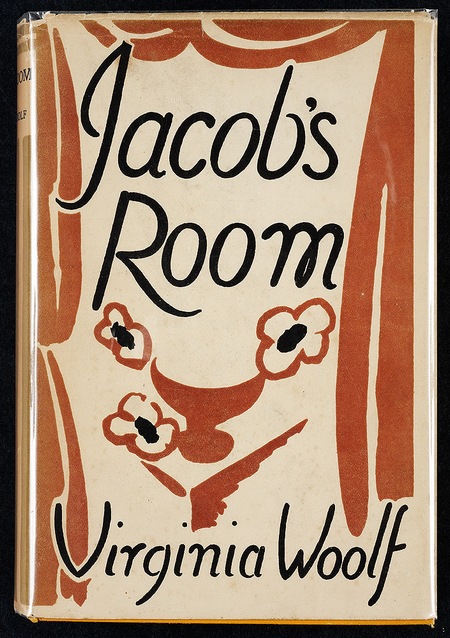

Virginia Woolf first editions

Hogarth Press book jacket covers of the first editions of Woolf’s novels, essays, and stories – largely designed by her sister, Vanessa Bell.

Virginia Woolf – on video

Biographical studies and documentary videos with comments on Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group and the social background of their times.

Virginia Woolf Miscellany

An archive of academic journal essays 2003—2014, featuring news items, book reviews, and full length studies.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – short stories

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

Virginia Woolf – life and works

1882. James Joyce was born in Dublin, the eldest of ten children. His father was a rather improvident tax collector. The family became progressively impoverished.

1882. James Joyce was born in Dublin, the eldest of ten children. His father was a rather improvident tax collector. The family became progressively impoverished. James Joyce

James Joyce The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce

Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book, London: Routledge, 1996.

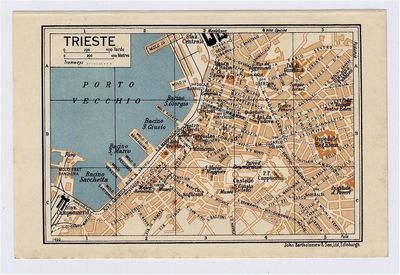

Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book, London: Routledge, 1996. The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism. Dubliners is his first major work – a ground-breaking collection of short stories in which he strips away all the decorations and flourishes of late Victorian prose style. What remains is a sparse yet lyrical exposure of small moments of revelation – which he called ‘epiphanies’. Like other modernists, such as Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, Joyce minimised the dramatic element of the short story in favour of symbolic meaning and a more static aesthetic. This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century. The collection ends with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. It caused controversy when it first appeared, and was the first of many of Joyce’s works to be banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories. New readers should start here.

Dubliners is his first major work – a ground-breaking collection of short stories in which he strips away all the decorations and flourishes of late Victorian prose style. What remains is a sparse yet lyrical exposure of small moments of revelation – which he called ‘epiphanies’. Like other modernists, such as Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, Joyce minimised the dramatic element of the short story in favour of symbolic meaning and a more static aesthetic. This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century. The collection ends with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. It caused controversy when it first appeared, and was the first of many of Joyce’s works to be banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories. New readers should start here. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return. Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day. Finnegans Wake is famous in literary circles as a great novel which almost no one has ever read. Joyce said that he spent seventeen years of his life writing Finnegans Wake and that he expected readers to spend the rest of their lives trying to understand it. It continues where Ulysses leaves off in terms of linguistic complexity. Written and rewritten many times over, Joyce eventually decided to incorporate many languages other than English into the narrative. It is a fantastic crossword-puzzle of puns, parodies, jokes and linguistic invention which make enormous intellectual demands on the reader. This, in addition to the many arcane references and a very complex narrative make Finnegans Wake a literary experiment which has never been surpassed. It is one of the great unread masterpieces of twentieth century literature.

Finnegans Wake is famous in literary circles as a great novel which almost no one has ever read. Joyce said that he spent seventeen years of his life writing Finnegans Wake and that he expected readers to spend the rest of their lives trying to understand it. It continues where Ulysses leaves off in terms of linguistic complexity. Written and rewritten many times over, Joyce eventually decided to incorporate many languages other than English into the narrative. It is a fantastic crossword-puzzle of puns, parodies, jokes and linguistic invention which make enormous intellectual demands on the reader. This, in addition to the many arcane references and a very complex narrative make Finnegans Wake a literary experiment which has never been surpassed. It is one of the great unread masterpieces of twentieth century literature.

David Cecil, A Portrait of Jane Austen, London: Constable, 1978.

David Cecil, A Portrait of Jane Austen, London: Constable, 1978. Jane Austen: a Life is a biography which traces Jane Austen’s progress through a difficult childhood, an unhappy love affair, her experiences as a poor relation and her decision to reject a marriage that would solve all her problems – except that of continuing as a writer. Both the woman and the novels are radically reassessed in this biography. Her life was superficially uneventful, but Claire Tomalin brings out the flesh and blood woman who lies behind the cool, ironic prose.

Jane Austen: a Life is a biography which traces Jane Austen’s progress through a difficult childhood, an unhappy love affair, her experiences as a poor relation and her decision to reject a marriage that would solve all her problems – except that of continuing as a writer. Both the woman and the novels are radically reassessed in this biography. Her life was superficially uneventful, but Claire Tomalin brings out the flesh and blood woman who lies behind the cool, ironic prose. The Complete Critical Guide to Jane Austen is a good introduction to Austen criticism and commentary. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from Walter Scott to critics of the present day. It also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist journals. It also has an interesting chapter discussing Austen on the screen. These guides are very popular.

The Complete Critical Guide to Jane Austen is a good introduction to Austen criticism and commentary. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from Walter Scott to critics of the present day. It also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist journals. It also has an interesting chapter discussing Austen on the screen. These guides are very popular.