a critical examination of Nabokov’s collected stories

Nabokov’s Complete Stories is an analysis of the fifty collected tales included in Nabokov’s Dozen (1959), A Russian Beauty and Other Stories (1973), Tyrants Destroyed and Other Stories (1975), and Details of a Sunsetand Other Stories (1976).

In 1995 Nabokov’s son Dmitri edited and issued a single volume of Nabokov’s complete collected stories. This edition contained stories which had emerged since the author’s death and some very early works that Nabokov himself did not think were worth republishing. Studies and critiques of these earlier works are being added as a supplement here.

Part I – Apprentice Years: Stories 1924 – 1929

• A Matter of Chance

• Details of a Sunset

• The Thunderstorm

• Bachmann

• Christmas

• A Letter that Never Reached Russia

• The Return of Chorb

• A Guide to Berlin

• A Nursery Tale

• Terror

• The Passenger

• The Doorbell

• An Affair of Honour

• The Potato Elf

Part II – The European Master: Stories 1930 – 1939

• The Eye

• The Aurelian

• A Bad Day

• A Busy Man

• Terra Incognita

• Lips to Lips

• The Reunion

• Orache

• Music

• A Dashing Fellow

• Perfection

• The Admiralty Spire

• The Leonardo

• The Circle

• Breaking the News

• In Memory of L.I.Shigaev

• A Russian Beauty

• Torpid Smoke

• Recruiting

• A Slice of Life

• Spring in Fialta

• Cloud, Castle, Lake

• Tyrants Destroyed

• The Visit to the Museum

• Lik

• Vasiliy Shishkov

Part III – American Notes: Stories 1940 – 1951

• The Assistant Producer

• That in Aleppo Once…

• A Forgotten Poet

• Time and Ebb

• Conversation Piece

• Signs and Symbols

• The Vane Sisters

• Lance

• Conclusion

Additional Stories

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon UK

Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon UK

![]() Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon US

Vladimir Nabokov: The Collected Stories – Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2005

Vladimir Nabokov web links

Vladimir Nabokov greatest works

Vladimir Nabokov criticism

Vladimir Nabokov life and works

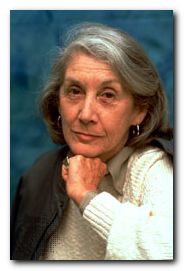

Nadine Gordimer (1923—2014) was born into a privileged white middle-class family in the Transvaal, South Africa. She began reading at an early age, and published her first story in a magazine when she was only fifteen. Her wide reading informed her about the world on the other side of apartheid – the official South African policy of racial segregation – and that discovery in time developed into strong political opposition to apartheid. She attended the University of Witwatersrand for one year. Her first book was a collection of short stories, The Soft Voice of the Serpent (1952). In addition to writing, she lectured and taught at various schools in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. She was awarded the Nobel prize for Literature in 1991.

Nadine Gordimer (1923—2014) was born into a privileged white middle-class family in the Transvaal, South Africa. She began reading at an early age, and published her first story in a magazine when she was only fifteen. Her wide reading informed her about the world on the other side of apartheid – the official South African policy of racial segregation – and that discovery in time developed into strong political opposition to apartheid. She attended the University of Witwatersrand for one year. Her first book was a collection of short stories, The Soft Voice of the Serpent (1952). In addition to writing, she lectured and taught at various schools in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. She was awarded the Nobel prize for Literature in 1991. The Conservationist (1974) concerns a white industrialist who farms his land (with native help) at the weekend and genuinely wants to make his presence a positive contribution. But most of all he wants to preserve his power and his privileged way of life – despite being surrounded by poverty and suffering. He just doesn’t understand that the indigenous population are the natural owners of the land, and the result is disastrous – for him.

The Conservationist (1974) concerns a white industrialist who farms his land (with native help) at the weekend and genuinely wants to make his presence a positive contribution. But most of all he wants to preserve his power and his privileged way of life – despite being surrounded by poverty and suffering. He just doesn’t understand that the indigenous population are the natural owners of the land, and the result is disastrous – for him. Jump Her development as a writer of short stories is wonderful. She starts off in modern post-Checkhovian mode presenting situations which have little drama but which invite the reader to contemplate states of being or moods which illustrate the ideologies of South Africa. Technically, Nadine Gordimer experiments heavily with point of view, narrative perspective, unexplained incidents, switches between internal monologue and third person narrative (rather like Virginia Woolf) and a heavy use of ‘as if’ prose where narrator-author boundaries become very blurred.

Jump Her development as a writer of short stories is wonderful. She starts off in modern post-Checkhovian mode presenting situations which have little drama but which invite the reader to contemplate states of being or moods which illustrate the ideologies of South Africa. Technically, Nadine Gordimer experiments heavily with point of view, narrative perspective, unexplained incidents, switches between internal monologue and third person narrative (rather like Virginia Woolf) and a heavy use of ‘as if’ prose where narrator-author boundaries become very blurred. Selected Stories As her work matured, her style and methods underwent a similar development to those of Virginia Woolf. Some of her stories became more lyrical, more compacted and symbolic, abandoning any semblance of conventional story or plot in favour of a poetic meditation on a theme. There are some stories which make enormous demands upon the reader. Sometimes on first reading it’s even hard to know what is going on. But gradually a densely concentrated image or an idea will emerge – the equivalent of a Joycean ‘epiphany’ – and everything falls into place. Her own collection of Selected Stories are UK National Curriculum recommended reading.

Selected Stories As her work matured, her style and methods underwent a similar development to those of Virginia Woolf. Some of her stories became more lyrical, more compacted and symbolic, abandoning any semblance of conventional story or plot in favour of a poetic meditation on a theme. There are some stories which make enormous demands upon the reader. Sometimes on first reading it’s even hard to know what is going on. But gradually a densely concentrated image or an idea will emerge – the equivalent of a Joycean ‘epiphany’ – and everything falls into place. Her own collection of Selected Stories are UK National Curriculum recommended reading.

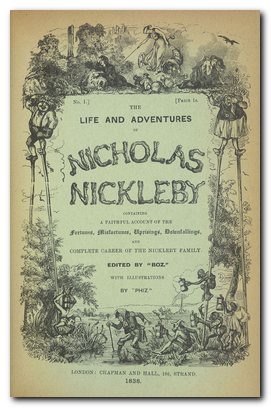

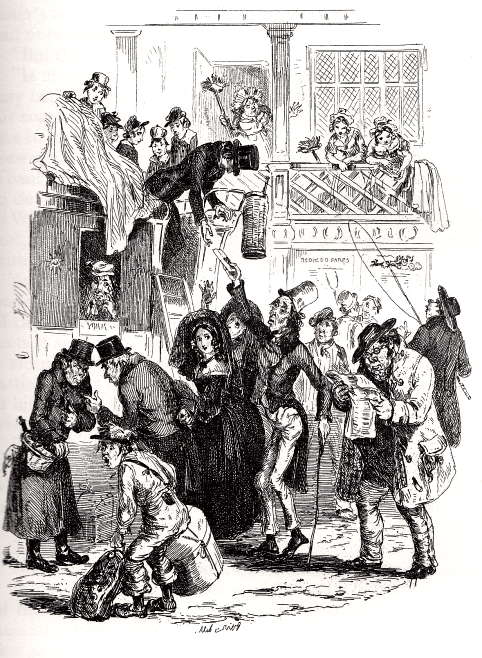

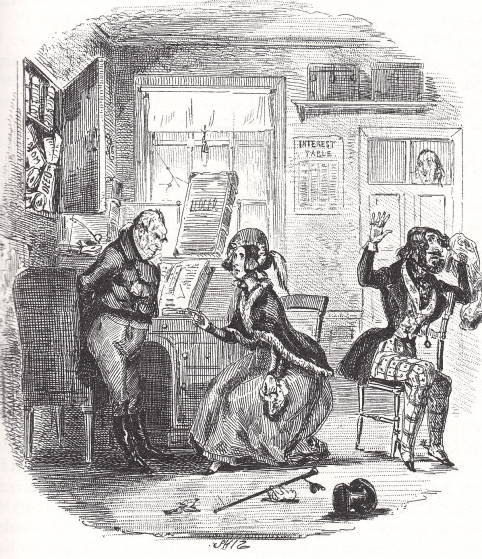

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and

In 1911 she launched herself into the London art world on the strength of a fifty pound advance on an inheritance from her uncle and a stipend of two shillings and sixpence a week from her aunts. There she socialised in the Cafe Royal with the likes of Augustus John, Walter Sickert, and