tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot summary

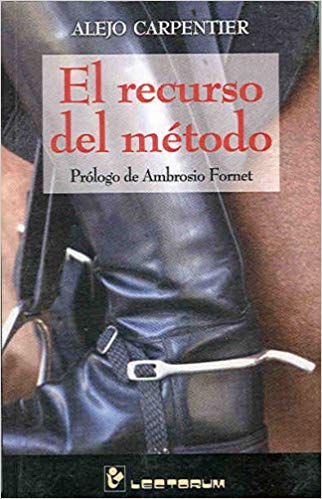

Reasons of State (1974) first published as El recurso del metodo has a curious history. It was written as the result of a bet between Alejo Carpentier and Gabriel Garcia Marquez – both of them Nobel prizewinners. Marquez produced The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975) and Carpentier wrote Reasons of State. Both novels deal with an issue which still blights Latin-America today – political stranglehold by dictatorships. As literary works they owe a great deal to El senor presidente (1946) which was the first novel to deal with this issue, written by the Guatemalan writer Miguel Asturias, an equally distinguished predecessor . The English translation is by Francis Partridge, one of the last survivors of the Bloomsbury Group.

Reasons of State – commentary

Magical realism

Carpentier is one of the many Latin-American writers who have employed the technique of ‘magical realism’ – a term that he coined himself. This is an approach to fictional narratives that combines traditional realism with elements of fantasy, exaggeration, and the supernatural.

In Reasons of State for instance, the president from his Parisian embassy socialises with other fictional characters such as the distinguished academician, his daughter and his secretary, Peralta. Combined with this fictional world, he is also acquainted with real historical figures such as the Italian fascist and poet Gabriele D’Dannunzio (1863-1938).

There is therefore a close mixture of the fictional with the ‘real’, historical worlds. But he is also connected in the narrative with people such as Elstir (a painter), Vinteuil (a composer), Morel (a violinist) who are fictional characters from Marcel Proust’s great novel Remembrance of Things Past. This brings a second level of fictionality to the narrative – with the subject of one fictional text appearing in another. This is sometimes known as ‘intertextuality’.

For good measure, the president is also personally acquainted with Reynaldo Hahn, the Venezuelan composer who was a close friend of Proust. The narrative therefore switches between a fictional realism of its own making, references to real historical events and people, and the inclusion of elements from a parallel world of cultural aesthetics and history.

Narrative mode

It should be clear from the outset that the narrative is delivered in a mixture of first-person and third-person narrative modes. The novel begins with the president’s thoughts and feelings as his day begins in the Parisian embassy:

I’ve never been able to sleep in a rigid bed with a mattress and bolster. I have to curl up inside a rocking hammock, to be cradled in its corded network. Another swing and a yawn, and with another swing I get my legs out and hunt about with my feet for my slippers which I have lost in the pattern of the Persian carpet.

But gradually this first-person account becomes a third-person presentation of events delivered in conventional manner, as if by an anonymous omniscient narrator. These events are largely concerned with revealing the President’s scandalous and hypocritical behaviour:

“The cunt! The son of a bitch!” yelled the Head of State hurling the cables to the ground. “I’ve not finished reading it,” said the Cholo Mendoza, picking up the papers. The movement had spread to three provinces of the North and threatened the Pacific zone.

Carpentier manages these transitions very skilfully, but this technique does pose some aesthetic problems. There is a blurring and eventually very little distinction between the two modes. The result is that many lengthy passages of narrative, packed with literary, historical, cultural, and philosophical references, have the appearance of representing the president’s point of view.

We now know that many dictators can be culturally sophisticated at the same time as being social barbarians who countenance torture and the savage repression of all criticism. But somehow the range and depth of cultural references attributed to the president never seem persuasive.

There is also the problem (shared with Carpentier’s other novels) of a disruptive volume of material concerned with music and architecture. These are both subjects Carpentier studied as an undergraduate and has written on extensively, but their appearance in Reasons of State constitute what elsewhere would be considered digressions. They are not fundamentally linked to the main themes of the novel.

The main theme

The principal subject of the novel is obviously the life, thought processes, and behaviour of a dictator. The novel traces his desperate attempts the cling to power, his decline, exile, and death. In this sense it follows the tradition established by Miguel Asturias with Mister President (1946) and is similar to The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975) by Gabriel Garcia Marquez and The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962) by Carlos Fuentes. All of them have catalogued the disruptive and tyrannical effects of Central American regimes lacking democracy – in Guatemala, Venezuela, and Mexico – though all of them have chosen to write about fictional, imaginary, and un-named countries.

However the underlying theme of Carpentier’s novel (as in many of his other works) is the tension and contradictions between native Latin-American history and the traditional western culture that has arisen out of Europe. Carpentier was born in Switzerland and educated largely in Paris, where he began his literary career in the 1920s. But his family also spent a lot of time in Havana, and he was a founding member of the Cuban Communist Party in 1921.

This is not to suggest that he suffered from ‘divided loyalties’ but to point out his abiding attempts to fuse the two very different cultures he had absorbed. His 1953 novel The Lost Steps deals very explicitly with this theme.

Reasons of State is interesting because he attributes a great deal of this interest in European culture to the President himself. This presents the reader with a certain problem of fictional credibility. We are asked to believe that this cruel and vulgar man is also a connoisseur of fine art, poetry, and opera. He abuses women, he is an alcoholic, an embezzler, and he rules by torture and executions; but we are expected to accept that he is also an enthusiast for classical music, painting and poetry, and a close friend of Reynaldo Hahn.

Readers will make up their own minds if he is a coherent and credible character or not. But there are two further points which might be made about this contradiction or imbalance. First, it might be said that Carpentier is forcing his own cultural enthusiasms into the novel – at all costs. Second, it could be said that despite the president’s unpleasant behaviour, Carpentier is in an an odd sense writing about himself.

It is in this sense that the contradiction between political mis-rule and cultural sophistication (the Latin-America/European divide) is the theme of the novel, as distinct from its overt subject, which is the decline and fall of a dictator.

Reasons of State – study resources

Reasons of State (2013) – Amazon UK

El recurso del metodo (2009) – Amazon UK

Reasons of State (2013) – Amazon US

El recurso del metodo (2009) – Amazon US

Alejo Carpentier: The Pilgrim at Home (2014) – Kindle

Reasons of State – plot summary

ONE

The president of an un-named Latin-American country wakes up in his Paris residence recalling a visit to a high-class brothel the previous night. He also reflects on his friendship with Gabriele D’Annunzio. There is a visit by a right-wing French academician, offering the president’s daughter Ofelia an introduction to Cosima Wagner. The academician sponges on the president by selling him some ‘rare’ manuscripts. Suddenly an ambassador arrives with news of a military uprising back home. There is an immediate council of war.

TWO

Arms are purchased in the USA with money from concessions ceded to the United Fruit Company. The president and his entourage sail to Havana incognito. Arriving in the home country, the president cracks down on protesting students and workers.

After a day’s military action the president and his entourage shelter from tropical storms in a cave, where they discover pre-Colombian embalmed bodies in urns. Next day they cross the Rio Verde, but the enemy has retreated. The rebel general Galvan is pursued, cornered, and executed.

In Nueva Cordoba the president and his men lay siege to a town which at first capitulates, but when resistance begins the president’s army slaughter the population. He then returns to the capital where a rigged election reaffirms his position. However, he is suffering from a frozen right arm and returns to France for treatment.

THREE

On arrival in Paris he is shunned by all his old contacts. The French press has reported all the atrocities in Nueva Cordoba. Only the reactionary academician shows any sympathy and excuses his ‘excesses’. In exchange for bribes the academician arranges for a press campaign flattering to the President. In the midst of ensuing confusion, the First World War breaks out.

In the lull before fighting begins, the president looks down on Europe and bolsters his flagging confidence with reflections on the profusion of religious Virgin saints in Latin-America. Then news arrives of a treacherous revolt by his minister of war, General Hoffman.

The President prepares for departure with a visit to a brothel. He realises he will have no convincing arguments to offer back home. He decides to attack German culture and promote Latinism in an attempt to curry popular support. His secretary tries to tempt him to remain in Paris, but he has grandiose notions of ‘Destiny’.

FOUR

General Hoffman is deserted by his troops and dies falling into a swamp. The president then goes on holiday to his seaside retreat. News of German atrocities in the war begin to appear, which the president cannot reconcile with the peaceful German colony living in the capital.

The European war brings prosperity to the country. The president decides to establish a national capitol, and architectural contests are held. A huge naked female statue is commissioned, but it turns out to be too big for its setting.

When the Germans torpedo an American ship, it brings the USA into the war. Amidst ridiculous propaganda about the comforts of the trenches, the president despatches troops. The capitol is completed and inaugurated with a lavish banquet, but the celebrations are followed by a bomb attack on the palace. The president immediately orders repressive measures against the university, teachers, students, bookshops, and the working public. The common element is identified as communism, which the president does not understand. But suddenly the European war ends.

There is an elaborate opera season which ends with another bomb attack. A model prison is built. The price of sugar collapses. Banks close. A period of celebratory carnival merges into armed revolt – which is put down with extreme repression, torture, and executions.

FIVE

North American influence grows and Europe is seen as chaotic and backwards. When the New York Times publishes a scathing critique of the country the national press merely responds with tabloid reports of sensational domestic crimes. Holy week is replaced by Santa Claus and a commercial Christmas.

Strikes begin, followed by the appearance of a radical bulletin Liberation. A spate of public misinformation ensues. Everything is blamed on a single trouble-maker – The Student. Someone is arrested and interrogated personally by the president, who cajoles then threatens him. The interview is cut short by an explosion.

The economy collapses and the city deteriorates. Strikes continue in the provinces. The presence of the USA grows. There is a general strike, to which the president responds by machine-gunning closed shops. There is public demand for the abdication of the president. A rumour is spread that the president is dead. People emerge to celebrate, and are slaughtered by troops.

SIX

The following day order collapses completely. US marines land in the North and the president escapes in an ambulance, disguised as a patient. He is given shelter by the provincial US consul. The secretary Peralta deserts to the rebels.

The president waits anxiously to be smuggled away by speedboat to a US ship.

SEVEN

The president arrives back in Paris to find his residence full of modern art and his louche daughter partying. Former contacts are unavailable or dead. He laments the changes in modern life and finds solace only in the brothel.

The Mayorala buys exotic fruits and cooks native dishes in the house, which the president and even Ofelia enjoy. Meanwhile Dr Martinez assumes power back home and promises reforms. The Student meets delegates to an international socialist conference in Paris.

The president grows thinner, time goes by, and he lives in the past, recalling how he cheated the country economically. He begins to confuse past and present, loses the use of his legs, and eventually dies.

Reasons of State – characters

| — | the President, head of state, dictator of a central American country |

| Dr Peralta | his secretary |

| Ofelia | his spoiled self-indulgent daughter |

| Ariel | his son, ambassador to the US |

| Mayorala Elmira | his housekeeper |

| General Ataulfo Galvan | a rebel leader |

| Dr Martinez | a professor of philosophy and rebel leader |

| Colonel Walter Hoffman | the minister for war |

| Enoch Crowder | the US ambassador |

| The Student | a figure representing all youthful resistance |

© Roy Johnson 2018

More on Alejo Carpentier

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Samuel Beckett began writing in the 1930s, and was deeply influenced in his early period by James Joyce, for whom he worked briefly as secretary. He was also influenced by the literary developments of the avant-garde modernist movement and both the existentialist and absurdist tendencies in cultural life which arose just before and intensified after the second world war. However, after Joyce’s death in 1941 he began to develop a style of his own – a style which became more gaunt and sinewy to reflect his increasingly bleak view of life, which is witheringly unsentimental at its most generous and darkly tragic at its most powerful.

Samuel Beckett began writing in the 1930s, and was deeply influenced in his early period by James Joyce, for whom he worked briefly as secretary. He was also influenced by the literary developments of the avant-garde modernist movement and both the existentialist and absurdist tendencies in cultural life which arose just before and intensified after the second world war. However, after Joyce’s death in 1941 he began to develop a style of his own – a style which became more gaunt and sinewy to reflect his increasingly bleak view of life, which is witheringly unsentimental at its most generous and darkly tragic at its most powerful. Murphy is Samuel Beckett’s first novel, published in 1938. It was written in English, unlike many of his later works which were written in French then translated into English. It is the story of a work-shy man, wandering adrift in London, who believes that human desire can never be satisfied. He seeks to withdraw from life into a state of what he sees as catatonic bliss. Murphy’s fiancée Celia tries to humanise him by finding him a job working as a nurse in a mental institution, but he sees the insanity of the patients an attractive alternative to his conscious existence from which he cannot escape.

Murphy is Samuel Beckett’s first novel, published in 1938. It was written in English, unlike many of his later works which were written in French then translated into English. It is the story of a work-shy man, wandering adrift in London, who believes that human desire can never be satisfied. He seeks to withdraw from life into a state of what he sees as catatonic bliss. Murphy’s fiancée Celia tries to humanise him by finding him a job working as a nurse in a mental institution, but he sees the insanity of the patients an attractive alternative to his conscious existence from which he cannot escape. Watt Beckett’s second novel was written during World War Two (1942-1944), while he was hiding from the Gestapo in Provence in southern France. It was first published in English in 1953 and tells a semi-incoherent story of Watt’s journey to become the manservant of a Mr Knott, and his struggle to understand the house they live in. It’s written with some of Beckett’s characteristically deadpan humour and quasi-philosophic jokes. He also uses deliberately unidiomatic language and pokes fun at contemporary figures and institutions. Watt has previously appeared in editions that are littered with major and minor errors. The new Faber edition offers for the first time a corrected text based on a scholarly appraisal of the manuscripts and their textual history.

Watt Beckett’s second novel was written during World War Two (1942-1944), while he was hiding from the Gestapo in Provence in southern France. It was first published in English in 1953 and tells a semi-incoherent story of Watt’s journey to become the manservant of a Mr Knott, and his struggle to understand the house they live in. It’s written with some of Beckett’s characteristically deadpan humour and quasi-philosophic jokes. He also uses deliberately unidiomatic language and pokes fun at contemporary figures and institutions. Watt has previously appeared in editions that are littered with major and minor errors. The new Faber edition offers for the first time a corrected text based on a scholarly appraisal of the manuscripts and their textual history. The Trilogy This is the famous trilogy that is generally regarded as the pinnacle of Beckett’s work as an experimental novelist. He was pushing the developments of modernism, existentialism, and absurdism as far as they would go. The three novels follow the bleak logic of Beckett’s move away from movement and life, towards stasis and death. Molloy (1951) is set in an indeterminate place and comprises the inner monologues of Molloy and a private detective called Moran. Both live in a state of semi-absurdity and seem almost to merge into the same person as they lose bodily mobility and end up using crutches. Malone Dies (1951) is the story of an old man who is confined to bed in a hospital or an asylum (he is not sure which). All notions of conventional plot or logical sequences of events are abandoned. The narrative is merely Malone’s obsession with the trivia of his existence, stripped of all physical effects except an exercise book and a pencil that is getting shorter and shorter. The Unnameable (1953) takes these experiments in prose fiction one stage further. It concerns a person with no name who lives under an old tarpaulin sheet. He is not even sure if he is dead or alive – and neither are we.

The Trilogy This is the famous trilogy that is generally regarded as the pinnacle of Beckett’s work as an experimental novelist. He was pushing the developments of modernism, existentialism, and absurdism as far as they would go. The three novels follow the bleak logic of Beckett’s move away from movement and life, towards stasis and death. Molloy (1951) is set in an indeterminate place and comprises the inner monologues of Molloy and a private detective called Moran. Both live in a state of semi-absurdity and seem almost to merge into the same person as they lose bodily mobility and end up using crutches. Malone Dies (1951) is the story of an old man who is confined to bed in a hospital or an asylum (he is not sure which). All notions of conventional plot or logical sequences of events are abandoned. The narrative is merely Malone’s obsession with the trivia of his existence, stripped of all physical effects except an exercise book and a pencil that is getting shorter and shorter. The Unnameable (1953) takes these experiments in prose fiction one stage further. It concerns a person with no name who lives under an old tarpaulin sheet. He is not even sure if he is dead or alive – and neither are we. The Expelled This collection of four stories or nouvelles represents work which dates from 1945, though they were all published much later, in French and then in English. Full contents: The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, and First Love. All the stories make use of a first-person narrator, and exploit its potential for expressing the frailties of human memory, the inability to distinguish the past from the present, and even a profound doubt concerning the purpose of life itself. The stories document the human condition of an unstoppable progress towards death.

The Expelled This collection of four stories or nouvelles represents work which dates from 1945, though they were all published much later, in French and then in English. Full contents: The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, and First Love. All the stories make use of a first-person narrator, and exploit its potential for expressing the frailties of human memory, the inability to distinguish the past from the present, and even a profound doubt concerning the purpose of life itself. The stories document the human condition of an unstoppable progress towards death. How It Is Published in French in 1961, and in English in 1964, this presents a novel in three parts, written in short paragraphs, which tell of a narrator lying in the dark, in the mud, repeating his life as he hears it uttered – or remembered – by another voice. Told from within, from the dark, the story is tirelessly and intimately explicit about the feelings that pervade his world, but fragmentary and vague about all else therein or beyond. The novel counts for many readers as Beckett’s greatest accomplishment in the prose narrative form. It is also his most challenging work, both stylistically and for the radical pessimism of its vision, which continues the themes of reduced circumstance, of another life before the present, and the self-appraising search for an essential self.

How It Is Published in French in 1961, and in English in 1964, this presents a novel in three parts, written in short paragraphs, which tell of a narrator lying in the dark, in the mud, repeating his life as he hears it uttered – or remembered – by another voice. Told from within, from the dark, the story is tirelessly and intimately explicit about the feelings that pervade his world, but fragmentary and vague about all else therein or beyond. The novel counts for many readers as Beckett’s greatest accomplishment in the prose narrative form. It is also his most challenging work, both stylistically and for the radical pessimism of its vision, which continues the themes of reduced circumstance, of another life before the present, and the self-appraising search for an essential self. Company These four last prose fictions span the final decade of Beckett’s life. In the title sytory a solitary listener lying in darkness calls up images from a past life. Ill Seen Ill Said is a meditation on an old woman living out her final days in an isolated cottage, watched over by a dozen mysterious sentinels. In Worstward Ho, a breathless speaker unravels the sense of life, acting out the repeated injunction to ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ Stirrings Still was published in the Guardian a few months before Beckett’s death in 1989. It is his last prose work and testament. The Faber edition also includes several short prose texts (Heard in the Dark I & II, One Evening, The Way, Ceiling) which represent works in progress or fragments composed around the same time as his final writing.

Company These four last prose fictions span the final decade of Beckett’s life. In the title sytory a solitary listener lying in darkness calls up images from a past life. Ill Seen Ill Said is a meditation on an old woman living out her final days in an isolated cottage, watched over by a dozen mysterious sentinels. In Worstward Ho, a breathless speaker unravels the sense of life, acting out the repeated injunction to ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ Stirrings Still was published in the Guardian a few months before Beckett’s death in 1989. It is his last prose work and testament. The Faber edition also includes several short prose texts (Heard in the Dark I & II, One Evening, The Way, Ceiling) which represent works in progress or fragments composed around the same time as his final writing. Works for Radio

Works for Radio Complete Dramatic Works This one-volume compendium contains all of Beckett’s dramatic texts written between 1955 and 1984. It includes both the major dramatic works and the shorter and more compressed texts he created for the stage and for radio. Full contents: Waiting for Godot, Endgame, Happy Days, All That Fall, Acts Without Words, Krapp’s Last Tape, Roughs for the Theatre, Embers, Roughs for the Radio, Words and Music, Cascando, Play, Film, The Old Tune, Come and Go, Eh Joe, Breath, Not I, That Time, Footfalls, Ghost Trio,…but the clouds…, A Piece of Monologue, Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, Quad, Catastrophe, Nacht und Traume, What Where.

Complete Dramatic Works This one-volume compendium contains all of Beckett’s dramatic texts written between 1955 and 1984. It includes both the major dramatic works and the shorter and more compressed texts he created for the stage and for radio. Full contents: Waiting for Godot, Endgame, Happy Days, All That Fall, Acts Without Words, Krapp’s Last Tape, Roughs for the Theatre, Embers, Roughs for the Radio, Words and Music, Cascando, Play, Film, The Old Tune, Come and Go, Eh Joe, Breath, Not I, That Time, Footfalls, Ghost Trio,…but the clouds…, A Piece of Monologue, Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, Quad, Catastrophe, Nacht und Traume, What Where. The Cambridge Companion to Beckett

The Cambridge Companion to Beckett

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy Far from the Madding Crowd

Far from the Madding Crowd The Return of the Native

The Return of the Native