his life, writings, and cultural context

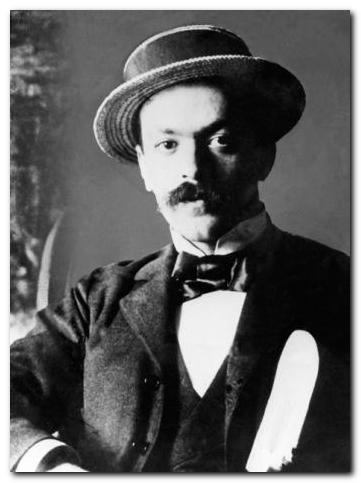

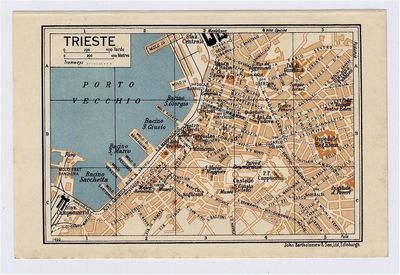

Italo Svevo was the pen name of the Austro-Italian writer Aron Ettore Schmitz. He was born in 1861 in Trieste, which at that time was part of the Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian empire – and remained so until the end of the first world war. His mother was Italian, and his father a German Jewish businessman. He was educated with his brothers at a commercial school in Wurzburg, Germany, where he became fluent in the language. Italian was actually his second language, the first being the Triestine dialect which was used at home.

After two further years of business studies in Trieste, he was forced to abandon his studies when his father’s glassware business went bankrupt. He took up employment as a correspondence clerk in the Viennese Union Bank, where he stayed for the next twenty years. During this time he produced his first novel, Una vita (A Life) (1893). Like all his other books, it was published at his own expense.

Following the death of his parents he married his cousin Livia Veneziano, the daughter of a wealthy Italian who manufactured specialised industrial paints used on warships. In 1897 he became a partner in his father-in-law’s business and was quite successful in commercial activities, making profitable excursions to France and Germany, and setting up a branch of the company in England.

In 1898 he published his second novel Senilità (As a Man Grows Older). Both of these novels were largely ignored at the time, but in 1907 Svevo was enrolled at the Berlitz School of Languages to learn English, where his tutor was a twenty-five year old James Joyce, who had taken up exile in Trieste. Joyce read the novels and championed Svevo’s work. The two men became great friends.

However, Svevo was discouraged by his lack of literary success, and appears to have given up writing completely around that time. He devoted the next twenty-five years to his work as a representative for the family paint business in which, despite his cultural and intellectual interests, he was successfully enterprising. He lived for some time in the borough of Greenwich in south London, documenting the differences he encountered in Edwardian English culture in a series of letters he wrote to his wife: This England is So Different: Italo Svevo’s London Writings.

In 1925 when Svevo published La Conscienza di Zeno (Confessions of Zeno), Joyce arranged for the work to be translated into French and published in Paris. The work was critically acclaimed and marked his first major success. He entered into a second phase of creativity and produced a number of stories, a novella, and an unfinished novel. He spent the last years of his life lecturing on his own work and writing Further Confessions of Zeno, which was never completed. In 1928 he was involved in a motoring accident in Trieste and he died a few days later from his injuries.

Italo Svevo – principal works

![]() 1893 – Una vita (A Life)

1893 – Una vita (A Life)

![]() 1898 – Senilità (As a Man Grows Older

1898 – Senilità (As a Man Grows Older

![]() 1925 – La conscienza di Zeno (Confessions of Zeno)

1925 – La conscienza di Zeno (Confessions of Zeno)

![]() 1926 – La novella del buon vecchio e della bella fanciulla

1926 – La novella del buon vecchio e della bella fanciulla

![]() 1926 – Una burla riuscita (A Perfect Hoax)

1926 – Una burla riuscita (A Perfect Hoax)

![]() 1927 – La madre (The Mother)

1927 – La madre (The Mother)

Italo Svevo – study resources

![]() A Life – Secker & Warburg- Amazon UK

A Life – Secker & Warburg- Amazon UK

![]() A Life – Secker & Warburg – Amazon US

A Life – Secker & Warburg – Amazon US

![]() As A Man Grows Older – NYRB Classics – Amazon UK

As A Man Grows Older – NYRB Classics – Amazon UK

![]() As A Man Grows Older – NYRB Classics – Amazon US

As A Man Grows Older – NYRB Classics – Amazon US

![]() Confessions of Zeno – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

Confessions of Zeno – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Confessions of Zeno – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

Confessions of Zeno – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() Italo Svevo: A Double Life – Clarendon Press – Amazon UK

Italo Svevo: A Double Life – Clarendon Press – Amazon UK

![]() Italo Svevo: A Double Life – Clarendon Press – Amazon US

Italo Svevo: A Double Life – Clarendon Press – Amazon US

![]() Svevo’s London Writings – Troubador Press – Amazon UK

Svevo’s London Writings – Troubador Press – Amazon UK

![]() Svevo’s London Writings – Troubador Press – Amazon US

Svevo’s London Writings – Troubador Press – Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2016

More on Italo Svevo

More on biography

More on literary studies

More on the arts

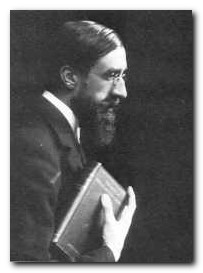

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

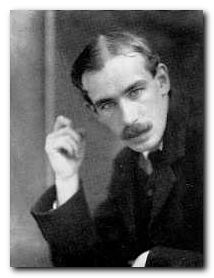

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures. Maynard Keynes was born and raised in Cambridge, the seat of intellectual and political power, even more so then than now. He was also educated at Eaton – and yet his social origins were quite modest. One grandfather John Brown was an apprentice printer from Lancashire who later graduated from Owens College (Manchester University) and went on to become a preacher. The other grandfather made his fortune from cultivating dahlias and roses. His father John Neville Keynes went to University College London and then to Cambridge where he briefly became a lecturer and where he met Keynes’ mother, who was a student at Newnham Hall. However, Neville (the family used their middle names) did not feel suited to the life of a don, and became instead an administrator in the examinations board.

Maynard Keynes was born and raised in Cambridge, the seat of intellectual and political power, even more so then than now. He was also educated at Eaton – and yet his social origins were quite modest. One grandfather John Brown was an apprentice printer from Lancashire who later graduated from Owens College (Manchester University) and went on to become a preacher. The other grandfather made his fortune from cultivating dahlias and roses. His father John Neville Keynes went to University College London and then to Cambridge where he briefly became a lecturer and where he met Keynes’ mother, who was a student at Newnham Hall. However, Neville (the family used their middle names) did not feel suited to the life of a don, and became instead an administrator in the examinations board. At this point Keynes’s personal life became quite complex, with cross-connections that have since made the Bloomsbury Group famous. He was a friend and ex-lover of Lytton Strachey, who had fallen in love with his own cousin

At this point Keynes’s personal life became quite complex, with cross-connections that have since made the Bloomsbury Group famous. He was a friend and ex-lover of Lytton Strachey, who had fallen in love with his own cousin  However, this mixing with Bloomsbury also brought him personal distress. Duncan Grant started an affair with

However, this mixing with Bloomsbury also brought him personal distress. Duncan Grant started an affair with  In the early 1920s Keynes was actively involved in solving the lingering problem of post-war reparations, something in which he participated as an economist, a government advisor, and (secretly) as an unofficial diplomatist. At the same time he formed a group to take over the liberal journal Nation and Athenaeum of which he made Leonard Woolf the editor. Then, in the midst of all this, he surprised everyone by falling in love with the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, who stayed in England when Diaghilev de-camped to Monte Carlo.

In the early 1920s Keynes was actively involved in solving the lingering problem of post-war reparations, something in which he participated as an economist, a government advisor, and (secretly) as an unofficial diplomatist. At the same time he formed a group to take over the liberal journal Nation and Athenaeum of which he made Leonard Woolf the editor. Then, in the midst of all this, he surprised everyone by falling in love with the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, who stayed in England when Diaghilev de-camped to Monte Carlo. John Maynard Keynes (pronounced “Kaynz”) was one the most important figures in the history of economics. He revolutionized the subject with his classic study, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). This is generally regarded as one of the most influential social science treatises of the twentieth century. It quickly and permanently changed the way the world looked at the economy and the role of government in society. He was born in 1883 in Cambridge into an academic family. His father, John Nevile Keynes, was a lecturer at the University of Cambridge teaching logic and political economy. His mother Florence Ada Brown was a remarkable woman who was a highly successful author and a pioneer in social reform. She was also the first woman mayor of Cambridge. An interesting family detail is that although Keynes lived to the age of sixty-three, both his parents outlived him.

John Maynard Keynes (pronounced “Kaynz”) was one the most important figures in the history of economics. He revolutionized the subject with his classic study, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). This is generally regarded as one of the most influential social science treatises of the twentieth century. It quickly and permanently changed the way the world looked at the economy and the role of government in society. He was born in 1883 in Cambridge into an academic family. His father, John Nevile Keynes, was a lecturer at the University of Cambridge teaching logic and political economy. His mother Florence Ada Brown was a remarkable woman who was a highly successful author and a pioneer in social reform. She was also the first woman mayor of Cambridge. An interesting family detail is that although Keynes lived to the age of sixty-three, both his parents outlived him.