tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

The Marriages was first published in the Atlantic Monthly in August 1891. It was collected in Volume 8 of The Complete Tales of Henry James (Rupert Hart-Davis) 1963.

The Marriages – critical commentary

The main theme

The story is fuelled by Adela’s jealousy and her Elektra-like ambition to drive away erotic competition for her father. She is motivated by naked animosity towards Mrs Churchley from the very beginning of the story.

This presents readers with a problem, because almost all the information we have concerning Mrs Churchley is mediated via Adela, whose point of view controls the narrative.

She was as undomestic as a shop-front and as out of tune as a parrot. She would make them live in the streets, or bring the streets into their lives—it was the same thing. She had evidently never read a book, and she used intonations that Adela had never heard, as if she had been an Australian or an American.

This view of Mrs Churchley merely reflects Adela’s feelings about her prospective step-mother. It is not an objective portrait. Indeed, no objective portrait is presented.

Colonel Chant loses a chance of re-marriage through his daughter’s duplicity; Godfrey gains a wife he doesn’t really need; the wife loses her husband when she is bought off by Colonel Chart. It’s a story in which almost nobody gets what they wish for.

The Marriages – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1884—1891 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Tales (Vol 8) – Paperback edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Tales (Vol 8) – Paperback edition – Amazon UK

![]() Selected Tales – Penguin Classics edition – Amazon UK

Selected Tales – Penguin Classics edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Marriages – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

The Marriages – eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

The Marriages – plot summary

Part I. Adela Chart has recently lost her mother, to whom she was and remains devoted. She now feels jealously annoyed at her father’s attentions to Mrs Churchley, a rich but flamboyant woman. Adela tries to enlist the support of her brother Godfrey to disapprove of their father’s liaison, but Godfrey is preoccupied with exam preparations and does not share her anxieties.

Part II. A marriage date is set. Adela visits Mrs Churchley, following which the wedding is postponed. Colonel Chart sends his daughters to the family house in the country. Godfrey passes his exams, but before leaving for a posting in Madrid he visits Adela and demands to know what she has said to Mrs Churchley.

Part III. Adela reveals that she invented a story that her father mistreated their mother whilst she was alive. Godfrey is outraged and accuses Adela of spoiling his chances, causing Adela to fear that he has some guilty secret to hide.

Part IV. A tarty young woman arrives who reveals that she is married to Godfrey. Arrangements are made by Colonel Chart to pay off the woman with £600 per year so as not to spoil Godfrey’s chances in the diplomatic corps. Adela eventually goes to see Mrs Churchley to confess her lie. But Mrs Churchley makes it clear that she never believed her in the first place, and called off the marriage because she didn’t want her as a daughter-in-law.

Principal characters

| Adela Chart | a young woman whose mother has recently died |

| Colonel Chart | her father, a widower |

| Godfrey Chart | her younger brother who is cramming for civil service exams |

| Leonard Chart | another brother, who is in the army in India |

| Beatrice and Muriel | her younger sisters |

| Miss Flynn | their governess |

| Mrs Churchley | a wealthy and larger-than-life woman |

| Seymour Street | the Chant family home in London |

| Overland | the Chant family home in the country |

Henry James’s study

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

Daisy Miller (1879) is a key story from James’s early phase in which a spirited young American woman travels to Europe with her wealthy but commonplace mother. Daisy’s innocence and her audacity challenge social conventions, and she seems to be compromising her reputation by her independent behaviour. But when she later dies in Rome the reader is invited to see the outcome as a powerful sense of a great lost potential. This novella is a great study in understatement and symbolic power.

Daisy Miller (1879) is a key story from James’s early phase in which a spirited young American woman travels to Europe with her wealthy but commonplace mother. Daisy’s innocence and her audacity challenge social conventions, and she seems to be compromising her reputation by her independent behaviour. But when she later dies in Rome the reader is invited to see the outcome as a powerful sense of a great lost potential. This novella is a great study in understatement and symbolic power.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

![]() Henry James at Mantex

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

![]() The Complete Works

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

![]() The Ladder – a Henry James website

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

![]() A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

![]() The Henry James Resource Center

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

![]() Online Books Page

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

![]() Henry James at Project Gutenberg

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

![]() The Complete Letters

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

![]() The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

![]() Henry James – The Complete Tales

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

![]() Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2012

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

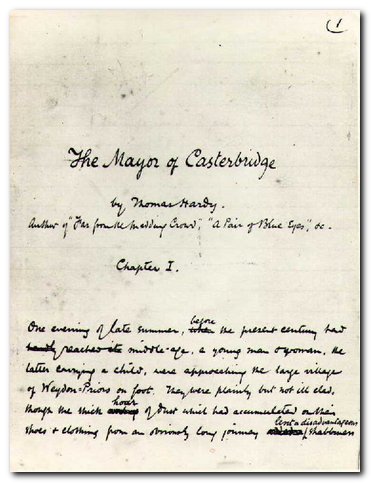

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles Jude the Obscure

Jude the Obscure Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth