A guide through James Joyce’s Ulysses

Anyone who has ever tried to read James Joyce’s Ulysses will know that it is a long, complex novel that is quite difficult to understand – especially on first acquaintance. But it is worth the effort, because it is also a twentieth-century masterpiece. The New Bloomsday Book by Joyce scholar Harry Blamires is designed to help you if you feel in need of support. It tells you what is going on from first page to last.

Ulysses, as its title suggests, is based loosely on Homer’s Odyssey, and Joyce made the events of his narrative, set on a single day in June 1914, parallel the events of the epic poem. Instead of Ulysses making his way home after fighting in the Trojan wars, Joyce’s hero Leopold Bloom, an advertising salesman, after a day of wandering around Dublin, makes his way home to his wife Molly. But the subtelties and echoes are not always easy to pick up – so Blamires guides you through the story, explaining what is going on, and pointing out the Homeric parallels.

Ulysses, as its title suggests, is based loosely on Homer’s Odyssey, and Joyce made the events of his narrative, set on a single day in June 1914, parallel the events of the epic poem. Instead of Ulysses making his way home after fighting in the Trojan wars, Joyce’s hero Leopold Bloom, an advertising salesman, after a day of wandering around Dublin, makes his way home to his wife Molly. But the subtelties and echoes are not always easy to pick up – so Blamires guides you through the story, explaining what is going on, and pointing out the Homeric parallels.

And he points out much more besides. Joyce’s novel is constructed from countless numbers of small cross references, echoes, allusions, and cultural leitmotivs. This has become a standard work of Joyce scholarship.

The ‘new’ in the title of this third edition refers to the fact that it now contains page numbering and references to the three most commonly used editions of the novel – the Oxford University Press ‘World Classics’ (1993), the Penguin ‘Twentieth-Century Classics’ (1992), and the controversial Gabler ‘Corrected Text’ (1986) editions.

It’s certainly a complete explanation, a summary of what ‘happens’ in the novel – but of course it cannot paraphrase the poetry and the glamour of the prose, whose style changes in almost every chapter – and in one memorable episode (Oxen of the Sun) within the chapter itself. As Blamires explains in his introduction to the novel’s opening chapter:

Joyce’s symbolism cannot be explained mechanically in terms of one-for-one parallels, for his correspondences are neither exclusive nor continuously persistent. Nevertheless certain correspondences recur throughout Ulysses, establishing themselves firmly. Thus Leopold Bloom corresponds to Ulysses in the Homeric Parallel, and Stephen Dedalus corresponds to Telemachus, Ulysses’s son. At the beginning of Homer’s Odyssey Telemachus finds himself virtually dispossessed by his mother’s suitors in his father’s own house, and he sets out in search of the lost Ulysses. In Joyce’s first episode Stephen Dedalus feels that he is pushed out by his supposed friends from his temporary residence, and leaves it intending not to return. The residence in question is the Martello tower on the beach at Sandycove, for which Stephen pays the rent.. Buck Mulligan, a medical student, shares it with him, and they have a resident visitor, Haines, an Englishman from Oxford.

Blamires explains all the allusions, symbols, and Homeric parallels as he goes along, whilst offering a paraphrase of the story. This will help readers to understand a dense and complex novel which might otherwise take several readings to unravel.

© Roy Johnson 2000

Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book, Abingdon: Routledge, 1996, pp.253, ISBN 0415138582

More on James Joyce

Twentieth century literature

More on study skills

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912) is a classic novella – half way between a long story and a short novel. It’s a wonderfully condensed tale of the relationship between art and life, love and death. Venice provides the background for the story of a famous German writer who departs from his usual routines, falls in love with a young boy, and gets caught up in a subtle downward spiral of indulgence. The novella is constructed on a framework of references to Greek mythology, and the unity of themes, form, and motifs are superbly realised – even though Mann wrote this when he was quite young. Later in life, Mann was to declare – ‘Nothing in Death in Venice was invented’. The story was turned into a superb film by Luchino Visconti and an opera by Benjamin Britten.

Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912) is a classic novella – half way between a long story and a short novel. It’s a wonderfully condensed tale of the relationship between art and life, love and death. Venice provides the background for the story of a famous German writer who departs from his usual routines, falls in love with a young boy, and gets caught up in a subtle downward spiral of indulgence. The novella is constructed on a framework of references to Greek mythology, and the unity of themes, form, and motifs are superbly realised – even though Mann wrote this when he was quite young. Later in life, Mann was to declare – ‘Nothing in Death in Venice was invented’. The story was turned into a superb film by Luchino Visconti and an opera by Benjamin Britten. Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd (1856) deals with a tragic incident at sea, and is based on a true occurence. It is a nautical recasting of the Fall, a parable of good and evil, a meditation on justice and political governance, and a searching portrait of three men caught in a deadly triangle. Billy is the handsome innocent, Claggart his cruel tormentor, and Captain Vere the man who must judge in the conflict between them. The narrative is variously interpreted in Biblical terms, or in terms of representations of male homosexual desire and the mechanisms of prohibition against this desire. His other great novellas Benito Cereno, The Encantadas and Bartelby the Scrivener (all in this collection) show Melville as a master of irony, point-of-view, and tone. These fables ripple out in nearly endless circles of meaning and ambiguities.

Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd (1856) deals with a tragic incident at sea, and is based on a true occurence. It is a nautical recasting of the Fall, a parable of good and evil, a meditation on justice and political governance, and a searching portrait of three men caught in a deadly triangle. Billy is the handsome innocent, Claggart his cruel tormentor, and Captain Vere the man who must judge in the conflict between them. The narrative is variously interpreted in Biblical terms, or in terms of representations of male homosexual desire and the mechanisms of prohibition against this desire. His other great novellas Benito Cereno, The Encantadas and Bartelby the Scrivener (all in this collection) show Melville as a master of irony, point-of-view, and tone. These fables ripple out in nearly endless circles of meaning and ambiguities. Artistically, the novella is often unified by the use of powerful symbols which hold together the events of the story. The novella requires a very strong sense of form – that is, the shape and essence of what makes it distinct as a literary genre. It is difficult to think of a great novella which has not been written by a great novelist (though Kate Chopin’s The Awakening might be considered an exception). Another curious feature of the novella is that it is almost always very serious. It’s equally difficult to think of a great comic novella – though Saul Bellow’s excellent Seize the Day has some lighter moments.

Artistically, the novella is often unified by the use of powerful symbols which hold together the events of the story. The novella requires a very strong sense of form – that is, the shape and essence of what makes it distinct as a literary genre. It is difficult to think of a great novella which has not been written by a great novelist (though Kate Chopin’s The Awakening might be considered an exception). Another curious feature of the novella is that it is almost always very serious. It’s equally difficult to think of a great comic novella – though Saul Bellow’s excellent Seize the Day has some lighter moments. Seize the Day (1956) focusses on one day in the life of one man, Tommy Wilhelm. A fading charmer who is now separated from his wife and his children, he has reached his day of reckoning and is scared. In his forties, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. Some people might wish to argue that this is a short novel, but it is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a novella. It is now generally regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works, even though he went on to write a number of successful and much longer novels – for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976.

Seize the Day (1956) focusses on one day in the life of one man, Tommy Wilhelm. A fading charmer who is now separated from his wife and his children, he has reached his day of reckoning and is scared. In his forties, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. Some people might wish to argue that this is a short novel, but it is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a novella. It is now generally regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works, even though he went on to write a number of successful and much longer novels – for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976. Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1897) is a classic novella, and a ghost story which defies easy interpretation. A governess in a remote country house is in charge of two children who appear to be haunted by former employees who are now supposed to be dead. But are they? The story is drenched in complexities – including the central issue of the reliability of the person who is telling the tale. This can be seen as a subtle, self-conscious exploration of the traditional haunted house theme in Victorian culture, filled with echoes of sexual and social unease. Or is it simply, “the most hopelessly evil story that we have ever read”? This collection also includes James’s other ghost stories – Sir Edmund Orme, Owen Wingrave, and The Friends of the Friends.

Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1897) is a classic novella, and a ghost story which defies easy interpretation. A governess in a remote country house is in charge of two children who appear to be haunted by former employees who are now supposed to be dead. But are they? The story is drenched in complexities – including the central issue of the reliability of the person who is telling the tale. This can be seen as a subtle, self-conscious exploration of the traditional haunted house theme in Victorian culture, filled with echoes of sexual and social unease. Or is it simply, “the most hopelessly evil story that we have ever read”? This collection also includes James’s other ghost stories – Sir Edmund Orme, Owen Wingrave, and The Friends of the Friends. The Aspern Papers (1888) also by Henry James, is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s private correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer seeks a husband for her plain niece, whereas the potential purchaser of the letters she possesses is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who wins out? Henry James keeps readers guessing until the very end. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in the outcome. This collection of stories also includes The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion which is another classic novella.

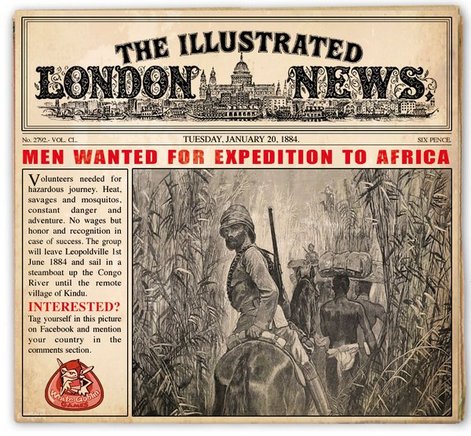

The Aspern Papers (1888) also by Henry James, is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s private correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer seeks a husband for her plain niece, whereas the potential purchaser of the letters she possesses is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who wins out? Henry James keeps readers guessing until the very end. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in the outcome. This collection of stories also includes The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion which is another classic novella. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of late nineteenth century imperialism and the colonial process. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement. It is certainly regarded as a classic of the novella form, and a high point of twentieth century literature – even though it was written at its beginning. This volume also contains the story An Outpost of Progress – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’. The differences between a story and a novella are readily apparent here if you read both texts and compare them.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of late nineteenth century imperialism and the colonial process. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement. It is certainly regarded as a classic of the novella form, and a high point of twentieth century literature – even though it was written at its beginning. This volume also contains the story An Outpost of Progress – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’. The differences between a story and a novella are readily apparent here if you read both texts and compare them. Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis is the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. His family are bewildered, find it difficult to deal with him, and despite the good human intentions struggling underneath his insect carapace, they eventually let him die of neglect. He eventually expires with a rotting apple lodged in his side. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s other masterly transformations of the short story form – ‘The Great Wall of China’, ‘Investigations of a Dog’, ‘The Burrow’, and the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’.

Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis is the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. His family are bewildered, find it difficult to deal with him, and despite the good human intentions struggling underneath his insect carapace, they eventually let him die of neglect. He eventually expires with a rotting apple lodged in his side. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s other masterly transformations of the short story form – ‘The Great Wall of China’, ‘Investigations of a Dog’, ‘The Burrow’, and the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’. Ethan Frome

Ethan Frome The Age of Innocence

The Age of Innocence The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth The Reef

The Reef

Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All essays are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work.

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All essays are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work.