conjugal life a la Bloomsbury

Nigel Nicolson is the son of writer Vita Sackville-West and diplomat-politician Harold Nicolson. When his parents died he found a locked leather Gladstone bag in his mother’s study, cut it open, and discovered a diary containing an autobiographical account of her affair with Violet Trefusis. Portrait of a Marriage is made up of these diary entries, interspersed with his own explanations of what went on in those parts of the story his mother doesn’t cover.

It’s not really a portrait of a marriage at all until the final chapter. Harold Nicolson remains a vaporous non-presence throughout, and there is almost nothing about the relationship between them except for her protestations at ‘depending’ on him. The central issue is her passionate three-year fling that has her dressing up as a man, leaving her husband and children behind to ‘elope’ to France, and to live in Monte Carlo, gambling at the tables with money they didn’t have, whilst Trefusis was debating the wisdom of marrying her fiancé Denys, whom she didn’t love or desire.

It’s not really a portrait of a marriage at all until the final chapter. Harold Nicolson remains a vaporous non-presence throughout, and there is almost nothing about the relationship between them except for her protestations at ‘depending’ on him. The central issue is her passionate three-year fling that has her dressing up as a man, leaving her husband and children behind to ‘elope’ to France, and to live in Monte Carlo, gambling at the tables with money they didn’t have, whilst Trefusis was debating the wisdom of marrying her fiancé Denys, whom she didn’t love or desire.

It’s an amazing story, and most instructive in class terms. Husbands colluding with their wives’ lovers for the sake of money to keep estates solvent, whilst paternity suits raged to the tune of £40,000 (this in the 1900s).

I was also very struck by how much of Sackville-West’s literary style is similar to Virginia Woolf’s. She is a great fan of the stream of immediate memory, and a narrative couched in extended metaphors and rhapsodic interludes. There are lots of schooners breasting silvery waves with the wind full in their sails, and that sort of thing.

There’s nothing here that will be remotely shocking in the sexual sense to modern readers. ‘I had her’ is about as explicit as it gets. But the behaviour – duplicitous, self-seeking, naive, and hypocritical – is breathtaking. Vita Sackville West finally broke off the relationship with Trefusis because she thought she might have had some sexual connection with Denys Trefusis – the man she had recently married – whilst West had two children with Harold Nicolson. Actually, Violet Trefusis hadn’t had any such connection, having made it a condition of her marriage contract.

There’s a lot of utterly snobbish ancestor-worship to get through and Nicolson’s chapters are written in a creakingly old-fashioned manner: ‘She permitted him liberties but not licence’. In fact Nicolson fils seems as wrapped up in snobbery as his mother:

her real friends were souls, but real souls who had some breeding and a gun, who could make a fourth at bridge, and who knew the difference between claret and burgundy

I found it quite hard to keep my rage down when reading of the almost unbelievable concern for money, status, and class. The events are only just over a hundred years ago, and this account of them was written in the 1970s, but it was like reading about social dinosaurs.

The latter part of the book outlines West’s affairs with Geoffrey Scott and Virginia Woolf – both of which she recounted in detail to her husband. Their son makes the case that the bond between them was strong enough to outlast these affairs – which it did, though on the basis that they had no sexual relationship with each other.

Of course you don’t need a brass plaque on your door to realise why a child would want to portray his bisexual and adulterous parents in the best possible light, but I must say all this is sometimes difficult to accept calmly.

As time went on the affairs petered out and the Nicolsons settled down to a quieter life, the major part of which they spent separately – he in London, she in their house at Sissinghurst – which might account for the longevity of the union.

These were people who seemed to have separated out sex from marriage, who obviously cared for each other, and yet spent most of their time apart, writing endless letters saying how much they missed each other. They also made sure their children were kept out of the way at all times. Maybe there’s a lesson in there somewhere?

However, there is one very good thing to say for this memoir-cum-history. Anyone who wants a vivid, living example of the social values and the bohemian behaviour of the Bloomsbury Group need look no further. It’s all here.

© Roy Johnson 2004

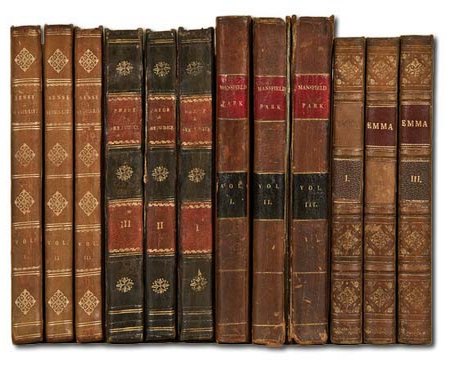

Nigel Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, London: Orion Books, 2004, pp.216, ISBN: 1857990609

More on Harold Nicolson

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

More on Vita Sackville-West

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.