1920. Roger Fry, Vision and Design (a series of essays). Leonard Woolf writes leaders for The Nation. Omega workshop closes. First meeting of the Bloomsbury group Memoir Club. Desmond MacCarthy becomes literary editor of The New Statesman. E.M. Forster becomes literary editor of the London Daily Herald. Duncan Grant has his first one-man show in London. Carrington, Partridge, and Strachey visit Gerald Brenan in Spain.

1921. Virginia Woolf publishes her collection of experimental short stories, Monday or Tuesday, then falls ill and inactive for four months. Lytton Strachey, Queen Victoria. Dora Carrington marries Ralph Partridge, but continues to live with Lytton Strachey (who is in love with Ralph Partridge). E.M. Forster works in India as temporary secretary to Maharajah of Dewas. Leonard Woolf, Stories from the East and Socialism and Co-operation. John Maynard Keynes, A Treatise on Probability.

1922. Virginia Woolf publishes her first modernist novel, Jacob’s Room and starts her love affair with Vita Sackville West. Leonard Woolf is defeated as Labour candidate for the Combined University constituency. John Maynard Keynes, A Revision of the Treaty. Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant decorate Keynes’s rooms at King’s College, Cambridge. Lytton Strachey, Books and Characters: French and English. E.M. Forster, Alexandria: A History and a Guide. T.S. Eliot founder and editor of The Criterion. David Garnett, Lady into Fox. James Joyce’s, Ulysses published in Paris. Katherine Mansfield, The Garden Party.

1923. The Hogarth Press publishes T.S. Eliot’s, The Waste Land. John Maynard Keynes, A Tract on Monetary Reform: he becomes chairman of the board of The Nation and Atheneum, whilst Leonard Woolf becomes its literary editor. E.M. Forster, Pharos and Pharillon. Leonard and Virginia Woolf visit Gerald Brenan in Spain. Carrington begins an affair with Henrietta Bingham (one of Strachey’s former lovers).

1924. E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India widely acclaimed: (the composition of the novel was interrupted by the first world war – as was Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain). Virginia Woolf’s manifesto on modern literature, ‘Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown’. The Hogarth Press publishes Freud’s Collected Papers and begins the Psycho-Analytic Library. Lytton Strachey, Carrington, and Ralph Partridge move to Ham Spray House, Berkshire. The Woolfs (and the Hogarth Press) move to 52 Tavistock Square in Bloomsbury. First UK Labour government formed under Ramsey MacDonald (lasts nine months).

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

1925. Virginia Woolf publishes both The Common Reader and Mrs Dalloway, then is ill for three months. Leonard Woolf, Fear and Politics: A Debate at the Zoo. Lytton Strachey’s play The Son of Heaven is performed, and he lectures on Pope at Cambridge. John Maynard Keynes marries Lydia Lopokova, and takes a lease on a house at Tilton, near Charleston, which remains his country home.

1926. UK General Strike. Adrian Stephen and his wife Karin obtain bachelor of medicine degrees to become psycho-analysts. Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant decorate the house of Mr and Mrs St John Hutchinson. Roger Fry, Transformations. Ralph Partridge leaves Dora Carrington for Frances Marshall. Carrington begins an affair with Julia Strachey (Lytton Strachey’s sister). Vita Sackville-West wins Hawthornden Prize for her poem The Land.

1927. Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse. Clive Bell, Landmarks in Nineteenth Century Painting. Leonard Woolf, Essays on Literature, History, and Politics. E.M. Forster gives the Clark lectures at Cambridge, which are published as Aspect of the Novel. He also becomes a fellow of King’s College. Julian Bell enters King’s College as an undergraduate. Roger Fry becomes an honorary fellow of King’s College. His study Cezanne is published.

1928. Virginia Woolf, Orlando, a biographical ‘love note’ to Vita Sackville-West. Lytton Strachey, Elizabeth and Essex: A Tragic History. Desmond MacCarthy succeeds Edmund Gosse as senior literary critic of the Sunday Times. E.M. Forster, The Eternal Moment and Other Stories. Clive Bell, Civilization. Leonard Woolf, Imperialism and Civilization. Death of Thomas Hardy. First Oxford English Dictionary published. Carrington starts an affair with Bernard Penrose.

1929. Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, which was first delivered as a series of lectures at Cambridge. Roger Fry lectures at the Royal Academy. Collapse of New York Stock Exchange. Start of world economic depression. Second UK Labour government under Ramsay MacDonald.

1930. Leonard Woolf helps to found The Political Quarterly and becomes its first editor. Roger Fry, Henri Matisse. John Maynard Keynes, A Treatise on Money. Vanessa Bell has an exhibition of her paintings in London. Pipe-smoking lesbian feminist composer Ethyl Smyth falls in love with Virginia Woolf. Mass unemployment in UK. Death of D.H. Lawrence.

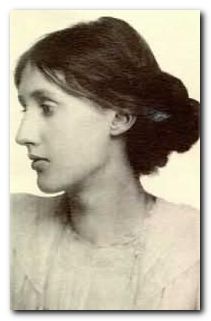

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. An attractive and very accessible introduction to the writer and her intellectual milieu.

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. An attractive and very accessible introduction to the writer and her intellectual milieu.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

1931. Virginia Woolf, The Waves. Leonard Woolf, After the Deluge. Lytton Strachey, Portraits in Miniature. John Maynard Keynes, Essays in Persuasion. John Lehmann joins the Hogarth Press for the first time. Resignation of UK Labour government, followed by formation of national coalition government.

1932. Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. Death of Lytton Strachey from stomach cancer, followed by suicide of Dora Carrington. Exhibition of paintings by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant in London. New Signatures published by the Hogarth Press. Roger Fry, Characteristics of French Art and The Arts of Painting and Sculpture. Hunger marches start in UK.

1933. Virginia Woolf, Flush, a biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s pet dog. Roger Fry appointed Slade professor of art at Cambridge and, Art History as an Academic Study. Clive Bell becomes art critic of The New Statesman and Nation. John Maynard Keynes, Essays in Biography.

1934. Clive Bell, Enjoying Pictures. E.M. Forster, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson. Death of Roger Fry, and publication of his Reflections on British Painting. Exhibition of Vanessa Bell’s paintings. Virginia Woolf publishes Walter Sickert: A Conversation.

1935. Private performance of Virginia Woolf’s unpublished play, ‘Freshwater: A Comedy in Three Acts’. John Maynard Keynes helps to establish the Arts Theatre in Cambridge. Leonard Woolf, Quack, Quack!.

1936. John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. E.M.Forster, Abinger Harvest, a collection of essays on literature and society. Virginia Woolf ill for two months. Death of George V in UK, followed by Edward VIII, who is forced to abdicate. Stalinist show trials in USSR. Julian Bell goes to participate in Spanish Civil War.

1937. Virginia Woolf, The Years. Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant both have exhibitions of their paintings. John Maynard Keynes seriously ill. Julian Bell killed in Spain.

The Art of Dora Carrington At the age of 38, Dora Carrington (1893-1932) committed suicide, unable to contemplate living without her companion, Lytton Strachey, who had died a few weeks before. The association with Lytton and his Bloomsbury friends, combined with her own modesty have tended to overshadow Carrington’s contribution to modern British painting. She hardly exhibited at all during her own lifetime. This book aims to redress the balance by looking at the immense range of her work: portraits, landscapes, glass paintings, letter illustrations and decorative work.

The Art of Dora Carrington At the age of 38, Dora Carrington (1893-1932) committed suicide, unable to contemplate living without her companion, Lytton Strachey, who had died a few weeks before. The association with Lytton and his Bloomsbury friends, combined with her own modesty have tended to overshadow Carrington’s contribution to modern British painting. She hardly exhibited at all during her own lifetime. This book aims to redress the balance by looking at the immense range of her work: portraits, landscapes, glass paintings, letter illustrations and decorative work.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

1938. Virginia Woolf, Three Guineas, her ‘sequel’ to A Room of One’s Own. John Lehmann joins the Hogarth Press for the second time as its general manager, buying out Virginia Woolf’s financial interest. Leonard Woolf appointed as member of the Civil Service Arbitration Tribunal, on which he sits for seventeen years. Germans occupy Austria. Chamberlain meets Hitler to make infamous Munich ‘agreement’ to prevent war.

1939. Leonard Woolf, After the Deluge, vol.II, The Barbarians at the Gate, and a play, The Hotel. The Woolfs and the Hogarth Press move to 37 Mecklenburgh Square. Fascists win Civil War in Spain. Stalin makes pact with Hitler. Germany invades Poland. Britain and France declare war on Germany. James Joyce, Finnegans Wake.

1940. Virginia Woolf, Roger Fry: A Biography. Hogarth Press bombed in Mecklenburgh Square, moved to Herfordshire. Angelica Bell’s 21st birthday: ‘the last Bloomsbury party’.

1941. Virginia Woolf, Between the Acts, then commits suicide by drowning herself in the River Ouse. Death of James Joyce.

1942. Virginia Woolf’s essays The Death of the Moth and Other Essays published posthumously. Angelica Bell, Duncan Grant’s daughter, marries David Garnett, her father’s former lover. John Maynard Keynes elevated to the peerage and takes seat as Liberal in the House of Lords. He was also the chairman of the Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (which becomes the Arts Council in 1945).

1943. Virginia Woolf’s A Haunted House and Other Short Stories published posthumously. Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, and Quentin Bell complete paintings for the parish church at Berwick, near Firle, Sussex.

1944. John Maynard Keynes is senior British representative at the Bretton Woods International Conference to plan for the aftermath of war.

1945. E.M. Forster elected honorary fellow at King’s College Cambridge, and takes up permanent residence there after his mother’s death. John Maynard Keynes goes to America to negotiate a loan for Britain. United Nations founded. Huge Labour victory in UK general election. Clement Atlee becomes prime minister.

1946. Death of John Maynard Keynes. Leonard Woolf sells John Lehmann’s interest in the Hogarth Press to Chatto and Windus. Vita Sackville-West made Companion of Honour for her services to literature.

1947. E.M. Forster, Collected Tales. Posthumous publication of Virginia Woolf’s The Moment and Other Essays.

1948. Death of Adrian Stephen. T.S. Eliot awarded Nobel prize for literature (for the UK).

1949. Posthumous publication of John Maynard Keynes’s Two Memoirs.

1950. Bertrand Russell awarded the Nobel prize for literature. Posthumous publication of Virginia Woolf’s The Captain’s DeathBed and Other Essays.

1951. E.M.Forster, Two Cheers for Democracy (essays) and writes the libretto for Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd. Desmond MacCarthy knighted.

1952. Death of Desmond MacCarthy. Death of George V. Accession of Queen Elizabeth II at 25.

1953. Leonard Woolf, Principia Politica (vol.III of After the Deluge and also publishes extracts from Virginia Woolf’s diaries as A Writer’s Diary. E.M. Forster, The Hill of Devi. Death of Stalin – and Prokofiev on same day. Nobel prize for literature – Winston Churchill (UK).

1956. Leonard Woolf publishes his correspondence with Lytton Strachey. Last meeting of the Memoir Club. Exhibition of paintings by Vanessa Bell.

The Bloomsbury Artists: Prints and Book DesignsThis volume catalogues the woodcuts, lithographs, etchings and other prints created by Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Roger Fry and Duncan Grant – with various colour and black and white reproductions. Of particular interest are the many book jackets designed for the Hogarth Press, the publishing company established by Leonard Woolf and Virginia Woolf. Also included are ephemera such as social invitations, trade cards, catalogue covers, and bookplates.

The Bloomsbury Artists: Prints and Book DesignsThis volume catalogues the woodcuts, lithographs, etchings and other prints created by Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington, Roger Fry and Duncan Grant – with various colour and black and white reproductions. Of particular interest are the many book jackets designed for the Hogarth Press, the publishing company established by Leonard Woolf and Virginia Woolf. Also included are ephemera such as social invitations, trade cards, catalogue covers, and bookplates.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

1957. Exhibition of paintings by Duncan Grant. Homosexuality decriminalised in UK.

1958. Posthumous publication of Virginia Woolf’s Granite and Rainbow: Essays. Duncan Grant decorates Russell Chantry, Lincoln Cathedral.

1959. Duncan Grant has retrospective exhibition of his paintings at the Tate Gallery.

1960. Leonard Woolf, Sowing: An Autobiography of the Years 1880-1904 and revisits Ceylon.

1961. Leonard Woolf, Growing: An Autobiography of the Years 1904-1911. Death of Vanessa Bell: memorial exhibition of her paintings.

1962. Leonard Woolf, Diaries in Ceylon 1904-1911. Death of Saxon Sydney-Turner. Death of Vita Sackville-West.

1964. Leonard Woolf, Beginning Again: An Autobiography of the Years 1911-1918. Death of Clive Bell. Vanessa Bell: A Memorial Exhibition of her Paintings by the Arts Council.

1965. Posthumous publication of Virginia Woolf’s Contemporary Writers. Death of T.S. Eliot.

1967. Leonard Woolf, Downhill All the Way: An Autobiography of the Years 1919-1939.

1969. Leonard Woolf, The Journey Not the Arrival Matters: An Autobiography of the Years 1939-1969. Portraits by Duncan Grant: An Arts Council exhibition. E.M. Forster awarded the Order of Merit. Death of Leonard Woolf.

1970. Death of E.M. Forster at the home of friends. Death of Bertrand Russell.

1971. Posthumous publication of E.M. Forster’s overtly homosexual novel, Maurice (written in 1913). Posthumous publication of Lytton Strachey by Himself: A Self Portrait.

1972. Publication of Roger Fry’s Letters 2 vols. Duncan Grant: exhibition of water colours and drawings. Posthumous publication of Lytton Strachey’s The Really Interesting Question and Other Papers. Posthumous publication of E.M. Forster’s The Life to Come and Other Stories.

1973. Posthumous publication of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway’s Party: A Short Story Sequence. Vanessa Bell: Paintings and Drawings, An Exhibition.

1987. Death and burial of Gerald Brenan in Malaga, Spain.

© Roy Johnson 2003

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

Almost without exception, the members of the Bloomsbury Group were opposed to the first world war. Their attitudes varied from outright pacifism through conscientious objection to quietism and a form of radical internationalism normally only found in figures such as Trotsky and Lenin. The origins of these attitudes – which were extremely unusual at the time – lay in the liberal, laissez-faire, free-thinking and non-religious beliefs which seemed to have spread from late nineteenth-century intellectuals such as

Almost without exception, the members of the Bloomsbury Group were opposed to the first world war. Their attitudes varied from outright pacifism through conscientious objection to quietism and a form of radical internationalism normally only found in figures such as Trotsky and Lenin. The origins of these attitudes – which were extremely unusual at the time – lay in the liberal, laissez-faire, free-thinking and non-religious beliefs which seemed to have spread from late nineteenth-century intellectuals such as

The painter

The painter

The Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group Bloomsbury Recalled

Bloomsbury Recalled Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900—1930

Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900—1930 A Bloomsbury Canvas

A Bloomsbury Canvas