tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

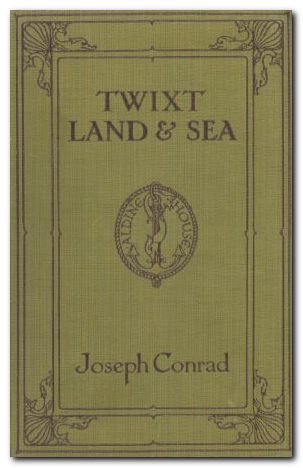

Freya of the Seven Isles was written in late 1910–early 1911. It was first published in Metropolitan Magazine in early 1912 and in London Magazine for July 1912. It was then collected in ’Twixt Land and Sea, published by J.M.Dent & Sons in 1912. The other tales in the collection were A Smile of Fortune and The Secret Sharer.

Paul Gaugin 1848-1903

Freya of the Seven Isles – critical commentary

Narrative

Conrad is rightly celebrated as a writer who creates highly wrought narratives with complex time schemes, which are often constructed to produce amazing feats of ironic and tragic drama. The complexity is often created by having both an inner and an outer narrator as sources of information about events and characters, or by having the information assembled in an order which does not follow the actual chronology of events. This can sometimes make extra intellectual demands on the reader – but at their best they carry with them compensating artistic effects of a high order. It is no accident that Conrad (along with his contemporary and friend Henry James) is seen as one of the precursors of the Modernist movement.

However, it has to be said that these complexities of narrative technique are not always kept under control: see comments on Nostromo (1904) and Under Western Eyes (1911) for instance. Conrad sometimes seems to forget who is telling the story, and first person narratives often drift to become an account of events in third person omniscient mode.

In the case of Freya of the Seven Isles there is a breakdown in the logic of the narrative which results in people giving an account of events they have not witnessed or cannot know about. The sequence or chain of knowledge is as follows:

- The outer narrator receives a letter written to him by someone in the Mesman office in Macassar. The letter mentions Nielsen, which prompts the narrator’s reminiscence.

- His reminiscence becomes the principal narrative, and the narrator is a participant in events. He is acquainted with Nielsen and Freya.

- The tale gradually turns into a narrative in third person omniscient mode. That is, it includes the thoughts and feelings of the characters in the tale.

- When the outer narrator tows Jasper Allen out to sea in Part II, he draws attention to the fact that it is the last time he ever sees Jasper, Nielsen, Freya, and Heemskirk together.

- This point is reinforced in Part III, when the narrator points out that it is the last time he ever sees Jasper. Yet he knows what Jasper’s secret plans are, later in the tale.

- At the end of Part III the narrator goes back to London, yet from Part IV onwards, the third person omniscient narrative continues. There are scenes, thoughts, fears, and feelings which cannot have been transmitted to the narrator – for a number of reasons:

- there is nobody else in the scene to relay the information

- the subject is missing ((Jasper, Heemskirk)

- the subject is dead (Freya)

- Late in the tale, Conrad seems to remember that information about events was prompted by the letter. The narrator observes ‘All this story, read in my friend’s very chatty letter.’ But the information in the letter could only be related to events as seen in Macassar. His friend could not possibly know about Freya’s thoughts and fears when being secretly spied upon by Heemskirk. (for instance).

- Nielsen visits the narrator in London to reveal the news of Freya’s death – but he too cannot know about the thoughts and feelings of characters in scenes in which he was not present.

What you make of these weaknesses will depend upon your levels of tolerance, but it is worth pointing to them if only because Conrad seems to go out of his way to make his narrative logic and credibility more complex than it needs to be. All of these events could have been conveyed in traditional third person omniscient narrative mode

Freya of the Seven Isles – study resources

![]() Freya of the Seven Isles – CreateSpace editions – Amazon UK

Freya of the Seven Isles – CreateSpace editions – Amazon UK

![]() Freya of the Seven Isles – CreateSpace editions – Amazon US

Freya of the Seven Isles – CreateSpace editions – Amazon US

![]() Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle eBook

Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle eBook

![]() Freya of the Seven Isles – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

Freya of the Seven Isles – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

![]() Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

Freya of the Seven Isles – plot summary

Part I. The un-named narrator gives an account of Nielsen, a Dane who is an experienced seaman in the Eastern Malayan Archipelago. He is frightened of both the Dutch and the Spanish authorities, and has settled on a remote island. Following the death of his wife, their beautiful daughter Freya goes to live with him on the island.

She is courted by Jasper Allen, the owner of Bonito, a fast and elegant brig, who feels that the narrator might be a rival for Freya. Nielsen is more worried about the authorities than Jasper’s courtship of his daughter. Jasper puts lots of effort into maintaining the brig, regarding it as a potential home for Freya, who he hopes to marry.

Part II. Nielsen’s hospitality is abused by Heemskirk, the commander of a gunboat, who is also interested in Freya. The narrator counsels Freya to keep Jasper as quiet as possible. She wishes to become mistress of the elegant brig Bonito.

Part III. A few weeks later the narrator meets Jasper in Singapore. Jasper and Freya are planning to elope, but she wants him to delay until she is twenty-one, which leaves them eleven months left to wait. Jasper has taken on a dubious mate Schultz, who is given to drink and stealing.

The narrator visits Nielsen shortly before Freya’s birthday, immediately following visits from Jasper and Heemskirk, who has been particularly obnoxious. The visit also seems to have upset Freya. The narrator leaves on the eve of the planned elopement, then has to return to England. He writes to both Jasper and Freya but hears nothing in return.

Part IV. The narrative goes back to Heemskirk’s visit. He annoys Nielsen and provokes his sense of insecurity, especially regarding Freya. He sneaks up, trying to spy on Freya and Jasper. Freya feels she must try to protect both Jasper and her father. Jasper wants to take her away there and then; but she advises caution and waiting. They all have dinner together, then Jasper leaves for his ship accompanied by Nielsen. In their absence a drunken Heemskirk menaces and molests Freya, who ends up smacking his face very hard. When Nielsen returns he naively thinks that Heemskirk has toothache. Neilsen urges Freya not to upset a man who has political influence in the region. In the morning Heemskirk spies on Freya who is watching Jasper’s brig departing – then he slinks off.

Part V. Heemskirk makes some unspecified political arrangements with the ‘authorities’, then steams out in his gunboat to intercept Jasper in the Bonito. He accuses him of illegal trading, and takes over the brig, towing it towards Macassar. But he deliberately wrecks the brig on a reef at high tide.

Part VI. The Bonita’s stock of arms has disappeared – which arouses suspicions of illegal arms trading by Jasper. It emerges that the arms were stolen and sold by Schultz, but when he makes his confession to the authorities they refuse to believe him. He ends up cutting his own throat. The brig meanwhile is looted whilst it is stranded on the reef.

Time passes, and the outer narrator is in London when he is visited by Nielsen, who fills in the rest of the tale.

After getting news of the wreck of the Bonito, Freya becomes ill, then tells her father everything about the elopement plan. Nielsen goes to see Jasper, who is in terminal despair. Nielsen sells up and takes Freya to live in Hong Kong. She reproaches herself for not being more courageous and dies of pneumonia.

Joseph Conrad – video biography

Freya of the Seven Isles – main characters

| I | the un-named narrator |

| Nielsen | a Danish widower |

| Freya | his attractive daughter |

| Jasper Allen | English owner of the fast brig Bonito |

| Heemskirk | Dutch commander of the gunboat Neptun |

| Schultz | a drunken and kleptomaniac mate |

First edition – J.M.Dent & Sons 1912

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Joseph Conrad’s writing table

Further reading

![]() Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

![]() Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

![]() Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

![]() Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

![]() Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

![]() John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

![]() Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

![]() Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

![]() Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

![]() Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

![]() Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

![]() Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

![]() Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

![]() Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

![]() George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

![]() John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

![]() James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

![]() Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

![]() Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

![]() J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

![]() John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

![]() Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

![]() Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

![]() Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Other writing by Joseph Conrad

Lord Jim (1900) is the earliest of Conrad’s big and serious novels, and it explores one of his favourite subjects – cowardice and moral redemption. Jim is a ship’s captain who in youthful ignorance commits the worst offence – abandoning his ship. He spends the remainder of his adult life in shameful obscurity in the South Seas, trying to re-build his confidence and his character. What makes the novel fascinating is not only the tragic but redemptive outcome, but the manner in which it is told. The narrator Marlowe recounts the events in a time scheme which shifts between past and present in an amazingly complex manner. This is one of the features which makes Conrad (born in the nineteenth century) considered one of the fathers of twentieth century modernism.

Lord Jim (1900) is the earliest of Conrad’s big and serious novels, and it explores one of his favourite subjects – cowardice and moral redemption. Jim is a ship’s captain who in youthful ignorance commits the worst offence – abandoning his ship. He spends the remainder of his adult life in shameful obscurity in the South Seas, trying to re-build his confidence and his character. What makes the novel fascinating is not only the tragic but redemptive outcome, but the manner in which it is told. The narrator Marlowe recounts the events in a time scheme which shifts between past and present in an amazingly complex manner. This is one of the features which makes Conrad (born in the nineteenth century) considered one of the fathers of twentieth century modernism.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of the process of Imperialism. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement, and it is based on his own experiences as a sea captain. This volume also contains ‘An Outpost of Progress’ – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’.

Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of the process of Imperialism. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement, and it is based on his own experiences as a sea captain. This volume also contains ‘An Outpost of Progress’ – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2013

Joseph Conrad web links

Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Biography, tutorials, book reviews, study guides, videos, web links.

Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Brief notes introducing his major works in recommended editions.

Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary career, style, politics, and further reading.

Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production notes, box office, trivia, and quizzes.

Works by Joseph Conrad

Large online database of free HTML texts, digital scans, and eText versions of novels, stories, and occasional writings.

The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

Conradian journal, reviews. and scholarly resources.

The Joseph Conrad Society of America

American-based – recent publications, journal, awards, conferences.

Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Locate a word or phrase – in the context of the novel or story.

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

Joseph Conrad complete tales

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

George Orwell (real name, Eric Blair) is renowned as a master of plain English prose style. He went out of his way to make himself understood to as many people as possible. He wrote in a very political era – the 1930s and 1940s. It’s hardly surprising that much of his work is written in support of democratic causes and as a warning against any form of totalitarianism, whether from the left or right. He started as a novelist of lower middle-class misery in the tradition of George Gissing, found a new strength in his reportages from working life and the Spanish Civil War, and ended his short life with two rather un-English books which have become classics of the political novel. he was not a great writer of the first rank, but a very decent man with a gift for clear expression and a desire to tell the truth and expose the fake. Martin Seymour Smith sums him up admirably by saying “he was a master of lucidity, of saying what he meant, of exposing the falsity of what he called double-think”

George Orwell (real name, Eric Blair) is renowned as a master of plain English prose style. He went out of his way to make himself understood to as many people as possible. He wrote in a very political era – the 1930s and 1940s. It’s hardly surprising that much of his work is written in support of democratic causes and as a warning against any form of totalitarianism, whether from the left or right. He started as a novelist of lower middle-class misery in the tradition of George Gissing, found a new strength in his reportages from working life and the Spanish Civil War, and ended his short life with two rather un-English books which have become classics of the political novel. he was not a great writer of the first rank, but a very decent man with a gift for clear expression and a desire to tell the truth and expose the fake. Martin Seymour Smith sums him up admirably by saying “he was a master of lucidity, of saying what he meant, of exposing the falsity of what he called double-think”

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

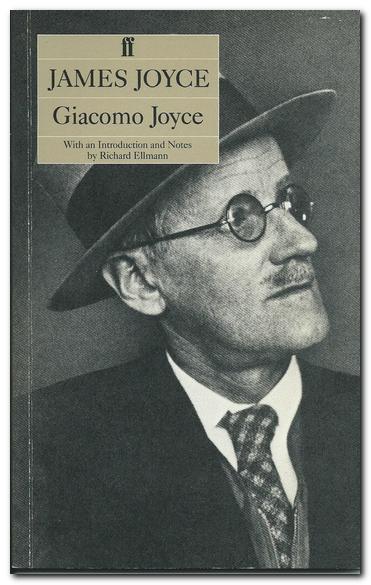

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

During Christmas dinner, whilst Pip is scared that someone will notice the missing pie. Police officers arrive and hunt through the marshes outside the village for escaped convicts. They accost the man helped by Pip, but when questioned about where he got the food and file, he claims he stole the items himself. The police take him off to the Hulk, a giant prison ship.

During Christmas dinner, whilst Pip is scared that someone will notice the missing pie. Police officers arrive and hunt through the marshes outside the village for escaped convicts. They accost the man helped by Pip, but when questioned about where he got the food and file, he claims he stole the items himself. The police take him off to the Hulk, a giant prison ship.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory. Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.