tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

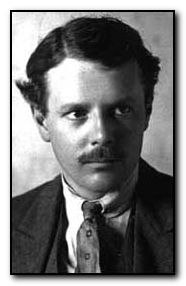

Glory was written in the later part of 1930 when Vladimir Nabokov was living in Berlin, exiled from his native Russia. The Novel originally had a working title ofRomanticheskiy vek (Romantic Times) but this was discarded in favour of Podvig (‘gallant feat’ or ‘high deed’) under which title it was first serialized in a Russian emigré journal in Paris 1932. Like his other early works, it was published under the pen name of “V. Sirin” which he had adopted earlier to distinguish himself from his father, who was also called Vladimir Nabokov and was a prominent writer and politician.

Nabokov later translated the novel into English in collaboration with his son Dmitri as part of the post-Lolita refurbishment of his earlier works that had been written in Russian and were largely unknown to readers in the English-speaking world. It appeared simultaneously in America and the UK in 1971.

Glory – critical commentary

The biographical element

Vladimir Nabokov was adept at transforming the events of his own life into the materials of his fiction and non-fiction works. His first novel Mary (1926) is a metaphoric reflection of separation from his native Russia (as it then was). He used the details of his own life in the semi-autobiographical novel The Real Life of Sebastian Knight in 1938 – his first novel written in English. His later non-fictional Speak Memory (1967) covers memoirs of individuals and events from his ‘Russian years’, and he continued to mine the same subject matter through the comic burlesque of Pale Fire (1962) to the almost self-parodic Look at the Harlequins (1974).

It is strange but true that having lost a personal fortune as a result of the Russian revolution, having been separated from his home and culture, endured exile, and been forced to live in countries where he did not feel comfortable (Germany) – despite all this, Nabokov’s work is full of positive, optimistic, and even ecstatic evocations of everyday life. He seems to find life-affirming responses and a persistent delight in the aesthetics of common events – the visual textures of busy streets, the atmospheric effects of weather systems, and the colour schemes of a sunset. Martin Edelweiss, the protagonist of Glory is the concentration of this pleasure in phenomena into one character. His exile from his native land is never seen in terms of regret or a peeved sense of injustice. He experiences epiphanies and ‘moments being’ wherever he happens to find himself:

An automobile advertisement, brightly beckoning in a wild, picturesque gorge from an absolutely inaccessible spot on an alpine cliff thrilled him to tears. The complaisant and affectionate nature of very complicated and very simple machines, like the tractor or the linotype, for example, induced him to reflect that the good in mankind was so contagious that it infected metal. When, at an amazing height in the blue sky above the city, a mosquito-sized airplane emitted fluffy, milk-white letters a hundred times as big as it, repeating in divine dimensions the flourish of a firm’s name, Martin was filled with a sense of marvel and awe.

His movements are a close approximation to Nabokov’s own – retreat from a privileged home in Russia, exile in Europe; material support from a rich uncle; education at Cambridge University; coaching tennis as a spare time job in Berlin, which is exactly what Nabokov was doing at the time he wrote the novel.

The conclusion

When Nabokov wrote the novel in 1930 his personal biography had reached no further than literary ambitions and spare time work as an exile in Berlin – so the parallels between Nabokov and his protagonist Martin Edelweiss are quite exact. But he decided not to make Martin into “an artist, a writer” – so how is Martin to find ‘fulfilment’ (which was another possible title for the novel)?

From the very early chapters of the narrative Martin has been fascinated by fairy tale-like scenes of woodlands into which he sees himself disappearing. He has such a framed picture in his bedroom; he sees a similar landscape in Provence; and ultimately he disappears figuratively into a woodland scene he imagines waiting at the Latvian border.

Similarly, throughout the novel, Martin has been touched emotionally by Russian connections – its people, its intellectual and literary culture, and even its cuisine. He has a deep-seated yearning for connections with his homeland of which he is only half conscious – seeing his escapade of re-crossing the border almost as a romantic dream. Nabokov himself on the other hand made no secret of his understandable yearning for his Russian heritage, and his clear understanding that it was impossible to ‘go back’ to it.

The ambiguity of Nabokov’s own personal feelings is perhaps reflected in the fact that he sends his protagonist Martin on an expedition back across the border – but we do not know if he gets there or not. We do not know if he is killed by the secret agents, the border guards, or the spies he knows will line his route – or if he simply ‘disappears’ into mother Russia.

This is a logically explicable ending to the trajectory of Martin’s life, but it does not make for a very satisfactory conclusion to a novel. We expect some sort of resolution or ‘closure’ to events. Having a protagonist simply ‘vanish’ from the proceedings of the narrative is not good creative practice. The absence of any conceptual structure reduces the narrative to what is not much more than a well decorated memoir, an autobiographical sketch, or a chronological record of life in exile. It is clever and well-articulated picture, but it is not constructed in a manner that produces a satisfying whole.

Glory – study resources

![]() Glory – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Glory – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Glory – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Glory – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Podvig – Russian original – Amazon UK

Podvig – Russian original – Amazon UK

![]() Podvig – Russian original – Amazon US

Podvig – Russian original – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Amazon UK

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years – Biography: Vol 1

Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years – Biography: Vol 1

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: American Years – Biography: Vol 2

Vladimir Nabokov: American Years – Biography: Vol 2

![]() Zembla – the official Nabokov web site

Zembla – the official Nabokov web site

![]() The Paris Review – Interview with Vladimir Nabokov

The Paris Review – Interview with Vladimir Nabokov

![]() Nabokov’s first English editions – Bob Nelson’s collection

Nabokov’s first English editions – Bob Nelson’s collection

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study materials

Glory – principal characters

| Martin Edelweiss | a young Russian exile |

| Sonia Edelweiss | his mother |

| Henry Edelweiss | his rich uncle, later his stepfather |

| Alla Chernosvitove | a flirtatious poet |

| Darwin | Martin’s bosom friend at Cambridge |

| Archibald Moon | gay professor of Russian at Cambridge |

| Mihail Platonovich Zilanov | a liberal politician and activist |

| Mrs Zilanov | Martin’s Russian landlady in London |

| Sonia Zilanov | her flirtatious but fickle young daughter |

| Vadim | student at Cambridge – a practical joker |

| Alexandr Naumovich Igolevich | a Russian patriot |

| Bubnov | a Russian emigre writer |

| Guzinov | a Russian exile in Lausanne |

Glory – chapter summaries

1 The background of Martin’s Swiss grandfather and his Anglophile mother Sofia.

2 Martin’s mother reads to him English fairy tales. He dreams imaginatively of entering the forests in paintings and stories.

3 Martin’s parents separate, and shortly afterwards his father dies.

4 Martin is full of stoical self control, but he has romantic dreams of courage and heroic deeds.

5 On summer holiday in the Crimea he is capable as a teenager of experiencing transcendental ‘moments of being’.

6 This experience evokes memories of childhood holidays via overnight train journey to Biarritz.

7 In 1919 Martin and his mother escape from the revolution, sailing from the Crimea to Constantinople.

8 On board ship he is forced into the company of businessman Chernosvitov and his flirtatious wife the poet Alla, with whom Martin falls in love.

9 In Greece Alla and Martin become lovers, and he has his first ‘peek into paradise’.

10 Martin and his mother sail on to Marseilles and then travel to Lausanne, where they stay with his rich uncle Henry.

11 Martin wonders romantically what form his future instances of happiness will take. Arriving in London, he spends a night with a prostitute, who robs him the next morning.

12 In London his knowledge of English culture suddenly seems out of date. He lodges with family friends, the Zilanovs.

13 At Cambridge University he is forced to learn the conventions and rituals of undergraduate life. He befriends Darwin, to whom he embellishes his life experiences.

14 Darwin is an individualist, a veteran of the first World war who has published a collection of short stories.

15 Martin is attracted to various subjects of study, but finally chooses Russian history and literature.

16 Archibald Moon, Martin’s tutor, is an eccentric English Russophile. They receive Mrs Zilanov and her prickly daughter Sonia for afternoon tea.

17 They are joined by Vadim, a raffish undergraduate who is given to practical jokes, slang, and obscenities.

18 At the Christmas vacation Martin visits his mother in Switzerland, where because of the snow he thinks of himself as back in Russia.

19 Martin calls on Mihail Zilanov in London, who talks to him about his father’s death.

20 Martin feels awkward in Sonia’s presence. She behaves in a cavalier way to his friend Darwin. Martin wants to travel, but his uncle Henry says he must wait.

21 Whilst climbing in Switzerland Martin has a fall and a terrifying experience on a narrow ledge. He calls on the Zilanovs, where there has been a death in the family.

22 They are joined by Igolevich, who imparts terrible news from Russia, which rouses strange feelings in Martin that he does not understand. He has a nocturnal meeting with Sonia, who gets into his bed but rejects his physical advances.

23 After the vacation Martin discovers that Moon is a homosexual. He feels jealous of Darwin’s relationship with Sonia, and still dreams of performing heroic deeds.

24 Martin’s mother marries his uncle Henry. Martin has an affair with Rose who works in a tea shop. She becomes pregnant.

25 The pregnancy is a lie, and Rose is bought off by Darwin. Martin continues to hanker after Sonia.

26 Martin feels that his. Imaginative reveries can be turned into reality, and he has one of making an ‘illegal, clandestine. expedition’. Martin plays football for Trinity College. Darwin proposes to Sonia, who refuses him.

27 The Zilanov family move to Berlin. Martin reproaches Sonia for her ill-treatment of Darwin. Punting on the Cam, Martin and Darwin have an argument ostensibly about Rose.

28 Martin and Darwin have a fisticuffs duel – which Martin realises is really about their rivalry over Sonia.

29 Having finished university, Martin is not sure what to do, but he hatches a dream to ‘explore a distant land’.

30 Martin is disappointed by the matter-of-fact letters he receives from Sonia. His uncle reproaches him for his lack of employment and ambition. He decides to go to Berlin.

31 Berlin has changed and there is a recession. Martin recalls his earlier visits. And meanwhile he works as a tennis coach.

32 Martin visits the Zilanov family and becomes acquainted with the expatriate. Russian community.

33 He mixes with the literary exile community who try to keep Russian culture alive.

34 Sonia continues her coquettish behaviour towards him, but she does join in his fantasy of Zoorlandia – an imaginary distant northern country.

35 He continues his thankless pursuit of Sonia, but she treats him disdainfully, so he decides to leave Berlin.

36 He travels south through France by train, ambiguously outlining his plans to a fellow passenger.

37 Seeing lights in some distant hills, he gets off the train in the middle of the night.

38 Leaving his luggage at an inn, he walks to the nearest town Molignac.

39 He works as an agricultural labourer and has reveries that combine English and Russian culture. Despite the idyllic experience, his planned ‘expedition’ nags at his mind. He returns to his uncle and mother in Lausanne.

40 He successfully retraces his climb of the perilous mountain ledge from which he almost fell. Then he meets the ‘adventurer’ Gruzinov.

41 He borrows money from his uncle and announces his departure for Berlin.

42 He asks Gruzinov for advice about making an illegal entry to Russia – but feels that Gruzinov makes fun of him.

43 Despite his mother’s entreaties to stay, Martin takes leave of his uncle’s house.

44 He arrives in Berlin and is caught between the daring of his enterprise and the attractions of staying.

45 He calls on the Zilanovs and takes a very awkward farewell of Sonia

46 He dines on borsch in a Russian restaurant.

47 He visits Bubnov who is ill but still writing, then he goes to wait for Darwin at his hotel.

48 He tells Darwin his plans, but his friend refuses to believe he is serious. Some time later Darwin checks with the Zilanovs and even visits various embassies in Riga, but Martin has disappeared. Darwin breaks the news to Martin’s mother.

Vladimir Nabokov – web links

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex

Vladimir Nabokov at Mantex

Biographical notes, book reviews, tutorials, study guides, videos, web links, and essays on the Complete Short Stories.

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia

Vladimir Nabokov at Wikipedia

Biographical notes, list of major works, bibliography, and web links

![]() Lolita USA

Lolita USA

A ‘geographical scrutiny’ of Humbert and Lolita’s journey across America. Essay and photographic study by Dieter E. Zimmer.

![]() Vladimir Nabokov Writings – First Appearance

Vladimir Nabokov Writings – First Appearance

An illustrated collection of first editions in English. Photographs with bibliographical notes compiled by Bob Nelson

![]() Vladimir Nabokov at the Internet Movie Database

Vladimir Nabokov at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, plot, box office, trivia, continuity errors, and quiz.

![]() Zembla

Zembla

Biography, timeline, photographs, eTexts, sound clips, butterflies, literary criticism, online journal, scholarly essays, and an online annotated version of Ada – housed at Pennsylvania State University Library.

![]() Nabokov Museum

Nabokov Museum

A major collection housed in Nabokov’s old family home (now a museum) in St. Petersburg. – biography, photos, family home, videos in English and Russian.

© Roy Johnson 2016

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading.

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most important writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. This volume offers a concise and informative introduction into the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short-story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his world-view, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading. ![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

More on Vladimir Nabokov

More on literary studies

Nabokov’s Complete Short Stories

During Christmas dinner, whilst Pip is scared that someone will notice the missing pie. Police officers arrive and hunt through the marshes outside the village for escaped convicts. They accost the man helped by Pip, but when questioned about where he got the food and file, he claims he stole the items himself. The police take him off to the Hulk, a giant prison ship.

During Christmas dinner, whilst Pip is scared that someone will notice the missing pie. Police officers arrive and hunt through the marshes outside the village for escaped convicts. They accost the man helped by Pip, but when questioned about where he got the food and file, he claims he stole the items himself. The police take him off to the Hulk, a giant prison ship.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory. Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) was born into an upper middle-class family in Tehran, where his father (Lord Carnock) was the British ambassador to Persia. as it then was. He was educated at Wellington College then Balliol College Oxford, where he graduated with a third-class degree. He entered the diplomatic service in 1908 and was posted to Constantinople where he became a specialist in Balkan affairs. In 1910 he met

Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) was born into an upper middle-class family in Tehran, where his father (Lord Carnock) was the British ambassador to Persia. as it then was. He was educated at Wellington College then Balliol College Oxford, where he graduated with a third-class degree. He entered the diplomatic service in 1908 and was posted to Constantinople where he became a specialist in Balkan affairs. In 1910 he met