tutorial, study guide, commentary, further reading

The Bolted Door first appeared in Scribner’s Magazine for March 1908 and was later included in the collection Tales of Men and Ghosts (1910). Edith Wharton was a commercially successful writer of short stories at this period, even though she felt she didn’t reach true maturity as an artist until the production of her novella Ethan Frome written in 1911.

The Bolted Door – commentary

This is a story that suffers from several serious weaknesses, but has one redeeming and unusual feature. The weaknesses are that it is based on a rather unconvincing idea; it is annoyingly repetitive; the first part of the story has little to do with the second; and the issue in question is technically unresolved.

The idea that someone has committed a murder but is unable to persuade others of his guilt is mildly amusing, but it is never seriously examined or brought to closure. Hubert Granice tells his story to a lawyer, then to a newspaper editor, and finally to someone who purports to be a detective. His tale becomes more complex and fanciful at each telling. In this way, the reader is led to believe that the murder is a product of his imagination. But he never reports to the police, and his account of events is never held up for comparison with any details of the original crime.

The first sections of the story deal with Granice’s failure as a playwright. He has invested time and money in his ambition to become a successful writer for the stage. Despite exploring various dramatic modes – ‘comedy, tragedy, prose and verse’ – he has failed in all of them. We can be forgiven for thinking that his urge to commit suicide is associated with this failure.

But the narrative then changes to focus on his attempts to confess to the murder of his cousin Joseph Lenman – all of which efforts are thwarted. After this point any mention of his theatrical ambition is forgotten – so there is no persuasive or thematic connection between these two elements of the plot.

Instead, the narrative is taken up with a very repetitive and long-winded series of ‘explanations’ which fail to convince a succession of people of his guilt. These are spun out in exhaustive detail, until he is finally persuaded to enter what we take to be a lunatic asylum as someone who is clearly deluded.

At this point his final confessor, the detective McCarren, reveals that he has solved the mystery of the original crime. He claims that Granice really did murder his cousin Joseph Lenman. However, McCarren produces no evidence in support of this assertion. There is no explanation of how he has uncovered the truth, nor is there any confirmation of Granice’s own account of the murder.

The story therefore concludes with producing a sense of irresolution. It becomes a ‘reversal of expectation’ narrative for which there is no justification.

Existentialism

However, there is a very interesting passage in the story which occurrs when Granice’s frustration is at its most intense. He is unable to persuade other people of his account of the murder, and as a consequence he feels trapped within his own anguished consciousness.

Edith Wharton expresses this state of mind in terms very similar to those used by Jean-Paul Sartre in his writing on existentialism which came forty years later – particularly in Nausea (1938). The protagonist of Sartre’s novel, Antoine Roquentin, experiences his own state of being with a feeling of repulsion. Granice’s anguish is expressed in very similar terms:

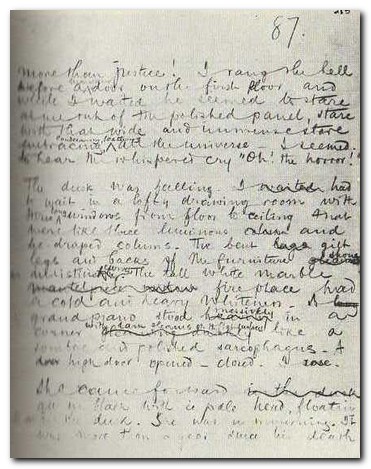

He was chained to life—a ‘prisoner of consciousness’ … he was visited by a sense of his fixed identity, of his irreducible, inexpugnable selfness, keener, more insidious, more unescapable, than any other sensation he had ever known … Often he woke from his brief snatches of sleep with the feeling that something material was clinging to him, was on his hands and face, and in his throat—and as his brain cleared he understood that it was the sense of his own loathed personality that stuck to him like some thick viscous substance.

In 1908 modern forms of existentialism were still some way off, so this counts as writing which was prescient, if not prophetic.

The Bolted Door – study resources

The New York Stories – NYRB – Amazon UK

The New York Stories – NYRB – Amazon US

Edith Wharton Stories 1891-1910 – Norton Critical – Amazon UK

Edith Wharton Stories 1891-1910 – Norton Critical – Amazon US

A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Introduction to Edith Wharton – Amazon UK

The Bolted Door – plot summary

I Hubert Granice is a failed playwright who entertains the idea of suicide because of his lack of success. He summons his friend the lawyer Ascham to whom he reveals that he committed a murder ten years previously.

II He reveals to Ascham the story of his rich elderly cousin Joseph Lenman whose hobby was growing melons. Granice poisoned Lenman by injecting cyanide into a melon, but Ascham does not believe his story.

III Granice repeats his story to Denver, the editor of a newspaper, with further details about how he arranged and carried out the murder. Denver challenges some of the details, and ultimately refuses to print the confession in his newspaper.

IV Granice takes his tale to Allonby the district attorney, who does nothing, but sends detective Hewson from his office to go over some of the details.

V Granice employs a reporter McCarren who checks on the car he claims to have used in the murder and a lock-up garage where it has been kept. However, all the evidence has disappeared in the ten years since the crime took place.

VI Granice discovers that detective Hewson is really a psychiatrist, who advises him to rest and give up smoking. In despair at his lack of progress, Granice decides to confide to a stranger, and on pestering a young girl in Washington Square, he is arrested by the police.

VII Granice is placed in what appears to be a mental asylum. He enjoys the peace and quiet, and begins writing long accounts of his ‘case’. When visited by McCarren and a friend, it is revealed that McCarren has discovered that Granice was telling the truth all along.

© Roy Johnson 2018

Edith Wharton – short stories

More on Edith Wharton

More on short stories

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

Washington Square

Washington Square

The Kingdom of This World

The Kingdom of This World The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps