advice on writing academic essays – from start to finish

David Pirie’s sub-title here is ‘a guide for students of literature’ – but his advice will be useful for anybody in the arts or humanities. What he offers is to talk you through the process, from understanding the question to producing and submitting the final draft. He adopts a very sensible approach, and the advice he offers is timeless. The essay as an academic exercise has endured because it is both a form of intellectual self-discovery and a flexible yet taxing means of assessment. He starts with analysing and understanding questions, then organising the ‘research’ for your answer – including detailed advice on taking notes. All this quickly becomes an introduction to literary criticism.

His chapter on devising a suitable structure for an essay explores the standard approaches to this task. These are discussing the arguments for and against a proposition; following the chronological order of events; and constructing a logical sequence of topics. I think a few more concrete examples would have been helpful here. The chapter on how to make a detailed case is more useful, precisely because he examines a series of concrete examples, showing how to quote and examine selected passages. The same is true of his chapter on style, where he illustrates his warnings against repetition, vagueness, generalisation, plagiarism, and overstatement.

His chapter on devising a suitable structure for an essay explores the standard approaches to this task. These are discussing the arguments for and against a proposition; following the chronological order of events; and constructing a logical sequence of topics. I think a few more concrete examples would have been helpful here. The chapter on how to make a detailed case is more useful, precisely because he examines a series of concrete examples, showing how to quote and examine selected passages. The same is true of his chapter on style, where he illustrates his warnings against repetition, vagueness, generalisation, plagiarism, and overstatement.

There’s something eloquent yet curiously old-fashioned about his prose style. The voice is like an audio recording of someone speaking to us from an earlier age. And he uses phrases which flatter his readers. He talks about students ‘writing criticism’ – as if their coursework exercises were about to be published.

It’s a shame there is no bibliography or index. These are omissions which should be rectified if the book ever makes its long-overdue second edition.

© Roy Johnson 2005

David Pirie, How to Write Critical Essays: a guide for students of literature, London: Routledge, 1985, pp.139, ISBN: 0415045339

More on study skills

More on writing skills

More on online learning

The Longest Journey

The Longest Journey A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

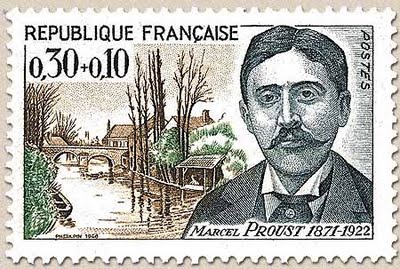

The Cambridge Companion to Proust

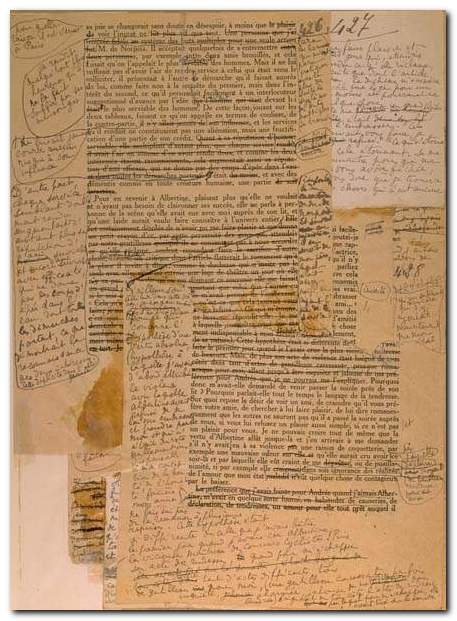

The Cambridge Companion to Proust Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller