tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

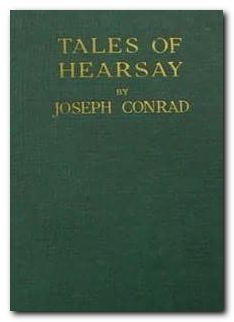

The Tale was written 1916 and first published 1917 in The Strand Magazine. It was posthumously collected in Tales of Hearsay, published by T. Fisher Unwin in 1925. The other tales in the volume were The Warrior’s Soul, Prince Roman. and The Black Mate. This is the only story Conrad wrote about the first world war.

The Tale – critical commentary

Narrative

As was common in tales he was writing at this time, Conrad blends two narrative modes in one story here. The tale begins in third person omniscient narrative mode, with events related largely from the commander’s point of view. When asked to recount a story by the woman, his dramatisation of the incident of the two ships (although related by him in first person narrative mode) is cast as a third person narrative. He refers to the commander of the warship as ‘he’ – though it is fairly clear from the outset that he is talking about himself. Conrad’s tinkering with narrative modes is perfectly justified here – because the commander is giving an account of something he has himself experienced

The moral

Without a specialist knowledge of the rules of maritime engagement during a period of war, it’s hard to know what the commander’s other options were. Conrad is surely expecting his readers to be sympathetic to the commander, and yet his action of sending the crew of the other ship to their more-or-less certain death would be inexcusable, even if they were supplying the enemy with materials. The commander was in a position to seize the other vessel – though it could be argued that in times of war, subtle distinctions are frequently ignored or ‘lost’.

The Tale – study resources

![]() Tales of Hearsay – CreateSpace editions – Amazon UK

Tales of Hearsay – CreateSpace editions – Amazon UK

![]() Tales of Hearsay – CreateSpace editions – Amazon US

Tales of Hearsay – CreateSpace editions – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle eBook

The Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle eBook

![]() The Tale – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

The Tale – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

![]() Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

The Tale – plot summary

A naval officer, on leave from the First World War, tells a woman a story at her request. It’s of an English naval commander who claims that the war at sea is not as distinct and definite as the war on land. Whilst on patrol somewhere in the North Sea his ship spots some wreckage late at night. It’s thought this could be some neutral country supplying replenishments to enemy submarines. The commander’s ship is then engulfed by fog, so they pull into a nearby cove, where they discover another ship. It is from a neutral country and has had engine trouble. However, the commander is suspicious, and decides to board the ship himself, to inspect.

The captain of the neutral ship is a ‘Northman’ who claims he has been becalmed by fog and his engines have failed, but have now been repaired. His story is plausible, and it tallies with the ship’s log book. He claims the cargo is being taken to a British port. Everything he says corresponds with what can be seen, and yet something in his manner makes the English commander doubt him.

The commander is suspicious because the other ship did not make itself known, and had the power to sail away. The other ship’s captain (who appears to have been drinking) claims that he does not know where he is. The commander increasingly feels he is being confronted by a huge lie, and yet he has no proof of anything amiss. The captain pleads that he is only engaged on the journey because he owns the ship and needs the money.

The English commander orders the Northman to take his ship out of the cove, and gives him false directions which take him onto rocks, where the ship sinks, with the loss of all on board. The commander – who has been talking about himself – does not know if he has condemned innocent or guilty men to death

Joseph Conrad – video biography

The Tale – principal characters

| — | an English naval commander |

| — | the woman he is comforting |

| — | the ‘Northman’ |

first edition, Fisher Unwin 1925

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Joseph Conrad’s writing table

Further reading

![]() Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

![]() Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New Yoprk: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

![]() Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

![]() Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

![]() Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

![]() John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

![]() Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

![]() Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

![]() Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

![]() Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

![]() Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

![]() Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

![]() Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

![]() Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

![]() George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

![]() John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

![]() James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

![]() Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

![]() Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

![]() J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

![]() John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

![]() Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

![]() Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

![]() Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Other writing by Joseph Conrad

Lord Jim (1900) is the earliest of Conrad’s big and serious novels, and it explores one of his favourite subjects – cowardice and moral redemption. Jim is a ship’s captain who in youthful ignorance commits the worst offence – abandoning his ship. He spends the remainder of his adult life in shameful obscurity in the South Seas, trying to re-build his confidence and his character. What makes the novel fascinating is not only the tragic but redemptive outcome, but the manner in which it is told. The narrator Marlowe recounts the events in a time scheme which shifts between past and present in an amazingly complex manner. This is one of the features which makes Conrad (born in the nineteenth century) considered one of the fathers of twentieth century modernism.

Lord Jim (1900) is the earliest of Conrad’s big and serious novels, and it explores one of his favourite subjects – cowardice and moral redemption. Jim is a ship’s captain who in youthful ignorance commits the worst offence – abandoning his ship. He spends the remainder of his adult life in shameful obscurity in the South Seas, trying to re-build his confidence and his character. What makes the novel fascinating is not only the tragic but redemptive outcome, but the manner in which it is told. The narrator Marlowe recounts the events in a time scheme which shifts between past and present in an amazingly complex manner. This is one of the features which makes Conrad (born in the nineteenth century) considered one of the fathers of twentieth century modernism.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of the process of Imperialism. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement, and it is based on his own experiences as a sea captain. This volume also contains ‘An Outpost of Progress’ – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’.

Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of the process of Imperialism. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement, and it is based on his own experiences as a sea captain. This volume also contains ‘An Outpost of Progress’ – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2013

Joseph Conrad web links

Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Biography, tutorials, book reviews, study guides, videos, web links.

Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Brief notes introducing his major works in recommended editions.

Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary career, style, politics, and further reading.

Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production notes, box office, trivia, and quizzes.

Works by Joseph Conrad

Large online database of free HTML texts, digital scans, and eText versions of novels, stories, and occasional writings.

The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

Conradian journal, reviews. and scholarly resources.

The Joseph Conrad Society of America

American-based – recent publications, journal, awards, conferences.

Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Locate a word or phrase – in the context of the novel or story.

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

Joseph Conrad complete tales

The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

From his earliest years he produced book reviews, essays, lectures, film reviews, prologues, and translations in addition to his now-famous fictions. He even invented literary genres – the essay which is part philosophic reflection and part fiction; studies of imaginary works; and biographies of people who did not exist. This in addition to spoofs, mind games, and metaphysical writings of a kind that seem to transcend national boundaries – which is partly why he managed to establish his international reputation.

From his earliest years he produced book reviews, essays, lectures, film reviews, prologues, and translations in addition to his now-famous fictions. He even invented literary genres – the essay which is part philosophic reflection and part fiction; studies of imaginary works; and biographies of people who did not exist. This in addition to spoofs, mind games, and metaphysical writings of a kind that seem to transcend national boundaries – which is partly why he managed to establish his international reputation.

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton