tutorial, commentary, study resources, and plot summary

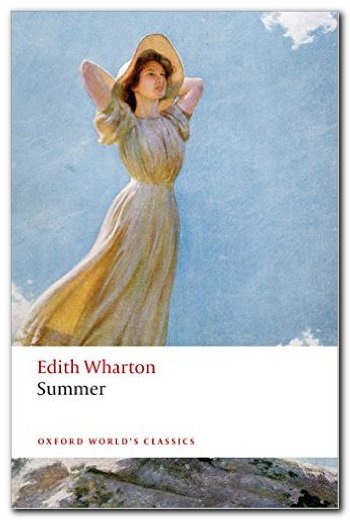

Summer was written in what Edith Wharton described as ‘a high pitch of creative joy’ in 1917, and was first published by D. Appleton later the same year. Wharton regarded it as a twin piece to her earlier novella Ethan Frome (1911) (and she even called it ‘my hot Ethan’). Like the earlier narrative the events of the story are set in a small, poor town in a remote part of New England.

Summer – critical commentary

Novella – or short novel?

It is often difficult to tell the difference between a short novel and a novella. The distinction cannot be measured in the number of words – and neither the novel nor the novella can easily be defined. But there is general agreement that a novella should be shorter than most novels – and that it should demonstrate a marked degree of unity of place, time, theme, action, atmosphere, and character. The novella also usually has some sort of unifying symbol(s) or metaphor(s). It usually compresses its themes into a shorter space by eliminating all superfluous incidents, having fewer characters, and concentrating on a central issue. Summer amply fulfils these requirements. It is approximately 50,000 words long – which is shorter than most full length novels.

Unity of place

Charity has been raised in the small rural town of North Dorner, and that is the location in which all the significant action takes place. Charity feels claustrophobically stifled by its intrusive small-minded parochialism and she years for a more sophisticated environment, even though she lacks the cultural knowledge or experience to define what that might be.

Her state of being is affected by two other locations which act as equal and opposite alternatives to her. When she visits the larger town of Nettleton with Harney she is very impressed by the shops, the soda-fountains, the hotels, and the restaurants which represent a more sophisticated level of existence. But the town also includes very negative elements. It is where her childhood friend has become more or less a prostitute, and the town also has a ‘doctor’ who acts as an abortionist. The town has attractions, but there appears to be a price to be paid for them for a girl such as Charity.

On the other hand, she knows she was born on the Mountain, and thinks that she can escape North Dormer by going back to her roots. But the Mountain hangs over her as a location of both her genetic origins and a source of social stigma. It is a place of poverty, lawlessness, and squalor – as she discovers when she goes back in search of her mother, who has died in abject poverty, apparently an alcoholic.

These are equally unacceptable alternatives, and it is mark of the coherence of the narrative that she opts for the realistic choice of staying in North Dormer with her new husband Mr Royall.

Unity of time

The story starts in the early summer and ends with the onset of autumn, and the events of the narrative are fairly continuous, with no leaps or breaks in the action. This is another sense in which the novella as a literary form is rather like the Greek ideal of classical tragedy – continuity of time, place, and unfolding of drama. Charity experiences youthful longing, her first taste of romantic love, initiation into sexual life, disillusionment, and ‘mature’ acceptance of reality – all within a few weeks.

Unity of characters

The entire narrative is focussed on three characters – Charity, Mr Royall, and Lucius Harney – who are locked in an emotional struggle. Charity wants a life larger than North Dormer seems to offer her, and she sees Harney as a potential for something more expansive and exciting. Her guardian Royall has his own designs on Charity, but he also has an over-riding concern for her ‘reputation’ and he sees Harney as an opportunistic interloper who wishes to take advantage of Charity whilst having his own future mapped out elsewhere – which turns out to be the case.

Harney comes into North Dormer as an outsider (he is a cousin of Mrs Hatchard) and is attracted to Charity. He establishes their secret ‘home’ together in the abandoned house, but he has no intention of pursuing their relationship beyond the temporary physical pleasure he enjoys with her. This is a crucial element in the cultural ambiance of small-town North Dormer – because Charity’s social reputation will be severely damaged if she is ‘tainted’ with the reputation of a sexual relationship with an outsider.

Her fate will be even worse if she has a child out of wedlock. This is why Royall’s intervention is the decisive factor. He offers her the protection of an unsullied reputation. She even has the outside chance to pass off the birth of her child as Royall’s rather than Harney’s, given that the conception and her marriage are so close together.

Unity of theme

What is the principal theme of Summer? It is a ‘coming of age’ story. Charity matures from a naive, romantic, and inexperienced girl to a young adult who has learned some difficult lessons and made realistic choices – all in the space of a few weeks. Between early summer and the onset of autumn she has rebelled against a parent figure, fallen in love, become sexually experienced, experienced emotional betrayal, and faced up to her problematic origins, before making a choice which represents a realistic compromise for her future.

Social movement

Charity’s story is also one of social aspiration. She has come from the desperate background of the social outlaws, drunks, and riff raff on the Mountain, and has a place in a small sleepy town in the middle of nowhere. Instinctively, she yearns for a more sophisticated and exciting milieu. But she has no education, no skills, and no social capital – except her good looks. These are never explicitly mentioned in the narrative, but since the two principal males find her attractive, it is reasonable to assume that they exist.

However, she knows that to trade on her sexual allure can easily lead to pregnancy and being trapped in an under-class of the socially stigmatised. She has the example of her childhood friend before her. So – eventually she marries into a very respectable middle class milieu – as the wife of a small town lawyer – which is quite an advance on her origins as the illegitimate child of an alcoholic

Loose ends

Royall’s desire to protect Charity and her reputation is a constant throughout the story, and is therefore credible as his motivation. But Wharton seems to fudge the conclusion somewhat. Royall makes no sexual overtures to Charity after they are married (although he has done so previously), and she does not reveal to him the fact that she is pregnant with Harney’s child. This would presumably be a grim emotional burden to Royall – though he might not be shocked by the news if the pregancy were to be revealed – though this is beyond the time frame of the novel.

There is also the issue of Royall’s adoption of Charity in the first place. He has sentenced her father for a serious crime (manslaughter) – but we are given no convincing reason why Royall should adopt the daughter at the criminal’s request – except, as the text suggests, as an act of charity, which provides an itonic link with her name.

In fact it is worth noting that her nominative identity is entirely shaped by Royall. She has been given her first name Charity by Royall and his wife ‘to commemorate Mr Royall’s disinterestedness in “bringing her down” [from the Mountain] and to keep alive in her a becoming sense of her dependence’. And her surname (until she marries him) is not Royall at all, but Hyatt, as the people on the Mountain know only too well.

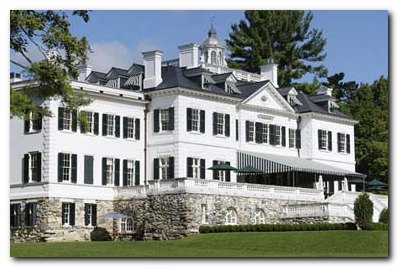

Edith Wharton’s 42-room house – The Mount

Summer – study resources

![]() Summer – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

Summer – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Summer – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

Summer – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() Summer – Bantam Classics – Amazon UK

Summer – Bantam Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Summer – Bantam Classics – Amazon US

Summer – Bantam Classics – Amazon US

![]() Summer – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

Summer – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() Summer – free eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

Summer – free eBook formats at Project Gutenberg

![]() A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

Summer – plot summary

Part I. Charity Royall is a young woman in North Dormer, a small country town in New England. She works in the local library, is bored, and yearns for a life with more sophistication and excitement. A young architect Lucius Harney comes to the library in search of local history.

Part II. Charity has been ‘brought down from the Mountain’ (a region of outlaws) by Mr Royall, a widower and lawyer who acts as her guardian. She feels sorry for him because he is so lonely, but he has made sexual advances to her – which she has scornfully rejected. She has taken up the job of part-time librarian in order to earn enough money to get away from the locality. When she makes this clear to Royall he proposes marriage – an offer she flatly refuses.

Part III. Charity feels in need of protection, so at her request Royall hires a woman to live in the house and do the cooking. Royall reproaches Charity for leaving the library early, and she threatens to leave.

Part IV. Lucius Harney returns to the library, whereupon Charity reproaches him for having criticised the condition of its books to the custodian Mrs Hatchard . He reassures her that he means no harm and suggests that he can improve ventilation of the building.

Part V. Some time later woodcutter Liff Hyatt from the Mountain interrupts her summer musings. She tells him that Harney wants to sketch one of the primitive mountain houses. She wonders if she and Hyatt are related and ponders the identity of her mother. She promises to take Harney up to the Mountain and reveals to him that she was born there, suddenly feeling a certain pride in the fact.

Part VI. Harney begins taking his meals in the Royall house, where they discuss the primitive and oppositional culture of the Mountain. Royall recounts visiting the mountain to retrieve a young girl from one of its drunken outlaws he has convicted. Charity overhears this account which turns out to be the story of her origins. She senses that Harney is interested in her but feels mortified by the cultural gulf that separates them. They visit some very poor people living in a primitive house near a swamp, which makes her feel ashamed of her origins.

Part VII. Next day Harney arrives with the clergyman Mr Miles to discuss the ventilation of the library. Charity is disappointed that Harney seems less interested in her than the day before. She goes out at night to his lodgings and watches him in secret. But she fears disturbing him in case he thinks it is a signal of sexual submission which she does not want to provoke, knowing what its consequences would be in a small town.

Part VIII. The following day Royall chastises her for having visited Harney’s house at night. He has seen the relationship between the two young people developing, and has suggested to Harney that he should leave (to protect Charity’s reputation). Royall once again proposes marriage to Charity. Harney arrives at the house to say an inconclusive goodbye – and next day sends her a message from a nearby village.

Part IX. Charity starts seeing Harney again. He is friendly, but no more. Two weeks later they go to a fourth of July celebration in a larger town. Charity is impressed by urban novelties. Harney buys her a jewelled brooch and takes her to a french restaurant for lunch.

Part X. They go on a boat trip around the local lake, then watch a spectacular firework display, during which they exchange passionate kisses. Charity sees a childhood friend who has become a tart in the company of her guardian Royall, with whom she has an angry confrontation.

Part XI. The following morning, filled with shame about the incident, she runs away from home, heading back to the Mountain. But she is overtaken by Harney, who takes her to an abandoned house in the countryside.

Part XII. Harney persuades her to return home, and they begin meeting each other every day in secret at the abandoned house. She becomes deeply enamoured of him.

Part XIII. At some local celebrations Mr Royall makes an impressive speech on parochial fidelity. But Charity sees Harney with another woman in the audience and realises that she cannot compete with sophistication.

Part XIV. Some days later she is waiting at the abandoned house when Royall appears. He asserts his right to keep her out of trouble. When Harney turns up Royall challenges them both with the question of marriage. Harney announces to Charity that he is going away but will marry her on his return.

Part XV. Harney leaves for New York and is non-commital about his return date. Charity hears that he is due to marry Annabel Balch. She writes to him urging him to fulfil his commitment. She also fears that she might be pregnant, and visits a doctor (an abortionist) in the nearby town for confirmation. She thinks the child will give her a strong claim on Haarney, but he writes confirming that he is going to marry Miss Balch. Charity feels that escaping and going back to the Mountain is her only option

Part XVI. Next morning she sets off with great difficulty for the Mountain, intending to seek out her mother. She is overtaken by Liff Hyatt and the clergyman Mr Miles who are also going to see her mother. When they arrive her mother has already died – in abject poverty and squalor. Her mother is buried, and Charity stays on, thinking to ‘rejoin her people’.

Part XVII. But during the night she realises that she does not want her own child growing up amongst primitive and degenerate people – and she sets off to walk back home again. She is rescued by Royall, who has driven out to look for her. He makes his third proposal of marriage.

Part XVIII. She feels a numb sense of relief at being protected by Royall. They are married in a simple ceremony, then retire to a hotel overlooking the same lake she visited with Harney. After retrieving her brooch from the abortionist (and being cheated by her) she writes to Harney saying she is married but will always remember him.

Summer – characters

| Mr Royall | a small town lawyer, a widower, and Charity’s guardian |

| Charity Royall | his young ward, a librarian (her real name is Hyatt) |

| Mrs Hatchard | custodian of the library |

| Lucius Harney | Mrs Hatchard’s cousin, a young architect from New York |

| Verena Marsh | Royall’s deaf cook |

| Liff Hyatt | a mountain woodcutter, a relative of Charity’s |

| Mr Miles | a clergyman |

| Dr Merkle | an unscrupulous abortionist |

Summer – further reading

![]() Louis Auchincloss, Edith Wharton: A Woman of her Time, New York: Viking, 1971,

Louis Auchincloss, Edith Wharton: A Woman of her Time, New York: Viking, 1971,

![]() Elizabeth Ammons, Edith Wharton’s Argument with America, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1982, pp.222. ISBN: 0820305138

Elizabeth Ammons, Edith Wharton’s Argument with America, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1982, pp.222. ISBN: 0820305138

![]() Janet Beer, Edith Wharton (Writers & Their Work), New York: Northcote House, 2001, pp.99, ISBN: 0746308981

Janet Beer, Edith Wharton (Writers & Their Work), New York: Northcote House, 2001, pp.99, ISBN: 0746308981

![]() Millicent Bell (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Edith Wharton, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp.232, ISBN: 0521485134

Millicent Bell (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Edith Wharton, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp.232, ISBN: 0521485134

![]() Alfred Bendixen and Annette Zilversmit (eds), Edith Wharton: New Critical Essays, New York: Garland, 1992, pp.329, ISBN: 0824078489

Alfred Bendixen and Annette Zilversmit (eds), Edith Wharton: New Critical Essays, New York: Garland, 1992, pp.329, ISBN: 0824078489

![]() Eleanor Dwight, Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, ISBN: 0810927950

Eleanor Dwight, Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994, ISBN: 0810927950

![]() Gloria C. Erlich, The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton, California: University of California Press, 1992, pp.223, ISBN: 0520075838

Gloria C. Erlich, The Sexual Education of Edith Wharton, California: University of California Press, 1992, pp.223, ISBN: 0520075838

![]() Susan Goodman, Edith Wharton’s Women: Friends and Rivals, UPNE, 1990, pp.220, ISBN: 0874515246

Susan Goodman, Edith Wharton’s Women: Friends and Rivals, UPNE, 1990, pp.220, ISBN: 0874515246

![]() Irving Howe, (ed), Edith Wharton: A collection of Critical Essays, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1986,

Irving Howe, (ed), Edith Wharton: A collection of Critical Essays, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1986,

![]() Jennie A. Kassanoff, Edith Wharton and the Politics of Race, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp.240, ISBN: 0521830893

Jennie A. Kassanoff, Edith Wharton and the Politics of Race, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp.240, ISBN: 0521830893

![]() Hermione Lee, Edith Wharton, London: Vintage, new edition 2008, pp.864, ISBN: 0099763516

Hermione Lee, Edith Wharton, London: Vintage, new edition 2008, pp.864, ISBN: 0099763516

![]() R.W.B. Lewis, Edith Wharton: A Biography, New York: Harper and Rowe, 1975, pp.592, ISBN: 0880640200

R.W.B. Lewis, Edith Wharton: A Biography, New York: Harper and Rowe, 1975, pp.592, ISBN: 0880640200

![]() James W. Tuttleton (ed), Edith Wharton: The Contemporary Reviews, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp.586, ISBN: 0521383196

James W. Tuttleton (ed), Edith Wharton: The Contemporary Reviews, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp.586, ISBN: 0521383196

![]() Candace Waid, Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991,

Candace Waid, Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld, London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991,

![]() Sarah Bird Wright, Edith Wharton A to Z: The Essential Reference to Her Life and Work, Fact on File, 1998, pp.352, ISBN: 0816034818

Sarah Bird Wright, Edith Wharton A to Z: The Essential Reference to Her Life and Work, Fact on File, 1998, pp.352, ISBN: 0816034818

![]() Cynthia Griffin Wolff, A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton, New York: Perseus Books, second edition 1994, pp.512, ISBN: 0201409186

Cynthia Griffin Wolff, A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton, New York: Perseus Books, second edition 1994, pp.512, ISBN: 0201409186

Other works by Edith Wharton

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition, social climbing, and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

The Custom of the Country (1913) is Edith Wharton’s satiric anatomy of American society in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the career of Undine Spragg, recently arrived in New York from the midwest and determined to conquer high society. Glamorous, selfish, mercenary and manipulative, her principal assets are her striking beauty, her tenacity, and her father’s money. With her sights set on an advantageous marriage, Undine pursues her schemes in a world of shifting values, where triumph is swiftly followed by disillusion. This is a study of modern ambition, social climbing, and materialism written a hundred years before its time.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of Lily Bart, who is beautiful, poor, and still unmarried at twenty-nine. In her search for a husband with money and position she betrays her own heart and sows the seeds of the tragedy that finally overwhelms her. The book is a disturbing analysis of the stifling limitations imposed upon women of Wharton’s generation. In telling the story of Lily Bart, who must marry to survive, Wharton recasts the age-old themes of family, marriage, and money in ways that transform the traditional novel of manners into an arresting modern document of cultural anthropology.

Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon US

Edith Wharton – web links

Edith Wharton at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, tutorials on the shorter fiction, bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

The Short Stories of Edith Wharton

This is an old-fashioned but excellently detailed site listing the publication details of all Edith Wharton’s eighty-six short stories – with links to digital versions available free on line.

Edith Wharton at Gutenberg

Free eTexts of the major novels and collections of stories in a variety of digital formats – also includes travel writing and interior design.

Edith Wharton at Wikipedia

Full details of novels, stories, and travel writing, adaptations for television and the cinema, plus web links to related sites.

The Edith Wharton Society

Old but comprehensive collection of free eTexts of the major novels, stories, and travel writing, linking archives at University of Virginia and Washington State University.

The Mount: Edith Wharton’s Home

Aggressively commercial site devoted to exploiting The Mount – the house and estate designed by Edith Wharton. Plan your wedding reception here.

Edith Wharton at Fantastic Fiction

A compilation which purports to be a complete bibliography, arranged as novels, collections, non-fiction, anthologies, short stories, letters, and commentaries – but is largely links to book-selling sites, which however contain some hidden gems.

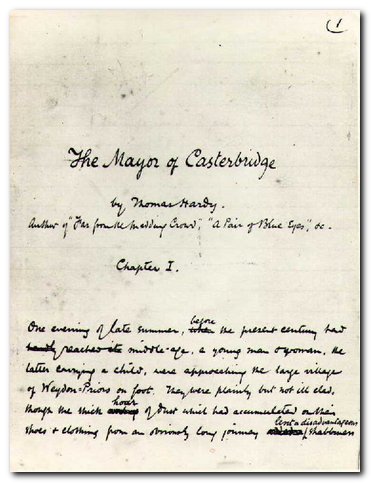

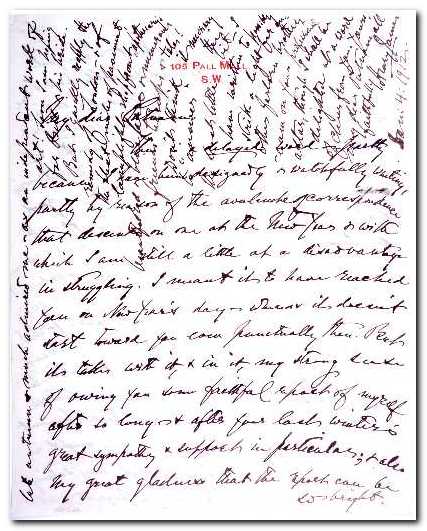

Edith Wharton’s manuscripts

Archive of Wharton holdings at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

© Roy Johnson 2015

More on Edith Wharton

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Jacob’s Room

Jacob’s Room Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf T.S.Eliot (Thomas Stearns) was born in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1888. His father was a successful businessman, and his mother wrote poems. From 1898 to 1905 he attended Smith Academy where he studied French, German, Latin, and Ancient Greek. At the age of fourteen he began to write poetry, heavily under the influence of The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam which enjoyed a vogue around that time. He published his first poem in the Smith Academy Record when he was fifteen.

T.S.Eliot (Thomas Stearns) was born in Saint Louis, Missouri in 1888. His father was a successful businessman, and his mother wrote poems. From 1898 to 1905 he attended Smith Academy where he studied French, German, Latin, and Ancient Greek. At the age of fourteen he began to write poetry, heavily under the influence of The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam which enjoyed a vogue around that time. He published his first poem in the Smith Academy Record when he was fifteen.

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy Far from the Madding Crowd

Far from the Madding Crowd The Return of the Native

The Return of the Native

The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

Archer visits Ellen (at her request) and is impressed by her bohemianism and her radical attitudes. He feels increasingly stifled by the expectations of his family and what he sees as the dull predictability of the married life ahead of him. Almost unknown to himself, he is attracted to Ellen and what she represents as a free spirit. Archer is asked by his law firm to handle the case Ellen wishes to bring against her husband for divorce. New York society prefers to avoid such a scandal, and Archer is successful in managing to persuade her against the action.

Archer visits Ellen (at her request) and is impressed by her bohemianism and her radical attitudes. He feels increasingly stifled by the expectations of his family and what he sees as the dull predictability of the married life ahead of him. Almost unknown to himself, he is attracted to Ellen and what she represents as a free spirit. Archer is asked by his law firm to handle the case Ellen wishes to bring against her husband for divorce. New York society prefers to avoid such a scandal, and Archer is successful in managing to persuade her against the action. The Reef

The Reef

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton