The letters of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson

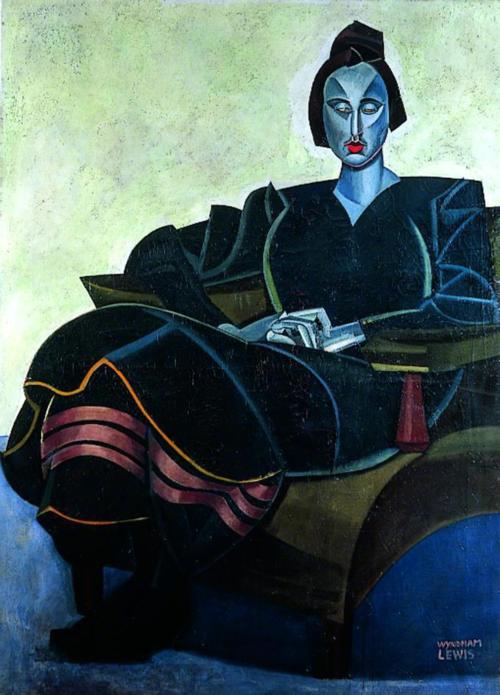

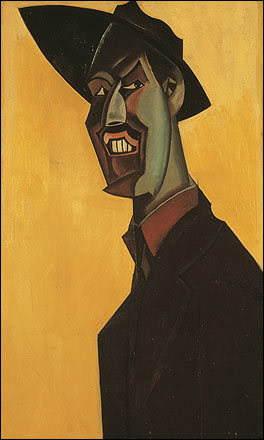

Harold Nicolson was a diplomat, a writer, and a politician, but he is best known for being married to Vita Sackville-West. They were both fringe members of the Bloomsbury Group. She too was a writer – indeed a best-selling author in the 1930s – but is best known as the woman who fell in love with and ran away with Virginia Woolf. Collectively, she and her husband are also best known for their rather unusual marriage and its arrangements which permitted them both to have lovers of the same sex whilst swearing their undying loyalty to each other. All this is recorded by their son in the equally famous account Portrait of a Marriage. Vita and Harold is a selection from their personal correspondence.

They wrote to each other voluminously (10,500 letters) throughout their long relationship – mainly because so much of it was spent apart. He worked in Persia whilst she stayed at home. Later, he had his rooms in Albany where he lived all week: she stayed in Sissinghurst writing and tending their gardens. The children were kept out of the way, and they met at weekends. In the meantime homosexual affairs flourished and they wrote to say how much they were missing each other.

They wrote to each other voluminously (10,500 letters) throughout their long relationship – mainly because so much of it was spent apart. He worked in Persia whilst she stayed at home. Later, he had his rooms in Albany where he lived all week: she stayed in Sissinghurst writing and tending their gardens. The children were kept out of the way, and they met at weekends. In the meantime homosexual affairs flourished and they wrote to say how much they were missing each other.

The early letters are very playful and, it has to be said, full of the protestations of a deep friendship based on shared interests and understanding on which they later claimed the success of their marriage was built.

She is very understanding when he contracts a venereal infection from another male guest at a weekend party he attended with her as his new wife. He is more concerned but ultimately forgiving when she leaves him and their two children to ‘elope’ with Violet Keppel, who had just married Denys Trefusis.

She even writes to him from the south of France whilst he is attending the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 – complaining that the exchange rate had dropped before she could convert her pounds sterling. He was negotiating the terms of the Armistice, whilst she was getting ready to gamble away her money in Monte Carlo.

It’s an interesting lesson in how letters must be put into a historical and cultural context in order to be properly understood. Vita writes a letter declaring undying love for her husband – but you would never guess it was written on the very day that she went off for the last time with Violet Trefusis.

Although Vita was the more successful author, his letters are more entertaining – at moments given to (unintentional?) humour:

[On horticulture] Shrubbery is a great problem if one is to avoid the suburban…[On his younger son] I said that about masturbation he must put it off as long as he possibly could – and that then he must only do it on Saturdays…[On education] I said that co-education was calculated to make boys homosexual for life, whereas Eton was only calculated to make them homosexual until 23 or 24.

Vita on the other hand is often more philosophically reflective, even if her observations are laced with a breathtaking notions of superiority:

The whole system of marriage is wrong. It ought, at least, to be optional and no stigma attached if you prefer a less claustrophobic form of contact. For it is claustrophobic. It is only very, very intelligent people like us who are able to rise superior; and I have a suspicion, my darling, that even our intelligence…wouldn’t have sufficed if our temperamental weaknesses didn’t happen to dovetail as well as they do…In fact our common determination for personal liberty: to have it ourselves, and to allow it to each other.

Serene detachment and au-dessus de la mêlée – yet this is the woman who travelled all the way to Paris to seduce Violet Trefusis whilst she was on her honeymoon, and forebad her to have any sexual relationship with her new husband Denys.

It’s amazing how many important political events Harold was connected with. He was the only person to be present at the settlement of both world wars. And he knew just about everyone who was anyone. In the course of his busy life he hobnobs with James Joyce, Somerset Maugham, Winston Churchill, the Duke of Windsor, and Charles de Gaulle.

No doubt there are today people with unconventional marriages, bisexual relations, connections in high places, and lots of money – but this one offers a glimpse of a world which has gone by. And I somehow doubt that people in future will be reading the emails and text messages which have replaced the written letter as a means of communication.

© Roy Johnson 2001

Nigel Nicolson (ed), Vita & Harold: The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson 1910-1962, London: Phoenix, 1993, pp.452, ISBN: 1857990617

More on Harold Nicolson

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on Vita Sackville-West

More on the novella

More on literary studies

Vita (Victoria Mary) Sackville-West (1892-1962) was a prolific poet and novelist – though she is probably best known for her writing on gardens and her affair with

Vita (Victoria Mary) Sackville-West (1892-1962) was a prolific poet and novelist – though she is probably best known for her writing on gardens and her affair with

1899. Vladimir Nabokov was born in St Petersburg on April 23 [the same birthday as Shakespeare]. His father was a prominent jurist, liberal politician, and a member of the Duma (Russia’s first parliament). His mother was the daughter of a wealthy aristocratic family.

1899. Vladimir Nabokov was born in St Petersburg on April 23 [the same birthday as Shakespeare]. His father was a prominent jurist, liberal politician, and a member of the Duma (Russia’s first parliament). His mother was the daughter of a wealthy aristocratic family.