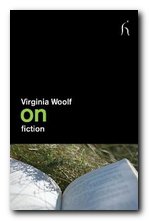

essays on novelists, fiction, and the novel

Virginia Woolf on Fiction is a collection of essays on the subject of imaginative narratives. Virginia Woolf never went to university – in fact she hardly even went to school in the sense we think of formal education today. Yet she had a superb education – largely via free access to her father’s library in which he encouraged her to browse. From this she gained not only a first-hand acquaintance with the literary classics, but a love of books and an appreciation of the sheer pleasure of reading. She also studied languages – including Latin and Greek.

She went on to become a pivotal figure in the development of the modernist novel, and her collected non-fiction essays now stand at six large volumes. In fact she published her first writing as book reviews in the Manchester Guardian and the Times Literary Supplement. She also cultivated the discursive essay as a literary form, and this collection testifies to both the wide range of her erudition and her sharp insights into the nature of fiction as a practising novelist.

She went on to become a pivotal figure in the development of the modernist novel, and her collected non-fiction essays now stand at six large volumes. In fact she published her first writing as book reviews in the Manchester Guardian and the Times Literary Supplement. She also cultivated the discursive essay as a literary form, and this collection testifies to both the wide range of her erudition and her sharp insights into the nature of fiction as a practising novelist.

The first essay ‘Hours in a Library’ (Times Literary Supplement, 1916) deals with the pleasures of reading and the distinctions to be made between classical and contemporary writers. Not surprisingly, her sympathies lie largely with the traditional – for good reasons:

it is oddly difficult in the case of new books to know which are the real books and what it is they are telling us, and which are the stuffed books which will come to pieces when they have lain about for a year or two

In ‘The Narrow Bridge of Art’ (New York Herald Tribune, 1927) she challenges the critic (and herself) to do just the opposite – that is, to look at contemporary writing and hazard a guess about cultural trends and the possible literary future. She does this by explaining why poetry can no longer deal successfully with the huge contradictions which the first world war and its aftermath had made so apparent. The same is also true of the poetic drama – which by that time had become a completely dead literary genre. But prose fiction in the elastic form of the novel has a better chance.

What she goes on to do is sketch out a menu of options for the novel in terms of form and content. The novel of the future will be poetic, but written in prose. It will uncover new truths about life – by exploring those aspects of human existence which writers have so far ignored:

the power of music, the stimulus of sight, the effect upon us of the shape of trees or the play of colour…the delight of movement, the intoxication of wine

Her argument is almost a working compilation of notes for what was to be her next major experimental novel The Waves which she published only four years later.

Another essay, Women and Fiction (The Forum, 1929) is a rehearsal of the arguments she went on to expand in ‘A Room of One’s Own’ – reflections on the relationship between women and literature. Woolf emphasises that this means both literature written by women and the role of women in literature – two elements that she argues are closely interlinked.

She explores the reasons why the female writer did not produce fiction until the nineteenth century – largely because she had no independence, no income of her own, and no ‘room to herself’. But given the advantages of post-suffrage woman in the twentieth century, Woolf sees the possibility of female writers discovering their own voices. All the now-familiar issues of écriture feminine are sketched out here in their earliest form:

before a woman can write exactly as she wishes to write, she has many difficulties to face … the very form of the sentence does not fit her. It is a sentence made by men; it is too loose, too heavy, too pompous for a woman’s use.

The centrepiece of the collection is ‘Phases of Fiction’ (The Bookman, 1929). In this she looks at the essential nature of the novel, and what it is that makes readers voluntarily suspend disbelief to immerse themselves in invented worlds and imaginary characters. She divides novelists into realists (Maupassant) romantics (Stevenson) creators of character (Dickens) and psychologists (Proust). Her conclusion is that the novel as a literary genre, for all its weaknesses and comparative recency, offered readers at its best a deep experience of “the growth and development of feelings”.

We watch the character and behaviour of Becky Sharp or Richard Feverel and instinctively come to an opinion about them as about real people, tacitly accepting this or that impression, judging each motive, and forming an opinion that they are charming but insincere, good or dull, secretive but interesting, as we make up our minds about the characters of the people we meet.

She stands foursquare in defence of the novelist’s art and the relevance of fiction to a civilized intellectual life – and yet in one of her many insightful asides she accurately predicts what has happened to the novel in the time since her writing.

Hence the futility at present of any theory of ‘the future of fiction’. The next ten years will certainly upset it; the next century will blow it to the winds.

This publication deserves a proper introduction, situating the essays in their original contexts, but as an example of Woolf’s supple and intelligent non-fiction writing it offers insights into the nature of fiction which are timeless.

© Roy Johnson 2011

Virginia Woolf, On Fiction, London: Hesperus Press, 2011, pp.94, ISBN: 1843916185

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf is collection of essays which addresses the full range of her intellectual perspectives – literary, artistic, philosophical and political. It provides new readings of all nine novels and fresh insight into Woolf’s letters, diaries and essays. The progress of Woolf’s thinking is revealed from Bloomsbury aestheticism through her hatred of censorship, corruption and hierarchy to her concern with all aspects of modernism. This book explores the immense range of social and political issues behind her search for new forms of narrative.

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf is collection of essays which addresses the full range of her intellectual perspectives – literary, artistic, philosophical and political. It provides new readings of all nine novels and fresh insight into Woolf’s letters, diaries and essays. The progress of Woolf’s thinking is revealed from Bloomsbury aestheticism through her hatred of censorship, corruption and hierarchy to her concern with all aspects of modernism. This book explores the immense range of social and political issues behind her search for new forms of narrative.  Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject. Ideal for beginners.

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject. Ideal for beginners.

Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens