revolution and capital accumulation in Latin America

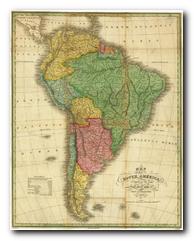

Nostromo is generally regarded by most Conrad commentators as his greatest novel. It embraces wide ranging themes of political struggle, international capitalism, the expansion of Europe and the United States into Latin America, various forms of personal heroism and sacrifice, and the dreams and obsessions which can lead people to self-destruction. The location of the novel is Costaguana, a fictional country on the western seaboard of South America, and the focus of events is in its capital Sulaco, where a silver mine has been inherited by English-born Charles Gould but is controlled by American capitalists in San Francisco.

Competing military factions plunge the country in a state of civil war, and Gould tries desperately to keep the mine working. Amidst political chaos, he dispatches a huge consignment of silver, putting it into the hands of the eponymous hero, the incorruptible Capataz de Cargadores, Nostromo. However, things do not go according to plan. It is almost impossible to provide an account of the plot without giving away what are called in movie criticism ‘plot spoilers’. But the silver does not reach its intended destination, and the remainder of the novel is concerned with both the civil conflict and the attitudes of the people who know that the silver exists, and their vainglorious attempts to acquire it.

Competing military factions plunge the country in a state of civil war, and Gould tries desperately to keep the mine working. Amidst political chaos, he dispatches a huge consignment of silver, putting it into the hands of the eponymous hero, the incorruptible Capataz de Cargadores, Nostromo. However, things do not go according to plan. It is almost impossible to provide an account of the plot without giving away what are called in movie criticism ‘plot spoilers’. But the silver does not reach its intended destination, and the remainder of the novel is concerned with both the civil conflict and the attitudes of the people who know that the silver exists, and their vainglorious attempts to acquire it.

The novel has a curious but on the whole impressive structure. The first part of the book is an extraordinarily slow-moving – almost static – account of Costaguana and the back-history of the main characters in the story. Then the central section – more than half the novel – is taken up with the dramatic events of just two or three days and nights in which rebel forces attack the town, the silver is smuggled out, and the scene is set for disaster.

This central section of the novel which covers the scenes of military insurgency and high drama conveys very convincingly the uncertainty of civil war, the powerlessness of individuals, and the force of large scale events. Bandits suddenly become generals, all normal communications are cut off, and nobody can be sure where to turn to for law and order. Amazingly, around two hundred pages of narrative cover only two or three days of action – much of it at night.

The main point of Conrad’s story is that the silver of the mine corrupts almost all who come into contact with it. The inheritance and running of the mine estrange Charles Gould from his wife; once Nostromo has concealed the silver, his knowledge of its location eventually corrupts him; and the rebel leader Sotillo is driven almost made with desire to possess it. Only the saintly Emilia Gould has the strength to resist it, refusing to know where it is buried, even when the information is offered by the last person to know, on his death bed.

A great deal of the narrative tension in this long novel turns on who knows what about whom, and many of the key scenes are drenched in dramatic irony built on coincidences which have all the improbability of the nineteenth century novel hanging about them. At one point a completely new character suddenly appears as a stowaway on a boat, and then improbably survives a collision with another ship in the dark by hanging onto the other boat’s anchor. And this is merely a plot device allowing him to transmit misleading information to his captors – and incidentally allows Conrad to indulge in a rather unpleasant bout of anti-Semitism.

In common with many other novels from Conrad’s late phase, the narrative is conveyed to us in a very complex manner. It passes from third person omniscient narrator to first person accounts of events by fictional characters. Authorial point of view and the chronology of events both change alarmingly; the narrative is sometimes taken over temporarily by a fictional character, or is recounted via an improbably long letter which we are meant to believe is being written (in pencil) in the heat of gunfire and other tumultuous events.

There’s also a great deal of geographic uncertainty. As reports come in from one end of the country to the other, and the loyalty of one province and its leaders is mentioned in relation to another – as well as its strategic position on the seaboard – I began to wish for a map to conceptualise events.

Once a heroic solution has been found for the plight of the beleaguered loyalists (an epic Paul Revere type ride on horseback by Nostromo) the story suddenly flashes forward to the successful years of recovery and the aftermath. Nostromo seeks to consolidate his successful position by a judicious marriage, but is distracted by his passionate love for his intended’s younger sister. Even this detail is linked to the silver of the mine, and it brings about the truly tragic finale.

Despite all Conrad’s stylistic peculiarities (and even some lapses in grammar) this is a magnificent novel which amply repays the undoubtedly demanding efforts required to read it. But that is true of many modern classics – from Mrs Dalloway to Ulysses and Remembrance of Things Past.

© Roy Johnson 2009

Joseph Conrad, Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp.524, ISBN: 0199555915

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

More on Joseph Conrad tales

The location of the novel is Costaguana, a fictional country on the western seaboard of South America, and the focus of events is in its capital Sulaco, where a silver mine has been inherited by English-born Charles Gould but is controlled by American capitalists in San Francisco. Competing military factions plunge the country in a state of civil war, and Gould tries desperately to keep the mine working. Amidst political chaos, he dispatches a huge consignment of silver, putting it into the hands of the eponymous hero, the incorruptible Capataz de Cargadores, Nostromo.

The location of the novel is Costaguana, a fictional country on the western seaboard of South America, and the focus of events is in its capital Sulaco, where a silver mine has been inherited by English-born Charles Gould but is controlled by American capitalists in San Francisco. Competing military factions plunge the country in a state of civil war, and Gould tries desperately to keep the mine working. Amidst political chaos, he dispatches a huge consignment of silver, putting it into the hands of the eponymous hero, the incorruptible Capataz de Cargadores, Nostromo. A great deal of the narrative tension in this long novel turns on who knows what about whom, and many of the key scenes are drenched in dramatic irony built on coincidences which have all the improbability of the nineteenth century novel hanging about them. At one point a completely new character suddenly appears as a stowaway on a boat, and then improbably survives a collision with another ship in the dark by hanging onto the other boat’s anchor. And this is merely a plot device allowing him to transmit misleading information to his captors – and incidentally allows Conrad to indulge in a rather unpleasant bout of anti-semitism.

A great deal of the narrative tension in this long novel turns on who knows what about whom, and many of the key scenes are drenched in dramatic irony built on coincidences which have all the improbability of the nineteenth century novel hanging about them. At one point a completely new character suddenly appears as a stowaway on a boat, and then improbably survives a collision with another ship in the dark by hanging onto the other boat’s anchor. And this is merely a plot device allowing him to transmit misleading information to his captors – and incidentally allows Conrad to indulge in a rather unpleasant bout of anti-semitism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended. The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes

Far from the Madding Crowd

Far from the Madding Crowd The Return of the Native

The Return of the Native The Mayor of Casterbridge

The Mayor of Casterbridge

Following Sasha’s return to Russia, the desolate, lonely Orlando returns to writing The Oak Tree, a poem started and abandoned in his youth. This period of contemplating love and life leads him to appreciate the value of his ancestral stately home, which he proceeds to furnish lavishly and then plays host to the populace. Ennui sets in and a persistent suitor’s harassment leads to Orlando’s appointment by King Charles II as British ambassador to Constantinople. Orlando performs his duties well, until a night of civil unrest and murderous riots. He falls asleep for a lengthy period, resisting all efforts to rouse him.

Following Sasha’s return to Russia, the desolate, lonely Orlando returns to writing The Oak Tree, a poem started and abandoned in his youth. This period of contemplating love and life leads him to appreciate the value of his ancestral stately home, which he proceeds to furnish lavishly and then plays host to the populace. Ennui sets in and a persistent suitor’s harassment leads to Orlando’s appointment by King Charles II as British ambassador to Constantinople. Orlando performs his duties well, until a night of civil unrest and murderous riots. He falls asleep for a lengthy period, resisting all efforts to rouse him.

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens. Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller