tutorial, commentary, study resources, further reading

The Woman in White (1861) was one of the best-selling novels of the nineteenth century. It not only sold in thousands of copies but also created what we would now call a ‘franchise boom’. It was so popular that manufacturers produced Woman in White perfumes and clothing, and proposals of marriage were made to the courageous (but fictitious) heroine Marian Halcombe.

The publication introduced two new elements into the novel genre. It was a ‘sensation novel’ or a ‘novel with a secret’ as they came to be known. It was also tightly plotted and intricately organised in a manner that makes powerful intellectual demands on the reader. And, it should be noted – it was structured and related by a multiplicity of narrative voices in a remarkably successful manner.

The Woman in White – a note on the text

The Woman in White first appeared as a serial in All the Year Round, the weekly newspaper owned and edited by Charles Dickens. The novel ran between November 1859 and August 1860, and enormously increased sales of the newspaper.

It then appeared in what (at that time) was a conventional three-volume format, published by Sampson Low, and was an immediate success. Its initial printing of 1,000 copies sold out on the first day, despite a relatively high cost of 31s 6d.

The success of the novel led to further editions and printings in America, Australia, France, and Germany. For all of these productions Wilkie Collins tweaked and supplemented the text. The most ‘stable’ and reliable version of the novel is generally considered to be the ‘New Edition’ created for the single-volume publication of the book in 1861.

For a full account of the composition, publication, and reception of the novel, see the bibliographic essay by John Sutherland in the Oxford World’s Classics edition of the book

The Woman in White – critical commentary

The detective novel

Wilkie Collins is often credited with the invention of the detective novel – which is not quite true. The first real detective hero in fiction was Auguste Dupin, the super-rationalist of Edgar Allen Poe’s stories, who solves crimes largely by a combination of creative imagination and what Poe called ‘ratiocination’. The second major fictional detective was Inspector Bucket in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House (1852) who is a superior sort of Scotland Yard dogged sleuth-investigator.

The Woman in White is in one sense a detective novel without a detective. The central character Walter Hartright acts as a form of solicitor-cum-sleuth. He assembles what we would now call ‘witness statements’- letters, depositions, diaries, and memoirs to provide a body of evidence supporting his case against the villains ‘Sir’ Percival Glyde and Count Fosco.

This ‘case’ never reaches a formal trial. We the readers are the unstated jury, and Walter‘s evidence proves the case he is making against the two accused men and their accomplice, the sinister Countess Fosco.

Wilkie Collins flags up at the start of the novel the originality of this quasi-legalistic approach – for which he justly deserves credit. The ‘hero’ Walter Hartright points out that his collection of personal testimonies will constitute the voices normally heard in a court of law:

Thus, the story here presented will be told by more than one pen, as the story of an offence against the laws is told in Court by more than one witness – with the same object, in both cases, to present the truth always in its most direct and most intelligible aspect, and to trace the course of one complete series of events, by making the persons who have been most closely connected with them, at each successive stage, relate their own experience, word for word.

Multiple narrators

Wilkie Collins’ genius lies in making his collection of narrators credible, yet partial, flawed, and even downright deceptive – yet he does so in such a manner that the reader can piece together a coherent account of what has taken place.

The framing narrative perspective comes from Walter Hartright, who is baffled by events, but is truthful in what he relates. Whilst absent from events, he hands over to Marian Halcombe, who is a more complex character. She is initially impressed by both Percival Glyde and Count Fosco, even though it will be clear to most readers that they are devious and villainous.

The housekeeper Eliza Michelson is even more gullible: she is taken in completely by Fosco’s oleaginous flattery. The solicitor Gilmore is accurate but short-sighted, and he too is taken in by Glyde and Fosco. The narrative even includes a supposedly full ‘confession’ from Fosco himself. This is a literary masterpiece (on Collins’ part) of lies, half-truths, self-justification, and evasiveness, all dressed up in his flamboyant, vainglorious style of speech and writing.

It is often observed that the use of multiple narrators had been pioneered by writers such as Tobias Smollett in Humphry Clinker (1771) and Emily Bronte in Wuthering Heights (1847) – but Wilkie Collins pushed this literary device along a few stages further.

In Fosco’s contributions to the narrative for instance, he throws up factual smokescreens, he lies, and he even offers taunting satirical comments on other people’s evidence. Both his entries in Marian’s diaries and his last-minute ‘confession’ are superb examples of Wilkie Collins’ multi-layered approach to the construction of a narrative.

Fosco is contributing to the account of events; he is passing comment on them; he is attempting to distort the record of what happened, and he is also mischievously aware of being an actor in the narrative of the drama – making him almost a self-conscious fictional character.

The sensation novel

Wilkie Collins is generally regarded as the inventor of the ‘sensation novel’ – and The Woman in White is seen as the first and classic example of this particular genre, the influence of which lingered until the end of the nineteenth century. At that later point its vogue in popular fiction was overtaken by the even more extreme Gothic horror story.

The sensation novel made its impact by introducing issues such as sexual scandal. murder, disguise, bigamy, madness, blackmail, fraud, theft, kidnapping, incarceration, and disputed wills. It also relied heavily on mysteries and secrets underpinning events – which is certainly true of The Woman in White, which has a number of mysteries, but ultimately rests on one Big Secret.

This is the fact that ‘Sir’ Percival Glyde is bogus throughout the whole novel – because he does not legitimately hold the title of Baronet. His parents are not married, and the legitimate title belongs to someone else. Glyde is a fraud – and that is the source of his Secret. He is guilty of false identity – technically ‘personification’

This leads to another typical element of the sensation novel – forgery. Glyde illegally inserts details of his parents’ non-existent marriage into the parish register. He does this for three reasons: he wishes to assume right to the Baronetcy; he wants to inherit the Fairlie estate; and he needs legitimacy to give himself the legal possibility of borrowing money against the Fairlie ‘name’.

Imprisonment

The Woman in White involves not just one but two instances of illegal imprisonment. Anne Catherick (The Woman) is placed in a lunatic asylum against her will by Glyde – because he fears she might reveal his Secret. She escapes, goes into hiding, and tries to warn Laura about him.

When Glyde learns that there has been contact between the two women, he assumes that his Secret has been revealed (which it has not) and he then imprisons his own wife in the asylum – but does so under Anne Catherick’s name. This is a sort of ‘double imprisonment’ for Laura.

Subsequent to this, as part of what we might now call ‘identity theft’, Anne Catherick (who dies) is buried not in her own name but in Laura’s.

The other shocking elements of ‘sensation’ should be fairly obvious to modern readers. Glyde becomes a psychologically and physically abusive husband to Laura; letters are intercepted, stolen, and re-written; a death certificate is forged; there is a great deal of spying; and Count Fosco and his sinister wife drug their victims using what he a euphemistically refers to as an interest in ‘chemistry’.

The legal problem

There is however something of a puzzling issue at the base of the plot line of The Woman in White. As a fake Baronet badly in need of money, the villain Glyde goes to extraordinary lengths to secure Anne’s inheritance of twenty thousand pounds. He will not marry her unless she agrees to the condition, and he has the gullible solicitor Gilmore draw up legal agreements to secure it.

Yet under the law obtaining at the time the novel is set (and was written) all of a woman’s property and money automatically passed into the control of the man she married. This was one of the scandalous iniquities of English law which was much debated and eventually changed with the passing of the Married Woman’s Property Act in 1882.

Even worse at that time, a woman ceased to be a legal or moral entity when she married. It was not until the Act of 1882 that these conditions were changed.

So there was no need for ‘Sir’ Percival Glyde to resort to solicitors: Laura’s money would come to him automatically – unless Collins was suggesting that Glyde’s false legal status could invalidate the process, but there is no consideration of this point in the text.

Characterisation

In terms of literary characterisation, The Woman in White poses some interesting problems. The positive characters – hero and heroines – are thin and unprepossessing, whereas some of the negative characters are quite vivid, memorable, and even amusing.

The protagonist and main narrator Walter Hartright is honourable, loyal, and indefatigable in his pursuit of the truth regarding the mystery. But as a character he is rather bland and unmemorable. Similarly, the ostensible ‘heroine’ of the novel, Laura Fairlie, is like a child’s doll. She might be pretty, but she is an agent who is acted upon but makes no positive impression of any kind.

Laura’s half-sister Marian starts out as a more interesting creation – with un-corsetted haunches and mannish behaviour – but this side of her character is not developed. She becomes merely the stoic tomboy who climbs onto a verandah in the rain, and eventually endures typhoid fever. The most interesting thing about her is that she ends up living in a ménage a trois with her married half sister and brother-in-law.

Yet amongst the negative characters, Wilkie Collins creates two inspired characters. The first is self-obsessed aesthete Frederick Fairlie who hides from the world behind a wall of hypochondria which is so advanced he would rather not be bothered talking to anybody, and wants doors closed quietly so as not to upset his nerves.

The acute nature of his avoidance of all responsibility becomes quite comic. He is a similar character to Horace Skimpole in Bleak House (1852) – a man who has elevated self-interest into a philosophy and an art form. When Count Fosco tries to reassure Fairlie that Marian’s typhoid fever is not contagious, he recoils with shock and horror:

Accept his assurances! I was never farther from accepting anything in my life. I would not have believed him on his oath. He was too yellow to be believed. He looked like a walking West-Indian-epidemic. He was big enough to carry typhus by the ton, and to dye the very carpet he walked on with scarlet fever.

The other stand-out character is his fellow villain Count Fosco, a fat, witty, sophisticated, larger-than-life character who is quite obviously not at all that he seems. He flatters everybody he meets, dabbles in ‘chemistry’ (which is his euphemism for poison) and has pet mice and birds about his person, He turns out to be not only a charlatan but a spy who in his ‘confession’ at the end of the novel gives a boastfully frank account of his criminality in a typically oblique fashion:

If Anne Catherick had not died when she did, what should I have done? I should, in that case, have assisted worn-out Nature in finding permanent repose. I should have opened the doors of the Prison of Life, and have extended to the captive (incurably afflicted in mind and body) a happy release.

The Woman in White – study resources

![]() The Woman in White – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

The Woman in White – Oxford Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Woman in White – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

The Woman in White – Oxford Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Woman in White – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Woman in White – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Woman in White – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Woman in White – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Woman in White – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

The Woman in White – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Woman in White – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

The Woman in White – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Woman in White – York Notes – Amazon UK

The Woman in White – York Notes – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Wilkie Collins – Kindle eBook

The Complete Works of Wilkie Collins – Kindle eBook

![]() The Woman in White – 1982 BBC film

The Woman in White – 1982 BBC film

The Woman in White – plot synopsis

The First Epoch

Artist Walter Hartright saves Professor Pesca from drowning at Brighton. Pesca passes on to Walter the request for a private tutor in drawing in Cumbria.

Walter meets the Woman in White late at night on Hampstead Heath. She has connections with Limmeridge House in Cumbria where he is going. She claims to have been ill-used by a Baronet, and has escaped from an Asylum.

Walter travels to Limmeridge House, meeting the shapely but mannish Marian Halcombe. He tells her about the Woman in White’s association with the house. He is interviewed by Frederick Fairlie who is an aesthete and a valetudinarian.

He meets Laura Fairlie and immediately falls in love with her. Marian reads from her mother’s letter and a connection is established between Laura and Anne Catherick (the Woman in White) because of similarities in their dress.

Marian explains to Walter that he must leave, because Laura is engaged to be married to Sir Percival Glyde. She produces an anonymous letter, warning Laura not to marry Glyde, who is a Baronet from Hampshire.

Walter meets Anne Catherick and her friend Mrs Clements in the graveyard. Anne has no father, and is at odds with her mother. At the mention of Sir Percival Glyde she goes into a seizure of fear.

Walter and Marian go to the farm where Anne is staying, but she has left the same morning. Sir Percival Glyde is the visitor expected at Limmeridge House.

The solicitor Gilmore arrives and reassures Walter that Glyde is completely honourable. Marian and Laura thank Walter for his help – and he leaves Limmeridge.

Glyde arrives and persuades Gilmore that he has acted on Mrs Catherick’s own wishes in ‘providing’ a private Asylum for her daughter Anne. He also persuades Marian to write to Mars Catherick for proof of his claim.

A response from Mrs Cathherick supports Glyde, who gives Laura every latitude in coming to her decision about the marriage. She asks for more time, and Gilmore supports her.

A week later Gilmore gets a letter saying Laura will marry Glyde before she is twenty-one. Glyde (who has no money) insists on receiving Laura’s twenty thousand pounds as part of the marriage settlement.

Gilmore appeals to Laura’s guardian Fairlie to let her retain the twenty thousand pounds, but Fairlie refuses to take any interest in the case.

Laura wishes to tell Glyde that she is in love with Walter, but Glyde refuses to call off the engagement, claiming he loves Laura all the more because of her fine principles.

Glyde prides himself on his absence of any jealous feelings. Laura capitulates, and Walter leaves for Honduras.

Glyde sets a date. Laura complies passively. Marian finds more and more positive qualities in Glyde, who is still searching for Anne. Marian has presentiments that something will prevent the marriage, but it takes place.

The Second Epoch

Six months later Marian has arrived at Blackwater Park; Walter is in Honduras; Gilmore is ill; and Laura is on honeymoon in Europe. Marian visits the ominous Black Lake, then finds Mrs Catherick’s dog which has been shot by the park keeper.

On return Laura will not discuss her new marriage, yet asks about Walter. Glyde is even more distant and short-tempered. Marian gives a positive account of the fat and sleek Count Fosco, with his pet birds and tame mice. Glyde’s solicitor Merriman suddenly arrives from London.

Marian overhears news of Glyde’s money problems. She and Laura suspect that Fosco knows the details. On an excursion to the Lake they discuss Crime and its detection. Glyde learns about Mrs Catherick’s dog and is alarmed.

Glyde wants Laura to sign a legal document but will not reveal its content. She refuses, and there is a violent disagreement. Marian writes to Gilmore’s office for advice, but Fosco reads the letter.

Laura reveals to Marian that she knows Glyde married her for her money, and that he has learned of her love for Walter. He threatens to persecute both of them. They think they see a woman walking round the Lake.

A solicitor’s letter from London recommends not signing the document. Marian dreams about Walter in Honduras. Laura meets a distraught and dying Anne in the boat house. Anne wants to impart Glyde’s ‘secret’ to her – but doesn’t.

Laura is due to meet Anne in the boat house, but is intercepted by Glyde. He interrogates her then imprisons her in the House. Fosco’s spying is exposed, yet he persuades Glyde to release Laura.

Marian writes to the solicitor and to Mr Fairlie, trying to arrange a temporary refuge for Laura. She gives the letters to Fanny who has been dismissed and is returning to Limmeridge House.

Marian climbs out onto a verandah roof in the rain to overhear Glyde and Foco plotting to get money from Laura, and the search for Anne Catherick. Glyde assumes that Hartright and Laura know his ´secret´, which is also known by Anne Catherick and her mother.

Marian falls ill. Fosco confiscates and reads her diaries, even writing a mock-complimentary entry in them.

Fanny arrives at Limmeridge House with Marian´s letter. She has been intercepted and drugged by Countess Fosco. Count Fosco arrives to announce that Marian has a fever and to suggest that Fairlie should avoid a scandal by receiving Laura. Fairlie takes the line of least resistance and accepts.

The naive housekeeper Eliza Michelson gives an admiring view of Fosco, who plants an accomplice Mrs Rubelle in the sick room. Marian’s illness grows worse, and proves to be typhoid fever. When she recovers, the doctor is dismissed and Glyde sacks all the servants.

Mrs Michelson is sent away on a pointless errand to Torquay. On her return, Marian has been taken away by Fosco. Laura leaves Blackwater Park next day for London and Cumbria. Mrs Michelson discovers that Marian is still at Blackwater Park, and resigns her post. Mrs Rubelle leaves, and so does Glyde, in a great hurry.

Laura is taken to St John’s Wood in convulsions. She gets worse and appears to die of a diseased heart Walter Hartwright returns from abroad. He visits Laura’s grave, where he is met by Marian and Laura herself.

The Third Epoch

Count Fosco sends a letter to Marian announcing Laura’s death. Marian asks her solicitor to check, but he finds no suspicious circumstances. Count Fosco attends the funeral and writes that Anne Catherick has been recaptured and sent back to the Asylum.

Marian goes to the Asylum where the patient turns out to be Laura. Marian bribes a nurse to release her, and they go to Cumbria where her uncle refuses to recognise her [Fosco has kidnapped Laura, drugged her, and taken Laura to the Asylum as the recaptured Anne.]

Walter sets up in hiding with Marian and Laura. He begins to assemble evidence and accounts of events from participants (which constitute the text of the novel).

He consults the solicitor Kyle who warns him that he has no legal case. Walter is being followed by Glyde’s agents.

Walter tracks down Anne’s friend Mrs Clements, who relates that she took Anne to Grimsby for safety, but when Anne fell ill she wanted to communicate something to Laura. At Blackwater Park Mrs Clements meets Fosco who deceives her, prescribes drugs for Anne, and suggests their going to London. Once there, Fosco and his wife kidnap Anne.

Mrs Clements then relates the history of the Catherick family. Mrs Catherick refused to marry until she suddenly became pregnant by someone else. Percival Glyde came to live near them and began an intrigue with Mrs Catherick. When her husband discovered this, he beat Glyne, then emigrated. He pays his wife an allowance, which she does not touch, living instead off payments from Glyde.

Walter questions Mrs Catherick, who remains implacably opposed to answering any of his questions about Anne and Glyde. Walter assumes that Glyde is not Anne’s father.

Walter inspects the marriage records in an old vestry for evidence of Glyde’s parents’ marriage and finds a dubious entry. When he inspects a duplicate set of records he finds no entry. On his way back to the vestry he finds it on fire, with Glyde trapped inside. Walter organises a rescue, but it fails, and Glyde is killed.

Walter receives a letter from Mrs Catherick that reveals how Glyde forged the entry in the register of marriages. His parents were not married, and he needed a certificate in order to raise money on the estate. Mrs Catherick does not get on well with her daughter Anne, who learns that there is a secret but does not know its details. Nevertheless Glyde locks her up in an asylum with her mother’s consent.

Marian recounts meeting Fosco, who makes vague threats but reveals a vague sexual ‘interest’ in her. Consequently, Marian and Laura move house. Walter conjectures that Anne and Laura might have the same father.

Walter feels that to protect Laura from Fosco he must marry her. He wishes to establish her true identity against all the false evidence of her death. They get married.

Walter concludes from the existing evidence that Fosco must be a spy. He takes Pesca to identify Fosco at the opera – but Fosco is terrified by the sight of Pesca, who then reveals that he is a member of a secret revolutionary brotherhood.

Walter concludes that Fosco has a price on his head. He writes a letter to Pesca to be acted on if necessary the following morning, then goes to interview Fosco.

They challenge and threaten each other, but finally Walter gives Fosco a chance to escape in exchange for a written confession.

The confession relates how Fosco and Glyde arrived in England, both of them short of money. Fosco conceives the plan of extracting money out of Laura via her close resemblance to Anne.

His interest in ‘Chemistry’ is used to justify administering drugs to people, and he intercepts their mail. He kidnaps Anne, who dies in his house, then he conveys Laura under sedation to the asylum.

Walter gathers further documentary evidence, then Laura is taken back to Limmerage House where she is reinstated, despite the resistance of her uncle Fairlie. Walter organises a public statement of events, and then they return to London.

Walter receives a commission in Paris, where he learns about the assassination of Fosco. Walter and Laura have a child, who on the sudden death of his relative Frederick Fairlie inherits the Limmerage estate.

The Woman in White – principal characters

| Walter Hartright | a teacher of drawing (28) |

| Sarah Hartright | his sister |

| Professor Pesca | a dwarf teacher of Italian |

| Anne Catherick | the Woman in White |

| Marian Halcombe | shapely, poor, mannish |

| Laura Fairlie | rich, pretty, Marian’s half-sister |

| Frederick Fairlie | an aesthete and valetudinarian |

| Mrs Vesey | a vapid former governess to Laura |

| Percival Glyde | a fake and impoverished ‘Baronet’ |

| Vincent Gilmore | the Fairlie family solicitor |

| Mrs Clements | a friend to Anne Catherick |

| Mr Merriman | Glyde’s solicitor |

| Count Fosco | an Italian aesthete and spy |

| Countess Fosco | Fairlie’s sister, Laura’s aunt |

| Eliza Michelson | housekeeper at Blackwater Park |

| Mrs Rubelle | nurse employed by Fosco |

| Mr Kyle | solicitor in Gilmore’s office |

The Woman in White – further reading

William M. Clarke, The Secret Life of Wilkie Collins, London: Ivan R. Dee, 1988.

Tamar Heller, Dead Secrets: Wilkie Collins and the Female Gothic, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Winifred Hughes, The Maniac in the Cellar: Sensation Novels of the 1860s, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Sue Lonoff, Wilkie Collins and his Victorian Readers: A Study in the Rhetoric of Authorship, New York: AMS Press, 1982.

Catherine Peters, The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Walter C. Phillips, Dickens, Reade, and Collins: Sensation Novelists, New York: Library of Congress, 1919.

Lynn Pykett, Wilkie Collins: New Casebooks, London: Palgrave-Macmillan, 1998.

Nicholas Rance, Wilkie Collins and Other Sensation Novelists: Walking the Moral Hospital, London: Palgrave-Macmillan, 1991.

© Roy Johnson 2016

More on Wilkie Collins

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Chapter VIII. Grace visits Mrs Charmond in her gloomily placed house and makes a very good impression. Mrs Charmond invites her to be a traveling companion on her planned European tour. Meanwhile, Giles plants fir trees with Marty South.

Chapter VIII. Grace visits Mrs Charmond in her gloomily placed house and makes a very good impression. Mrs Charmond invites her to be a traveling companion on her planned European tour. Meanwhile, Giles plants fir trees with Marty South.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

To the Lighthouse

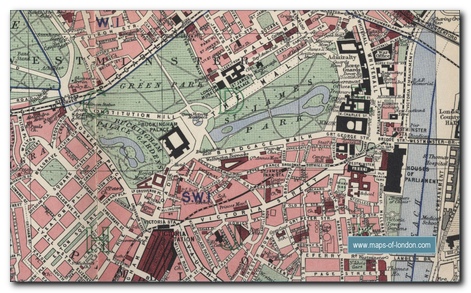

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures. his life and major writings

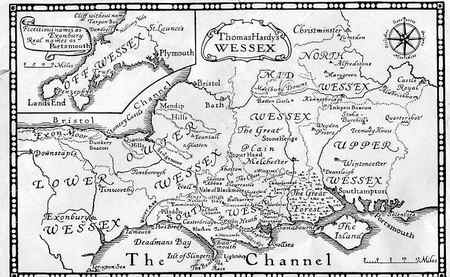

his life and major writings The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy

Under the Greenwood Tree

Under the Greenwood Tree Far from the Madding Crowd

Far from the Madding Crowd The Return of the Native

The Return of the Native The Mayor of Casterbridge

The Mayor of Casterbridge

Tess: DVD

Tess: DVD Jude the Obscure

Jude the Obscure The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy

Thomas Mann’s work spans the first half of the twentieth century. He started out writing in the tradition style of the nineteenth centry, but very quickly sought out themes and motifs which place him amongst modernists. His political views went through a similar transformation, from arch conservative before and during the first world war, to a very sceptical liberal democracy after the second. Many of his works are long and dense, and his style includes such typically Germanic features of writing in huge paragraphs, with lots of philosophic meditation embedded in his narratives. Beginners are best advised to sart with his earlier work – particularly novellas such as

Thomas Mann’s work spans the first half of the twentieth century. He started out writing in the tradition style of the nineteenth centry, but very quickly sought out themes and motifs which place him amongst modernists. His political views went through a similar transformation, from arch conservative before and during the first world war, to a very sceptical liberal democracy after the second. Many of his works are long and dense, and his style includes such typically Germanic features of writing in huge paragraphs, with lots of philosophic meditation embedded in his narratives. Beginners are best advised to sart with his earlier work – particularly novellas such as  Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family

Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family Death in Venice

Death in Venice Death in Venice – video film adaptation

Death in Venice – video film adaptation The Magic Mountain

The Magic Mountain Doktor Faustus

Doktor Faustus Mario and the Magician

Mario and the Magician