tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

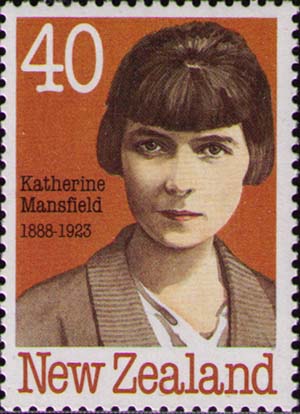

Marriage a la Mode was one of a group of six stories commissioned from Katherine Mansfield by Clement Shorter, the editor of the Sphere, a fashionable illustrated newspaper targeted at British citizens living in the colonies. The story was written in August 1921 and published in December the same year. It was later reprinted in The Garden Party and Other Stories published in 1922.

Marriage a la Mode – critical commentary

Anthony Alpers, Katherine Mansfield’s biographer, describes Marriage a la Mode as a ‘shallow … bill-paying’ story whose lack of depth and subtlety is a result of her badly needing money to pay doctors’ fees during her illness whilst living in Montana-sur-Sierre in Switzerland.

It is certainly true that the story requires very little close reading or interpretive skill to yield its single meaning. William is a crushed husband figure whose tender feelings for his family are completely trampled upon by his wife’s selfishness, her social climbing, and her self-indulgent bohemianism. He is more or less excluded socially from his own home by her empty-headed friends. When he is driven by necessity to communicate his love for her by letter, she responds by reading it out for the amusement and mockery of her house guests. When she realises what a heartless and vulgar thing she has done, there is a momentary impulse to reach out to her husband in response – but instead she chooses to rejoin her friends.

It is a sceptical, if not jaundiced view of marriage, but it is to Mansfield’s credit that as a writer who so often reveals masculine foibles and insensitivities in her work, she creates here a sympathetic account of a working man and a scathing portrayal of his selfish and empty-headed wife.

Plagiarism?

A number of commentators have pointed to the similarities between Marriage a la Mode and a story by Anton Checkhov called Not Wanted (1886). In fact the most severe of these critics have accused her of direct plagiarism.

In Checkhov’s story a Court official Pavel Zaikin is travelling out to his summer cottage by train in the summer heat. He complains to a fellow traveller in ‘ginger trousers’ about the cost and inconvenience, which he attributes to ‘women’s frivolity’.

He finds his son alone in the cottage: his wife is attending the rehearsal of a play and has not prepared any dinner. Zaikin feels anger gnawing at him and in bad temper he scolds his son without reason – then regrets having done so.

His wife Nadyezhda returns from the rehearsal with her friend Olga and two men. She sends the servant out for ‘sardines, vodka, and cheese’. The thespians then begin noisy rehearsals until late, after which she invites the two men to stay the night. She also moves Zaikin out of his own bed to accommodate Olga. In the early morning Zaikin gets dressed and goes out into the street, where he meets the man in ginger trousers again. He too has a houseful of unexpected visitors.

The similarities in the two stories are the working husband who is abused by a self-indulgent wife; the train journey; the houseful of disruptive bohemians; and the fact that the man is treated like an outsider in his own home.

But this was not the first time Katherine Mansfield had re-told a story by Checkhov. Her early piece The-Child-Who-Was-Tired is taken from Checkhov’s Sleepyhead (1888) and her plagiarism was the subject of a debate on her conscious or unconscious borrowings in the pages of theTimes Literary Supplement in the 1950s.

However, she composed so many original and outstanding stories of entirely her own invention, that it is unlikely these accusations will cause the damage to her reputation some people hope for and others fear. But there is one telling detail in Marriage a la Mode that nails the story inescapably to its Russian origins – and that is the choice of sardines for the improvised evening meal. Isabel’s arty friends consume sardines and whisky, whilst Checkhov’s amateur theatricals have their sardines and vodka. There is simply no escaping the fact that this detail is copied. Fish and vodka are entirely native to Russian culture, but would be exceptional in English social life.

Marriage a la Mode – study resources

![]() Katherine Mansfield’s Collected Works

Katherine Mansfield’s Collected Works

Three published collections of stories – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Collected Short Stories of Katherine Mansfield

The Collected Short Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Wordsworth Classics paperback edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield

The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Penguin Classics paperback edition – Amazon UK

![]() Katherine Mansfield Megapack

Katherine Mansfield Megapack

The complete stories and poems in Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() Katherine Mansfield’s Collected Works

Katherine Mansfield’s Collected Works

Three published collections of stories – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() The Collected Short Stories of Katherine Mansfield

The Collected Short Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Wordsworth Classics paperback edition – Amazon US

![]() The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield

The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Penguin Classics paperback edition – Amazon US

![]() Katherine Mansfield Megapack

Katherine Mansfield Megapack

The complete stories and poems in Kindle edition – Amazon US

Marriage a la Mode – plot summary

A London solicitor William is returning home on Saturday afternoon to his fashionable and demanding wife Isabel. He feels anxious about not having bought presents for his two sons, but buys them a melon and pineapple instead. He reads through legal papers, but is distracted by thoughts of his wife, who has cooled in her feelings towards him. They have moved from a modest to a much bigger house, and Isabel has made new friends, but William thinks back to their earlier days when he was happier.

Isabel is waiting for him at the station, but she is accompanied by some party-loving friends. She appropriates the fruit, and they buy sweets for the boys instead, meanwhile making asinine comments. When they arrive at the house, the party go off swimming, leaving William to reflect critically on the way the house is being run. Returning from the swim, they eat sardines and drink whisky, disattending to William.

The following day William is preparing to return to London. He has not seen his sons and has had no opportunity to talk to Isabel. When he gets to his train he decides to write to her instead.

The next day Isabel and her friends are lazing about in the sun when William’s letter arrives. It is a long love letter in which he reveals his feelings for her, and says he doesn’t want to stand between her and her happiness. She reads it out aloud to her friends, who scoff and make fun of the letter. Isabel suddenly feels ashamed of what she has done, and has the impulse to write a reply, but when the friends invite her to go swimming, she leaves with them instead.

Katherine Mansfield – web links

Katherine Mansfield at Mantex

Life and works, biography, a close reading, and critical essays

Katherine Mansfield at Wikipedia

Biography, legacy, works, biographies, films and adaptations

Katherine Mansfield at Online Books

Collections of her short stories available at a variety of online sources

Not Under Forty

A charming collection of literary essays by Willa Cather, which includes a discussion of Katherine Mansfield.

Katherine Mansfield at Gutenberg

Free downloadable versions of her stories in a variety of digital formats

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, including Mansfield’s ‘Prelude’

Katherine Mansfield’s Modernist Aesthetic

An academic essay by Annie Pfeifer at Yale University’s Modernism Lab

The Katherine Mansfield Society

Newsletter, events, essay prize, resources, yearbook

Katherine Mansfield Birthplace

Biography, birthplace, links to essays, exhibitions

Katherine Mansfield Website

New biography, relationships, photographs, uncollected stories

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Katherine Mansfield

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on short stories

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Studying Fiction

Studying Fiction

Jacob’s Room

Jacob’s Room

The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors