handbook, explanation, plot summary, and characters

After nearly 100 years, Marcel Proust’s The Remembrance of Things Past remains as formidable a reading task as when it first appeared. Indeed, possibly more so – since it was originally published in single volumes at intervals, which gave contemporary readers a chance to digest its contents slowly. But it now exists in seven volumes totalling 3,200 pages, a million and a half words, and containing more than 400 characters.

This is not an intellectual journey to be undertaken lightly, and even experienced readers need all the help they can get to deal with a literary construction of this magnitude. Patrick Alexander’s guide is an attempt to provide all the assistance that’s required. The book is in three parts. The first offers an overview then a summary of what takes place in each of the seven volumes of the novel. Part two is a who’s who – thumbnail sketches of the principal characters, what they do, and to whom they are related.

This is not an intellectual journey to be undertaken lightly, and even experienced readers need all the help they can get to deal with a literary construction of this magnitude. Patrick Alexander’s guide is an attempt to provide all the assistance that’s required. The book is in three parts. The first offers an overview then a summary of what takes place in each of the seven volumes of the novel. Part two is a who’s who – thumbnail sketches of the principal characters, what they do, and to whom they are related.

Part three offers a brief account of Proust’s life, notes on Paris and the Belle Epoque, and brief essays on French history and the notorious Dreyfus affair in particular.

During the course of his paraphrase, Alexander examines the ‘epiphanies’ for which Proust is famous; he shows the links between characters and events spanning the whole of the seven volumes which will not be apparent to a first-time reader; and he looks at Proust’s techniques of detailed and protracted analysis which, to anyone who has paid close enough attention, are not simply analyses but highly imaginative and extended metaphors which demonstrate his intellectual skill for seeing similarities between apparently disparate objects.

As Alexander points out, Proust’s novel is also an amazing cultural encyclopedia. Whilst the narrative explores issues of love, friendship, jealousy, memory and time, it is also packed with cultural references:

His literary references range from Xenophon to (then) contemporary novelists such as Zola; his musical references cover western music from Palestrina to Puccini, and he refers to more than one hundred individual painters from Botticelli to the avant garde Léon Bakst. All of these references are used to express and illustrate startlingly original insights into every aspect of the human condition, from love and sex to religion and death – and all with a freshness and comic sense of the absurd.

It is often observed by those who have read Proust that so powerful are the evocations of place and the recreation of his life experiences, that readers afterwards find it difficult to believe that they are not their own. “Yes – That’s exactly how it is!” sums up this sort of reaction, though of course it is his genius to have put it into words in the first place.

And for a writer so renowned for prolixity (even longeurs) what is not so frequently observed is the fact that he is much given to placing pithy aphorisms in his text, deeply embedded in huge paragraphs though they might often be.

This book should appeal to the intelligent ‘Common Reader’ who wants to undertake the extended literary journey that a reading of Proust presents. And it will be a reliable guide mainly because it was written by exactly such a person, composed as a homage to a writer he had come to love.

© Roy Johnson 2009

Patrick Alexander, Marcel Proust’s Search for Lost Time: A Reader’s Guide to The Remembrance of Things Past, New York: Vintage, 2009, pp.3391, ISBN 0307472329

More on Marcel Proust

Twentieth century literature

More on biography

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

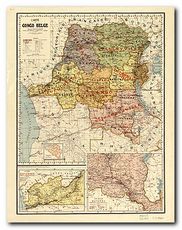

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

Marlow and his crew take the ailing Kurtz aboard their ship and depart. Kurtz is lodged in Marlow’s pilothouse and Marlow begins to see that Kurtz is every bit as grandiose as previously described. During this time, Kurtz gives Marlow a collection of papers and a photograph for safekeeping. Both had witnessed the Manager going through Kurtz’s belongings. The photograph is of a beautiful woman whom Marlow assumes is Kurtz’s love interest.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a good introduction to Conrad and criticism of the text. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the novella, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. The latter half of the book is given over to five extended critical readings of the text. These represent what are currently perceived as major schools of literary criticism – neo-Marxist, historicism, feminism, deconstructionist, and narratological.

The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes

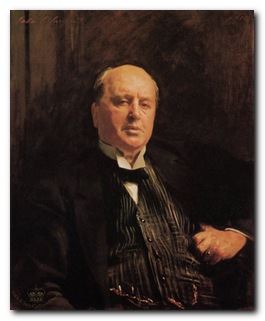

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All essays are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work.

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All essays are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work. Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Maisie Knew

What Maisie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors The Golden Bowl

The Golden Bowl