his life, writings, and adventures

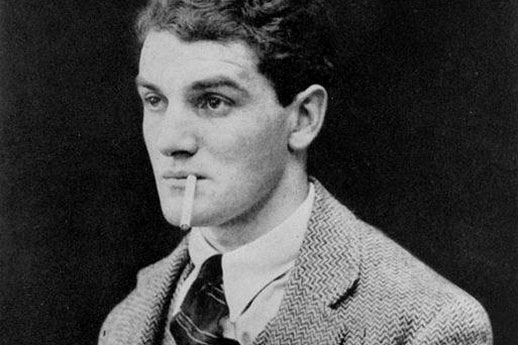

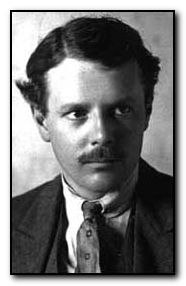

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987) was born in Malta, the son of an English army officer. After spending some of his childhood in South Africa and India, he grew up in an isolated Cotswold village. He studied at Radley College and then the military academy at Sandhurst. Travel and adventure were to be his way of life, and at sixteen he ran away from home. His aim was to reach Central Asia but the outbreak of the Balkan War and shortage of money caused him to return to England. He studied to enter the Indian Police (as did his near-contemporary George Orwell) but on the outbreak of the First World War, he joined the army. He spent over two years on the Western Front, reaching the rank of captain and winning a Military Cross and a Croix de Guerre.

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987) was born in Malta, the son of an English army officer. After spending some of his childhood in South Africa and India, he grew up in an isolated Cotswold village. He studied at Radley College and then the military academy at Sandhurst. Travel and adventure were to be his way of life, and at sixteen he ran away from home. His aim was to reach Central Asia but the outbreak of the Balkan War and shortage of money caused him to return to England. He studied to enter the Indian Police (as did his near-contemporary George Orwell) but on the outbreak of the First World War, he joined the army. He spent over two years on the Western Front, reaching the rank of captain and winning a Military Cross and a Croix de Guerre.

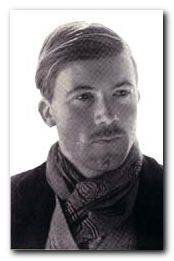

Following the end of the war, his fellow officer and friend Ralph Partridge introduced him to the fabled Bloomsbury Group. It was through Partridge that Brenan met Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, and Virginia Woolf. As soon as he was released from military service he packed a rucksack and left England aboard a ship bound for Spain. He was disillusioned with the way of life in England and with the stifling social and sexual hypocrisies of British bourgeois society. He rebelled against becoming part of it and, being a romantic and adventurer, resolved to seek a more breathable atmosphere in which to live.

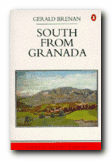

He also wanted to educate himself and become a writer. As he records in his best known travel memoir, South from Granada, he felt ashamed that his public school upbringing had left him with a very poor education. He shipped 2,000 books out to his chosen destination – an area deep in Andalucia known as ‘La Alpujarra’.

South from Granada is a classic in which Brenan describes setting up home in a remote Spanish village in the 1920s. He has a marvellous grasp of geography; he captures the rugged atmosphere of the region; and he has a particularly detailed knowledge of botany. Local characters and customs are vividly recounted. Bloomsbury enthusiasts will be delighted his by hilarious accounts of visits made by Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf under very difficult conditions, as well as a meeting with Roger Fry in Almeria.

South from Granada is a classic in which Brenan describes setting up home in a remote Spanish village in the 1920s. He has a marvellous grasp of geography; he captures the rugged atmosphere of the region; and he has a particularly detailed knowledge of botany. Local characters and customs are vividly recounted. Bloomsbury enthusiasts will be delighted his by hilarious accounts of visits made by Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf under very difficult conditions, as well as a meeting with Roger Fry in Almeria.

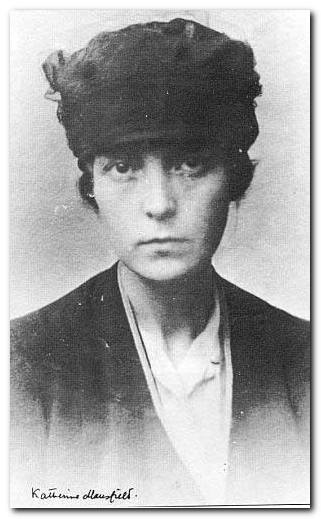

Ralph Partridge and Dora Carrington, recently married, also visited him with Lytton Strachey in 1920, and Carrington’s fondness for Brenan is thought to have started on this trip. She carried on an extensive correspondence with Brenan for the next several years and in 1922 they had a brief affair, which was rapidly discovered by Partridge. There was a year of silence between the three, before reconciliation took place and the often-stormy friendship continued for the remainder of their lives.

In 1930 he married the American poetess Gamel Woolsey. In 1934 the Brenans left Spain and were unable to return until 1953, partly because of the Spanish civil war. During the Second World War he was an Air Raid Warden and a Home Guard. They spent this time in Aldbourne and Brenan expressed his feelings of exile from Spain by completing three major works on Spanish life and literature. On his return to Spain he began a series of autobiographical works, including South from Granada, A Life of One’s Own, and A Personal Record.

The Spanish Labyrinth has become the classic account of the background to the Spanish Civil War. It has all the vividness of Brenan’s personal experiences and intelligent insights. He tries to see the issues in Spanish politics objectively, whilst bearing witness to the deep involvement which is the only possible source of much of this richly detailed account. As a literary figure on the fringe of the Bloomsbury Group, Gerald Brenan lends to this narrative an engaging personal style that has become familiar to many thousands of readers over the decades since it was first published

The Spanish Labyrinth has become the classic account of the background to the Spanish Civil War. It has all the vividness of Brenan’s personal experiences and intelligent insights. He tries to see the issues in Spanish politics objectively, whilst bearing witness to the deep involvement which is the only possible source of much of this richly detailed account. As a literary figure on the fringe of the Bloomsbury Group, Gerald Brenan lends to this narrative an engaging personal style that has become familiar to many thousands of readers over the decades since it was first published

After the death of his wife in 1968, a young English student of the poetry of the Spanish saint – St. John of the Cross – joined Gerald as his secretary and companion. This young lady Lynda Jane Nicholson Price remained with him for 14 years. In the later part of his life he was confined to an old people’s home in Aldermaston, but a group of his Spanish friends ‘kidnapped’ him and took him back to what they regarded as his spiritual home, just outside Malaga. He died on January 19, 1987 while in the hands of the Spanish Medical Services who had undertaken to care for him. He was acclaimed for his services to Spanish literature, buried in Malaga, and a plaque dedicated to his work was fixed to the house where he had lived in Yegen. It reads:

“In this house for a period of seven years [1920-1934] lived the British Hispanist GERALD BRENAN, who universalised the name of Yegen and the customs and traditions of La Alpujarra. The Town Hall, grateful, dedicates this plaque.” YEGEN, 3 JANUARY, 1982

Bloomsbury Group – web links

![]() Hogarth Press first editions

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, featuring designs by Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and others.

![]() The Omega Workshops

The Omega Workshops

A brief history of Roger Fry’s experimental Omega Workshops, which had a lasting influence on interior design in post First World War Britain.

![]() The Bloomsbury Group and War

The Bloomsbury Group and War

An essay on the largely pacifist and internationalist stance taken by Bloomsbury Group members towards the First World War.

![]() Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Tate Gallery Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury

Mini web site featuring photos, paintings, a timeline, sub-sections on the Omega Workshops, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant, and biographical notes.

![]() Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Bloomsbury: Books, Art and Design

Exhibition of paintings, designs, and ceramics at Toronto University featuring Hogarth Press, Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Quentin Bell, and Stephen Tomlin.

![]() Blogging Woolf

Blogging Woolf

A rich enthusiast site featuring news of events, exhibitions, new book reviews, relevant links, study resources, and anything related to Bloomsbury and Virginia Woolf

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf

Search the texts of all Woolf’s major works, and track down phrases, quotes, and even individual words in their original context.

![]() A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

A Mrs Dalloway Walk in London

An annotated description of Clarissa Dalloway’s walk from Westminster to Regent’s Park, with historical updates and a bibliography.

![]() Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Women’s History Walk in Bloomsbury

Annotated tour of literary and political homes in Bloomsbury, including Gordon Square, University College, Bedford Square, Doughty Street, and Tavistock Square.

![]() Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain

News of events, regular bulletins, study materials, publications, and related links. Largely the work of Virginia Woolf specialist Stuart N. Clarke.

![]() BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

BBC Audio Essay – A Eulogy to Words

A charming sound recording of a BBC radio talk broadcast in 1937 – accompanied by a slideshow of photographs of Virginia Woolf.

![]() A Family Photograph Albumn

A Family Photograph Albumn

Leslie Stephens’ collection of family photographs which became known as the Mausoleum Book, collected at Smith College – Massachusetts.

![]() Bloomsbury at Duke University

Bloomsbury at Duke University

A collection of book jacket covers, Fry’s Twelve Woodcuts, Strachey’s ‘Elizabeth and Essex’.

© Roy Johnson 2000-2014

More on Gerald Brenan

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) was born into an upper middle-class family in Tehran, where his father (Lord Carnock) was the British ambassador to Persia. as it then was. He was educated at Wellington College then Balliol College Oxford, where he graduated with a third-class degree. He entered the diplomatic service in 1908 and was posted to Constantinople where he became a specialist in Balkan affairs. In 1910 he met

Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) was born into an upper middle-class family in Tehran, where his father (Lord Carnock) was the British ambassador to Persia. as it then was. He was educated at Wellington College then Balliol College Oxford, where he graduated with a third-class degree. He entered the diplomatic service in 1908 and was posted to Constantinople where he became a specialist in Balkan affairs. In 1910 he met

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando

Orlando Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

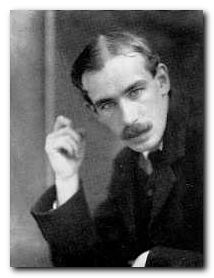

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures. Maynard Keynes was born and raised in Cambridge, the seat of intellectual and political power, even more so then than now. He was also educated at Eaton – and yet his social origins were quite modest. One grandfather John Brown was an apprentice printer from Lancashire who later graduated from Owens College (Manchester University) and went on to become a preacher. The other grandfather made his fortune from cultivating dahlias and roses. His father John Neville Keynes went to University College London and then to Cambridge where he briefly became a lecturer and where he met Keynes’ mother, who was a student at Newnham Hall. However, Neville (the family used their middle names) did not feel suited to the life of a don, and became instead an administrator in the examinations board.

Maynard Keynes was born and raised in Cambridge, the seat of intellectual and political power, even more so then than now. He was also educated at Eaton – and yet his social origins were quite modest. One grandfather John Brown was an apprentice printer from Lancashire who later graduated from Owens College (Manchester University) and went on to become a preacher. The other grandfather made his fortune from cultivating dahlias and roses. His father John Neville Keynes went to University College London and then to Cambridge where he briefly became a lecturer and where he met Keynes’ mother, who was a student at Newnham Hall. However, Neville (the family used their middle names) did not feel suited to the life of a don, and became instead an administrator in the examinations board. At this point Keynes’s personal life became quite complex, with cross-connections that have since made the Bloomsbury Group famous. He was a friend and ex-lover of Lytton Strachey, who had fallen in love with his own cousin

At this point Keynes’s personal life became quite complex, with cross-connections that have since made the Bloomsbury Group famous. He was a friend and ex-lover of Lytton Strachey, who had fallen in love with his own cousin  However, this mixing with Bloomsbury also brought him personal distress. Duncan Grant started an affair with

However, this mixing with Bloomsbury also brought him personal distress. Duncan Grant started an affair with  In the early 1920s Keynes was actively involved in solving the lingering problem of post-war reparations, something in which he participated as an economist, a government advisor, and (secretly) as an unofficial diplomatist. At the same time he formed a group to take over the liberal journal Nation and Athenaeum of which he made Leonard Woolf the editor. Then, in the midst of all this, he surprised everyone by falling in love with the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, who stayed in England when Diaghilev de-camped to Monte Carlo.

In the early 1920s Keynes was actively involved in solving the lingering problem of post-war reparations, something in which he participated as an economist, a government advisor, and (secretly) as an unofficial diplomatist. At the same time he formed a group to take over the liberal journal Nation and Athenaeum of which he made Leonard Woolf the editor. Then, in the midst of all this, he surprised everyone by falling in love with the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, who stayed in England when Diaghilev de-camped to Monte Carlo. John Maynard Keynes (pronounced “Kaynz”) was one the most important figures in the history of economics. He revolutionized the subject with his classic study, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). This is generally regarded as one of the most influential social science treatises of the twentieth century. It quickly and permanently changed the way the world looked at the economy and the role of government in society. He was born in 1883 in Cambridge into an academic family. His father, John Nevile Keynes, was a lecturer at the University of Cambridge teaching logic and political economy. His mother Florence Ada Brown was a remarkable woman who was a highly successful author and a pioneer in social reform. She was also the first woman mayor of Cambridge. An interesting family detail is that although Keynes lived to the age of sixty-three, both his parents outlived him.

John Maynard Keynes (pronounced “Kaynz”) was one the most important figures in the history of economics. He revolutionized the subject with his classic study, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). This is generally regarded as one of the most influential social science treatises of the twentieth century. It quickly and permanently changed the way the world looked at the economy and the role of government in society. He was born in 1883 in Cambridge into an academic family. His father, John Nevile Keynes, was a lecturer at the University of Cambridge teaching logic and political economy. His mother Florence Ada Brown was a remarkable woman who was a highly successful author and a pioneer in social reform. She was also the first woman mayor of Cambridge. An interesting family detail is that although Keynes lived to the age of sixty-three, both his parents outlived him.