tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

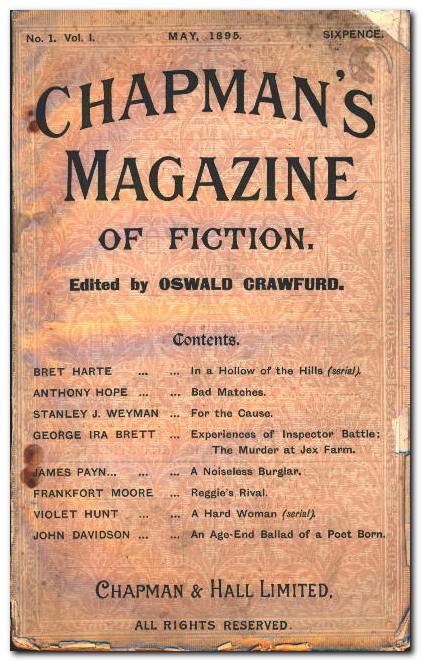

The Friends of the Friends (1896) is one of the many variations of ‘a ghost story’ that James wrote in his late period. It was originally entitled The Way it Came for its first appearance in the May issue of Chapman’s Magazine of Fiction then renamed when published in the New York Edition of James’s novels and tales which appeared in 1907-1909. Neither title seems to really summarise or capture the story in a satisfactory manner.

The Friends of the Friends – critical commentary

The ghostly reading

Those with a penchant for supernatural interpretations have sufficient evidence here to provide a coherent reading of the tale. This rests on the notion that some people have the capacity to conjure up an apparition of a person who is in fact dying in a different location. It happens to the man in the story, who was ‘visited’ by his mother in Oxford around the same time that she is dying in Wales.

If we take that as a credible possibility, then the idea that he ‘sees’ his fellow clairvoyant late at night when she appears in his rooms is merely another example of the same phenomenon. After all, she appears, then disappears. They do not speak to each other.

The female inner-narrator guesses – it would seem correctly – that he has been deeply touched by the experience, and bases her subsequent rejection of him on this curiously supernatural infidelity, especially as he subsequently admits to its continuing.

But this interpretation rests on believing the inner-narrator’s interpretation of events. She believes that the woman was dead at that time. But the man does not. He claims it was a visit from the woman herself, fully alive. He is even able to describer her appearance (the three feathers in her hat).

It’s also possible to see the supernatural events from another perspective – that of the ghosts’ point of view. The female inner-narrator sees the man’s mother and her woman friend as sharing a capacity to make appearances before the man: “a strange gift shared by her with his mother and on her side likewise hereditary”. This interpretation puts the supernatural capacity onto the dying figure, rather than the person to whom they appear.

The unreliable narrator

Interpretation of the story may come down to which account of events seems more plausible – that of the man or the female inner-narrator. It is quite feasible that the woman called to see him whilst she was still alive – though it seems rather unlikely that two people would meet under such circumstances without speaking to each other.

On the other hand, if we accept that the two ‘visitations’ by the dying parents are credible, then the inner-narrator’s claim that the man had seen and communed seriously with the woman’s ghost at the same time as she was dying has the force of logic to it. If he can see one ghost, why not another? Or as the inner-narrator sees it, her woman friend shares a hereditary capacity for ghostliness with the man’s mother.

But another element which should be taken into account is that the inner-narrator can be seen as one of James’s many emotionally unstable and possibly unreliable narrators who he created around this time. She can certainly be seen as a precursor of the governess in The Turn of the Screw. She is predisposed to jealousy even before her two friends meet each other; she manipulates and deceives both of them; she accuses her fiancé of a very peculiar form of infidelity, and of course she does not name either of them or herself in her written account of events.

The narrative frame

The one-sided frame of the narrative is cast in the form of a letter or memo, written by the outer narrator to a publisher, who has asked him to look through the papers of a woman who has died. This is another example of a James tale which begins with the death of its protagonist. The story is in fact a retrospective, and we tend to forget whilst reading that the principal character no longer exists in the fictional time frame.

In fact the term ‘framed narrative’ is slightly misleading in such cases. In its original sense it was used to describe stories which were given some sort of introduction and conclusion. The story itself was therefore a fiction within a fiction.

For example, Joseph Conrad’s famous novella Heart of Darkness begins and ends with a group of sailors talking on board a ship, waiting for the tide to turn. One of them, Marlow, recounts his experiences which constitute the main events of story. But the introductory passages set the scene, and the conclusion returns to the same point, on board the ship, thereby completing the frame. It is worth noting that Conrad, like James, uses an un-named outer-narrator to introduce Marlow as the inner-narrator.

One remarkable feature of this story is that none of the characters in it is given a name. It’s true that there are only three principal characters – the inner narrator, plus her woman and man friend, but as the outer-narrator comments, they are given ‘neither name nor initials’.

The Friend of the Friends – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1892—1898 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1892—1898 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1892—1898 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1892—1898 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Friends of the Friends – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

The Friends of the Friends – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Friends of the Friends – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

The Friends of the Friends – Oxford World Classics edition – Amazon US

![]() The Friends of the Friends – Vintage Classics edition

The Friends of the Friends – Vintage Classics edition

![]() The Ghost Stories of Henry James – Wordsworth edition

The Ghost Stories of Henry James – Wordsworth edition

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() The Friends of the Friends – read the book on line

The Friends of the Friends – read the book on line

![]() The Friends of the Friends – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

The Friends of the Friends – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

The Friends of the Friends – plot summary

A woman has two friends (a man and a woman) who both have the same supernatural experience of witnessing the appearance of a parent who at the very same moment is dying in another location. The woman thinks that they would like to meet each other so as to compare their experiences. However, both of them prevaricate over making the necessary arrangements.

The initial woman eventually becomes engaged to the man, and sets up a rendezvous between her two friends. But when she learns that the other woman’s husband has suddenly died she has a jealous fear that their common experience might draw them close to each other. She sends a message delaying the meeting with her fiancé until dinner later the same day.

The second woman visits the first in the afternoon as planned, and predicts that she will never meet the man, even at the forthcoming wedding. When she has gone, the man visits for dinner and the woman guiltily confesses her deception, then promises to do the same for her friend.

Next day she goes to Richmond, only to discover that her friend is dead. She goes back to report this to the man, who reveals that the woman visited him after he got back from dinner the night before. He claims that they never spoke, but he was very struck by her presence.

He cannot produce any concrete evidence that this visit took place, so the woman tries to convince him that he has seen a ghost – as he did when he witnessed the apparition of his mother. He tries to reassure her, but she feels jealous of the affect her friend has had on him.

The other woman is buried, but as the date of the marriage approaches the first woman feels that the friend has come between them, and eventually accuses her fiancé of ‘seeing’ her privately every evening, something he is unable to deny. So she calls off the marriage and they separate. Six years later he dies, and because his demise is sudden and inexplicable, she feels that he has gone in a ‘response to an irresistible call’.

Principal characters

| I | an un-named outer narrator who presents the written story |

| I | an un-named inner female narrator who has written the story |

| — | her pretty un-named woman friend, whose husband dies |

| — | her un-named male friend, to whom she becomes engaged |

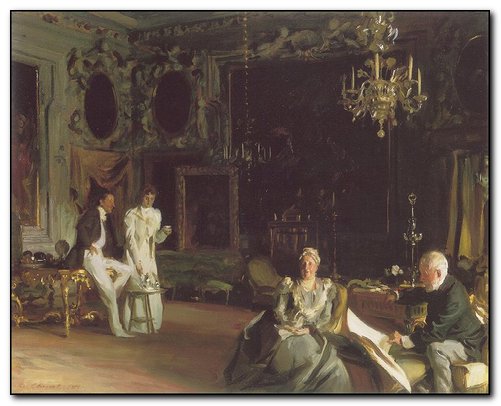

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ghost stories by Henry James

![]() The Romance of Certain Old Clothes (1868)

The Romance of Certain Old Clothes (1868)

![]() The Ghostly Rental (1876)

The Ghostly Rental (1876)

![]() Sir Edmund Orme (1891)

Sir Edmund Orme (1891)

![]() The Private Life (1892)

The Private Life (1892)

![]() Owen Wingrave (1892)

Owen Wingrave (1892)

![]() The Friends of the Friends (1896)

The Friends of the Friends (1896)

![]() The Turn of the Screw (1898)

The Turn of the Screw (1898)

![]() The Real Right Thing (1899)

The Real Right Thing (1899)

![]() The Third Person (1900)

The Third Person (1900)

![]() The Jolly Corner (1908)

The Jolly Corner (1908)

Other works by Henry James

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

© Roy Johnson 2012

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton