tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

His Father’s Son first appeared in Scribner’s Magazine issue number 45 for June 1909. The story was subsequently included in Edith Wharton’s collection of short fiction, Of Men and Ghosts published in 1910.

Old New Yotk

His Father’s Son – critical comments

From the late nineteenth century onwards there was a widely accepted convention that short (and even longer) stories ought to finish with something of a twist in the tale. In the most extreme cases, this became known as the ‘whiplash ending’. All the information provided by the story up to its conclusion was suddenly reversed or overturned – either by a sudden twist of fate, or by new information which had hitherto been concealed from the reader.

Modernist writers from Anton Chekhov, Virginia Woolf, and James Joyce onwards felt that this was a cheap and unsatisfactory literary device. They created narratives that would stand alone as satisfactory constructs without any element of surprise or dramatic revelation. But the device continued to be popular, particularly amongst writers of second rank or lower. Edith Wharton certainly resorts to this plot strategy from time to time in her stories, but in His Fathers Son she gives the surprise ending a double twist which goes some way to justifying its deployment.

Mason Grew is set up as a figure of mild pathos – the unfulfilled widower and man of commerce who is living out his youthful romantic aspirations via a son who appears to show no filial gratitude or appreciation. The doting patent is a common enough figure, both in life and in literature. And to the sad differences between them there is added the son’s higher social status, acquired at his father’s expense. The father is a manufacturer, and the son is a lawyer who mixes with wealthy New York socialites. How therefore to account for Ronald’s sensitive and artistic nature? The answer is – as Ronald himself thinks – in the long-hidden secret of his parentage. He is the love child of Fortuné Dolbrowski, whose letters to his mother Addie give proof of this idea.

That is twist number one – and there are hints enough in the story to encourage its credibility. But Wharton caps this revelation with a second more interesting twist. The correspondence with the great pianist was entirely the creation of Ronald’s father, Mason Grew, who seized a rare opportunity to exercise his own romanticism. Thus Ronald has inherited his romantic enthusiasms and disposition not from the pianist, but from his father, whose sensibility has been concealed beneath the trappings of manufacture and commerce.

His Father’s Son – study resources

![]() The New York Stories – New York Review Books – Amazon UK

The New York Stories – New York Review Books – Amazon UK

![]() The New York Stories – New York Review Books – Amazon US

The New York Stories – New York Review Books – Amazon US

![]() Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon UK

Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon UK

![]() Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon US

Edith Wharton Collected Stories – Norton Critical – Amazon US

![]() Tales of Men and Ghosts – Project Gutenberg

Tales of Men and Ghosts – Project Gutenberg

![]() A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

His Father’s Son – story synopsis

Part I. Following his wife’s death, Mason Grew moves from Connecticut to Brooklyn, so as to be near his son who is a New York lawyer. He tolerates Ronald’s lack of filial love by hiding behind a brash and over-confident exterior. As a practical businessman he nevertheless has romantic social ambitions which he lives out via Ronald, who is ashamed of his father’s lowly origins and success as a manufacturer of suspender buckles.

Part II. As Ronald has risen in society he has fulfilled his father’s own dreams of what might have been. Drew even secretly visits the theatre where he can observe his son mixing with wealthy socialites. When he receives a telegram from Ronald, his father thinks back over his humdrum past with his unexceptional wife Addie, and how they once went to a concert given by a famous pianist Dolbrowski.

Part III. Ronald is engaged to a rich girl Daisy and has come to tell his father that he can no longer accept his money because a cache of love letters from Dolbrowski to his mother have made him realise that he is the pianist’s natural son. Grew then puts Ronald straight by revealing that he wrote Addie’s letters to the pianist. He did it so that he could ‘breathe the same air’ as the great romantic, and this slender pleasure gave him the strength to continue in business for the sake of his son.

Principal characters

| Mason Grew | a practical businessman with romantic feelings |

| Ronald Grew | his son, a New York lawyer |

| Addie Grew | his dead wife |

| Fortuné Dolbrowski | a concert pianist |

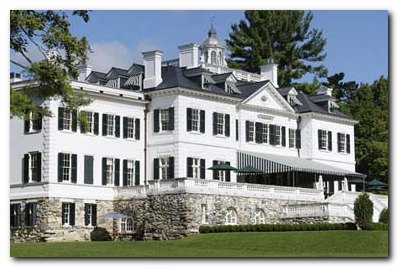

Edith Wharton’s 42-room house – The Mount

Further reading

Louis Auchincloss, Edith Wharton: A Woman of her Time, New York: Viking, 1971,

Elizabeth Ammons, Edith Wharton’s Argument with America, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1982, pp.222. ISBN: 0820305138

Janet Beer, Edith Wharton (Writers & Their Work), New York: Northcote House, 2001, pp.99, ISBN: 0746308981

Millicent Bell (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Edith Wharton, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp.232, ISBN: 0521485134

Alfred Bendixen and Annette Zilversmit (eds), Edith Wharton: New Critical Essays, New York: Garland, 1992, pp.329, ISBN: 0824078489

Eleanor Dwight, Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, ISBN: 0810927950

Gloria C. Erlich, The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton, California: University of California Press, 1992, pp.223, ISBN: 0520075838

Susan Goodman, Edith Wharton’s Women: Friends and Rivals, UPNE, 1990, pp.220, ISBN: 0874515246

Irving Howe, (ed), Edith Wharton: A collection of Critical Essays, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1986,

Jennie A. Kassanoff, Edith Wharton and the Politics of Race, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp.240, ISBN: 0521830893

Hermione Lee, Edith Wharton, London: Vintage, new edition 2008, pp.864, ISBN: 0099763516

R.W.B. Lewis, Edith Wharton: A Biography, New York: Harper and Rowe, 1975, pp.592, ISBN: 0880640200

James W. Tuttleton (ed), Edith Wharton: The Contemporary Reviews, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp.586, ISBN: 0521383196

Candace Waid, Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991,

Sarah Bird Wright, Edith Wharton A to Z: The Essential Reference to Her Life and Work, Fact on File, 1998, pp.352, ISBN: 0816034818

Cynthia Griffin Wolff, A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton, New York: Perseus Books, second edition 1994, pp.512, ISBN: 0201409186

Edith Wharton’s publications

Other works by Edith Wharton

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Edith Wharton – web links

Edith Wharton at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, tutorials on the shorter fiction, bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

The Short Stories of Edith Wharton

This is an old-fashioned but excellently detailed site listing the publication details of all Edith Wharton’s eighty-six short stories – with links to digital versions available free on line.

Edith Wharton at Gutenberg

Free eTexts of the major novels and collections of stories in a variety of digital formats – also includes travel writing and interior design.

Edith Wharton at Wikipedia

Full details of novels, stories, and travel writing, adaptations for television and the cinema, plus web links to related sites.

The Edith Wharton Society

Old but comprehensive collection of free eTexts of the major novels, stories, and travel writing, linking archives at University of Virginia and Washington State University.

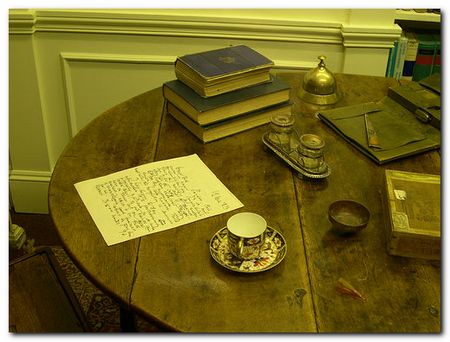

The Mount: Edith Wharton’s Home

Aggressively commercial site devoted to exploiting The Mount – the house and estate designed by Edith Wharton. Plan your wedding reception here.

Edith Wharton at Fantastic Fiction

A compilation which purports to be a complete bibliography, arranged as novels, collections, non-fiction, anthologies, short stories, letters, and commentaries – but is largely links to book-selling sites, which however contain some hidden gems.

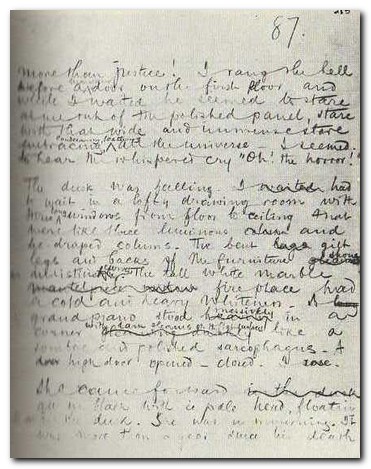

Wharton’s manuscripts

Archive of Wharton holdings at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© Roy Johnson 2013

Edith Wharton – short stories

More on Edith Wharton

More on short stories

find bargains at online bookshops

find bargains at online bookshops At the end of any scholarly writing (an essay, report, or dissertation) you should offer a list of any works you have consulted or from which you have quoted. This list is called a bibliography – literally, a list of books or sources.

At the end of any scholarly writing (an essay, report, or dissertation) you should offer a list of any works you have consulted or from which you have quoted. This list is called a bibliography – literally, a list of books or sources.

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.

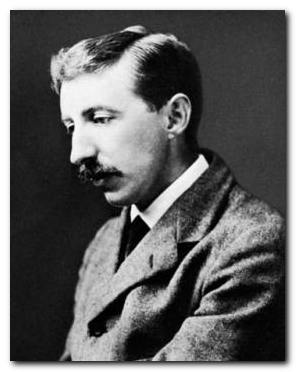

The Longest Journey

The Longest Journey A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness