a chronicle of events, literature, and politics

1830. Death of George IV; William IV becomes King. Petitions to both Houses of Parliament on the abolition of slavery. William Huskisson, a former cabinet minister, is killed at the opening of the Liverpool – Manchester railway. Tennyson, Poems Chiefly Lyrical.

1831. Unsuccessful introduction of the Reform Bills. Darwin’s voyage on The Beagle.

1832. The First Reform Act extends the franchise to those owning property rated at 10 a year or more.

1833. Shaftesbury’s Factory Act limits hours of children’s employment. Slavery abolished in the British Empire. Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus.

1834. First colony established in South Australia. Tolpuddle martyrs exiled there. Emancipation of British West Indian slaves declared – though it takes four years for this declaration to be fulfilled. New Poor Law Commission establishes workhouses. Fire breaks out in the Palace of Westminster – much of the Houses of Parliament destroyed.

1835. Municipal Corporation Act gives votes for local government to men only.

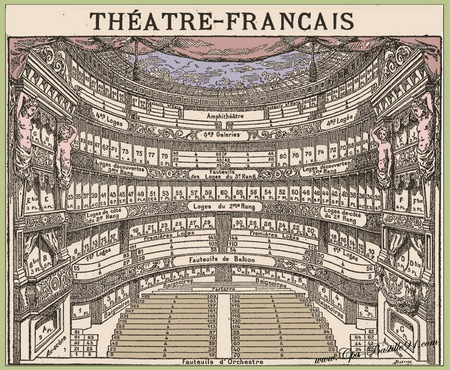

1836. Balzac begins La Comedie Humaine novel cycle. Pickwick Papers launches Dickens’s career. London University is formed. Newspaper tax reduced.

1837. Fox Talbot experiments with photographic prints. Queen Victoria ascends the throne. Dickens, Oliver Twist. Thomas Carlyle, The French Revolution.

1838. Chartist petitions published. Full emancipation of British West Indian slaves. The London to Birmingham railway is opened.

1839. Custody of Infants Act. (For the first time a woman living apart from her husband was able to apply for custody of children under seven.) Chartist riots. Daguerre patents photographic technique. Shelley, Poetical Works (posthumous)

1840. Beginning of a decade of considerable social and economic turbulence in England. Marriage of Victoria and Albert. Penny post established in UK. Start of a decade which saw a rise in so-called ‘condition of England novels’. Opium War – Chinese ports are besieged to force free passage of English narcotics. Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby.

1841. Governesses’ Benevolent Institute founded (see also 1829). Dickens, The Old Curiosity Shop. Thomas Carlyle, On Heroes and Hero-Worship.

1842. Mines Act forbids use of children and women in mines. New Chartist riots. Copyright Act extends the life of copyright to 42 years from publication or 7 years after the author’s death. Mudie establishes the circulating library. Browning, Dramatic Lyrics; Tennyson, Poems.

1843. Colonization of Africa includes Gambia, Natal, Basutoland. Dickens, Martin Chuzzlewit. Sara Ellis, The Wives of England: Their relative duties, domestic influence and social obligations. Ruskin, Modern Painters; Dickens, A Christmas Carol. Wordsworth appointed Poet

Laureate.

1844. Factory Act restricts working hours for women and children. First telegraph line, between Paddington and Slough. Engels, Condition of the Working Class in England. Royal Commission of Health in Towns. Co-Operative movement begun in Rochdale.

1845. Potato famine in Ireland. Boom in railway building speculation. Bronte sisters invest. Disraeli, Sybil, E.A. Poe, Tales of Mystery and Imagination. Franklin’s expedition to the Arctic to find ‘north west passage’.

1846. Repeal of the Corn Laws (legislation designed to protect the price of domestic grain from foreign imports). Famine in Ireland. Introduction of the ‘Marriage with a Deceased Wife’s Sister Bill’ (this is finally passed in 1907). C. Bronte, The Professor; George Eliot translates Strauss’s Life of Jesus; Ruskin, Modern Painters II.

1847. The first use of chloroform as an anaesthetic. Ten Hours Factory Act. Bronte sisters publish Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey in same year. Tennyson, The Princess. Thackery, Vanity Fair.

1848. Revolutions throughout Europe. Queen’s College for Women founded in London. Discovery of nuggets in California starts ‘The Gold Rush’. Introduction of a Public Health Act to try to tackle cholera. A. Bronte, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall; Elizabeth Gaskell, Mary Barton; Dickens, Dombey and Son; Marx and Engels, Communist Manifesto; Kingsley, Yeast. Dante Gabrielle Rosetti, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais form the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

1849. Bedford College for Women founded. Dickens, David Copperfield; C. Bronte, Shirley

1850. Pope Pius IX restores the Roman Catholic hierarchy in the UK – for the first time since the 16th century Catholics have a full hierarchy consistent with Catholic countries. The Public Libraries Act – first of a series of acts enabling local councils to provide free public libraries. Parliament imposes a sixty hour week. Death of Wordsworth. Tennyson becomes Poet Laureate; In Memoriam. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Sonnets from the Portuguese, Wordsworth, The Prelude, Dickens begins publishing Household Words. Thackeray, Pendennis.

1851. Great Exhibition in Hyde Park. Religious Census. Mrs Gaskell, Cranford, Harriet Taylor Mill, The Enfranchisement of Women. Matthew Arnold, Dover Beach. Ruskin, The Stones of Venice. Mayhew London Labour and the London Poor

1852. Dickens, Bleak House. Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Florence Nightingale, Cassandra. New Houses of Parliament open. First free public library opens in Manchester.

1853. Trollope, The Warden. C. Bronte, Villette

1854. Britain and France declare war against Russia to begin Crimean war. Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava. The British Medical Association is founded. Doctrine of the Immaculate Conception promulgated. Dickens, Hard Times, Gaskell, North and South. Coventry Patmore begins The Angel in the House (sequence of poems about female domestic responsibility).

1855. Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit. Repeal of stamp duty on newspapers; death of Charlotte Bronte. Elizabeth Gaskell, North and South; Robert Browning, Men and Women; Tennyson, Maud and Other Poems. Livingstone ‘discovers’ the Victoria Falls.

1856. Ruskin, On the Pathetic Fallacy; William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine.

1857. Indian ‘Mutiny’. Matrimonial Causes Act facilitates divorce for those who can afford it. The Obscene Publications Act is passed. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh. Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Bronte; Thomas Hughes, Tom Brown’s Schooldays; Anthony Trollope, Barchester Towers; Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary.

1858. ‘Big Ben’ is installed in the Houses of Parliament clock tower. India ‘transferred’ to the British Crown. Abolition of property qualification for MPs, enabling working-class men to stand.

1859. Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species; Eliot, Adam Bede; Samuel Smiles, Self-Help; J. S. Mill, On Liberty; George Meredith, The Ordeal of Richard Feverel; Tennyson, Idylls of the King. Samuel Smiles Self-Help. Mrs Beeton Book of Household Management

1860. Lenoir invents the first practical internal combustion engine.

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations; George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss; Wilkie Collins, The Woman In White; Ruskin, Unto this Last

1861. American civil war begins with eleven states breaking away to form southern confederacy. Emancipation of serfs in Russia. Italy united under King Victor Emmanuel. In England, daily weather forecasts begin. First horse-drawn trams are used in London. George Eliot, Silas Marner; Mrs Beeton, The Book of Household Management; Hans Christian Andersen, Fairytales

1862. George Eliot, Romola; George Meredith, Modern Love; Victor Hugo, Les Miserables

1863. Polish rising against Russian occupation. American Civil War – to 1865. Opening of the first underground railway in London. George Elder Hicks’ triptych of paintings entitled Women’s Mission are exhibited at the Royal Academy. Charles Kingsley The Water Babies

1864. Contagious Diseases Act. Formation in London of the International Working Men’s Movement (influenced by Marx); Matthew Arnold, ‘The Function of Criticism at the Present Time’

1865. Slavery abolished in United States. Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Lister develops antiseptic surgery. Cholera epidemic kills over 14,000. Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace; Ruskin, Sesame and Lilies. Lewis Carrol Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

© Roy Johnson 2009

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

Eugene Onegin

Eugene Onegin A Hero of Our Time

A Hero of Our Time Dead Souls

Dead Souls Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground

From the House of the Dead

From the House of the Dead Crime and Punishment

Crime and Punishment The Brothers Karamazov

The Brothers Karamazov  Anna Karennina

Anna Karennina War and Peace

War and Peace Fathers and Sons

Fathers and Sons